Whiteshift by Eric Kaufmann (Book Review)

The end of the Cold War in the early 1990s ensured the United States would reach a level of international hegemony not seen since the time of Hadrian. Furthermore the rest of the rich world was aligned with this American world order (modulo some disagreements at the margin) and largely democratic, peaceful, and capitalist. What were seen as positive developments internationally in the form of increased economic and political liberalism in Africa, Asia, and South America under the intellectual aegis of the Washington Consensus also began in the 90s. In the First World progressive trends such as the increased openness towards towards homosexuality and growing female participation in the workforce and higher education appeared to augur a rosy social future. Even technological developments seemed to align with this general optimism with the creation of the Human Genome Project and the growth of the Internet. Though much pilloried now, Francis Fukuyama’s view that we had reached the end of history with liberal democracy permanently ascendant like Keats’ Happy Happy Boughs “that cannot shed [y]our leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;” does not seem retrospectively out of place. What halcyon days.[1]

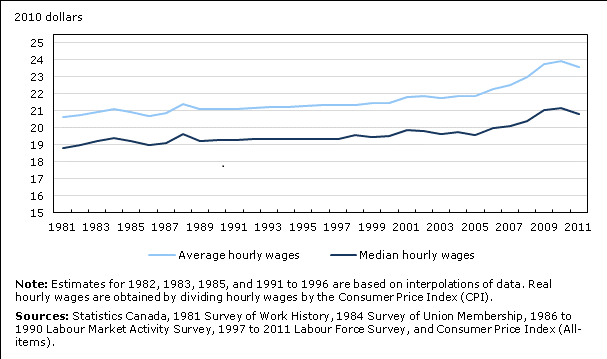

Thirty years later this trajectory seems to have at best stalled and at worst reversed. Disastrous foreign adventures in the Middle East coupled with a financial crisis on the scale of the Great Depression have taken the reputational gloss and confidence away from the Western world. Nor is this just a matter of perception. Within Western countries populist parties and politicians are in the ascendancy and economic conditions have stagnated for the majority of income groups. For example, in Canada real median wages increased by only 5% from 1981 to 2011 (see Figure 1 below), which corresponds to measly annual increase of 0.17% in contrast to real GDP growth per capita which grew 49%, implying an annual increase of 1.34%![2]

Figure 1: Real wages in Canada

Tensions between Western countries have been growing as well. The election of Donald Trump has caused (possibly) permanent damage to the Transatlantic alliances; hurting institutions like NATO and weakening the credibility of Article 5 (collective defense) against Russian aggression towards European member states. There has also been a gradual retreat of American support for countries in the Asia-Pacific region. For the first time since the end of WWII, Japan may not be supported by Seventh Fleet if China were, for example, to occupy the Senkaku Islands. The American military presence in South Korea can no longer be taken for granted and one could easily imagine Hong Kong and Taiwan being absorbed into China by military force if the United States could be placated by trade arrangements beneficial to domestic economic interests. The European Union, whose ultimate geopolitical purpose is to prevent Europe from bursting into the flames of war, has been permanently damaged by the poisoning of relations between the Mediterranean and Northern European countries after the Troika enforced austerity in exchange for bailouts, and Eastern European countries (as exemplified by the Visegrád Group) have refused to accept German-led refugee policy. Things are not going well for the Western world.[3]

The final source of tension within Western countries, and the focus of Eric Kauffman’s new book Whiteshift, is the increase of ethnic and cultural insecurity perceived by the white majorities of these countries. Trump’s electoral success was based on winning usually-Democratic states like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio by recruiting blue-collar and disaffected voters to his cause. While Trump’s policies will do little (and may even hurt) these same voters, he at least gave political attention to their concerns: de-industrialization and de-population, international trade, and the loss of cultural prestige these communities formerly had. And of course there is the issue of immigration. It’s become a common factoid that places with the fewest immigrants are the most hostile to immigration. The innuendo behind this statement is that opposition to immigration does not stem from legitimate concerns but rather imagined specters that would be exorcised if white communities were to actually spend some more time with their fellow Americans of a different background. The thesis of Kaufmann’s book is that while there may be some truth in the latter idea, it is wrong to say that cultural change is an illegitimate political consideration.[4]

Kaufmann’s views racial identity as an inevitable by-product of our psychology and need to construct real or imagined communities. Racial identity emerges whenever a group of people feel they have a shared history, language, or ideals. In countries like Brazil or Mexico, individuals identify as Caucasian or White, partly due to a lightness of skin, but also partly due to class, geography, and cultural attitudes. Kauffman suggests our behaviors are highly sensitive to the perceived racial makeup of the community. For example the book cites evidence that the ethnic distribution of one’s friend circle becomes increasingly biased towards the self-group as the share of this self-group goes down (white people’s friends are more likely to be white in multicultural cities like Toronto or Vancouver). In other words the propensity of the “token”-ethnic friend goes up when a community is increasingly homogeneous.

The institutional power of the liberal ideas in countries such as Sweden or Canada accounts for the powerful disjuncture between whites’ local behavior and their more cosmopolitan orientation towards immigration and national identity.

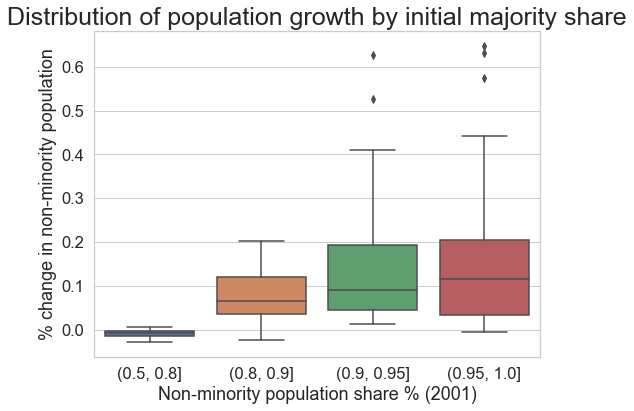

While few people would openly admit to selecting a community based on its ethnic makeup, one of the figures of the book implies that the historically “whitest” cities have tended to see the largest growth in the absolute number of non-minority individuals. I checked whether this was true for 51 major Canadian cities, and as Figure 2 below shows, cities that tended to have the highest non-minority share in 2001 saw larger growth rates in the non-minority population: i.e. “white” cities like Victoria saw large increases in the number of non-minorities that moved there whereas cities like Vancouver and Toronto have had very little growth in the total number of non-minorities[5].

Figure 2: Non-minority population growth (censuses 2001-2016)

While individuals in Western countries may act in a race conscious way through their choice of friends, romantic partners, and neighborhood, social taboos ensure that the politics of these countries restricts which topics can and cannot be discussed. Though the exact delineation of these boundaries varies by county there are general principles: issues of a “civic nature” are up for debate (crime, terrorism, public services, etc) whereas cultural anxieties are not. While anti-racism taboos are a legitimate response to the immense amount of misery that racism has caused to minorities in Western countries’ recent and extended history, Kaufmann believes that some of the limits imposed on political discourse leads unintended side-effects which actually makes life worse for minorities. His view is well-summarized in the following paragraph:

Should we push for maximal or minimal anti-racism norms? When anti-racism norms retreat, opposition to immigration or backing for populist-right parties may rise because voting for such parties or holding anti-immigration sentiments is viewed as more acceptable On the other hand, suppressing the expression of majority ethnic sentiment is a risky strategy: if the anti-racist consensus begins to fray, memories of past suppression of grievances turns into a force multiplier for the radical right. Meanwhile, those forced to sublimate ethnic concerns have to construct secondary arguments about pressure on public services which leads to policy distortions such as denying services to immigrants. This damages the lives of immigrants without addressing majority grievances. Permitting freer expression of the majority group’s sense of cultural loss … is, in the long run, probably less dangerous than repressing them.

And:

Paradoxically, it became more acceptable to complain about immigrant crime, welfare dependency, terrorism or wage competition than to voice a sense of loss and anxiety about the decline of one’s group or a white-Christian tradition of nationhood. It’s more politically correct to worry about Islam’s challenge to liberalism and East European ‘cheap labour’ in Britain than it is to say you are attached to being a white Brit and fear cultural loss. The means left-modernism has placed us in a situation where expressing racism is more acceptable than articulating racial self-interest. This is perverse and twists political reasoning to produce counterproductive outcomes like denying welfare to immigrants, preventing them form working, and in America, prompting the electorate to vote to cut spending on schools, roads, and hospitals. I’d argue that sublimated white-majority cultural expression also underlies rising Islamophobia, Euroskepticism, populism, polarization and declining trust in liberal democratic institutions.

Throughout the book Kauffman does a good job at showing the unique trajectories different countries have had in the development of white identity movements and associated policy concerns. While the nativist politics of Western countries have evolved endogenously (largely since the 1990s), Whiteshift details the longer intellectual tradition of multiculturalism which dates back to the early anti-WASP sentiments of bohemiams and artists at the turn of the century. How the balance between the pro-multicultural sentiments held (largely) by the elites of different countries has competed with the more reactionary world-views of the general population makes for some interesting case studies. During a by-election in 2014 the UK politician Emily Thornberry tweeted an image of a white van covered in English flags with the caption “Image from #Rochester” – implying that the city was a cultural backwater full of jingoistic and unsophisticated locals (Thornberry holds a seat in downtown London). She was roundly criticized for her tweet and forced to resign her role in the Shadow cabinet.

Showing a house covered in English flags, with a white van parked out front, Thornberry’s picture represented everything middle-class liberals derided about the patriotic white working class. The flying of the English flag, the Cross of St George, used to be associated almost exclusively with the far right and hooliganism. While this began to change when fans of England’s national football team embraced the symbol in 1996, the flying of the flag outside periods of international football rivalry is still viewed by middle-class liberals as racist or distasteful…..

While the Labour party was founded on working class and union votes, over the last 30 years traditionally center-left parties like Labour, the Liberal Party in Canada, and the Democratic Party in the United States have made a move towards the center – part of political movement dubbed the Third Way which began in the 1990s. The result of this political realignment has led, astonishingly, to there being no actual class difference between Labour and Tory voters in the UK.[6] However the Labour party still remains openly wedded to supporting “working families” and the loss of these voters from their electoral coalition is seen as a sign of failure. Comments perceived as snobbish and alienating (as exemplified by Thornberry) are seen as own-goals and barriers to electoral majorities for the Labour party in the UK. In a country like Canada where explicit class differences are not embodied in the two largest political parties, the consequences of Thornberry-like gaffes are less severe:

The contrast with Canada, where political correctness retains its exclusive focus on minorities rather than the white working class, is stark. In 2001, Hedy Fry, the Trinidad-born Minister of State for Multiculturalism in the Liberal government, said on the floor of the House of Commons: ‘Mr Speaker, we can just to go Prince George, in British Columbia, where crosses are being burned on lawns as we speak.’ The comment, a figment of Fry’s imagination, effectively smeared a British Columbian pulp-and-paper town as a hotbed of racism… The fact that Prince George is part of the Conservatives’ interior western heartland, and, like most rural Canadian communities, is predominantly white-working class, was enough for Fry to brand it a racist backwater. Though compelled to apologize she didn’t resign and received light treatment because in Canada’s public discover the white working class are considered fair game. Had this happened in Britain in 2014 (‘crosses burning in Sunderland’), her political career would have been over. Likewise had Fry called for sharply reduced immigration, her political life in Canada would have juddered to a halt. This illustrates the different political norms prevailing in the two countries. In Britain in the 2000s, immigration skepticism and white working-class identity politics had gained significant yardage against norms seeking to repress majority ethnic sentiment. In Canada by contrast, anything that could be construed as pro-white lay beyond the racist pale.

While almost all left-wing parties in Western countries have so far refused to countenance coalitions with populist anti-immigrant parties, the temptation to do so in order to both win back blue collar voters and form majority governments may eventually win out. A fascinating case in point is the 2017 New Zealand election where Jacinda Arden’s Labour party went into coalition with the anti-immigrant New Zealand First party by promising to reduce annual net immigration flows from 72K to 40K (Arden’s party did not even win the plurality of seats). It is interesting to note that many of the anti-immigrant populist parties which are currently experiencing electoral success were started (or detoxified) in the 1980-90s (New Zealand First, UKIP, One Nation, FPO, Sweden Democrats). Like a dormant virus they have started to hijack the political machinery of democracy and are rapidly proliferating. Political issues around identity, religion, and multiculturalism are beginning to consume more and more of the political oxygen in Europe.

Calls to curtail Muslim liberties – banning burqas, restricting the wearing of hijabs in state schools, outlawing the construction of minarets or new mosques - entered the political lexicon in Western Europe in the 2000s. Pim Fortuyn and Geert Wilders in the Netherlands and Marine Le Pen in France were at the front end of the new anti-Islamic politics. In 2004 France clamped down on the wearing of hijabs in state schools. From 2011 France and Belgium baned the burqa, followed by partials bans in the Netherlands in 2015, Switzerland in 2016, and the Canadian province of Quebec in 2017.

However there are some topics that even right-wing parties will not touch. For example the recently-elected CAQ party in Quebec campaigned on expelling immigrants if they failed a “values” test. A party spokesperson defended this policy by saying “Our goal is to ensure when they get settled here permanently is to make sure they speak French, adhere to our values and want to work”. Yet the CAQ was also proposing a simultaneous reduction in language requirements if immigrants could prove they had needed technical skills. The message the CAQ wanted to say but was political unable to due to existing taboos was “Our goal is to ensure that the cultural composition of Quebec remains largely the same and that immigration does not alter this balance”. While the idea of dog-whistle politics is well-known, Kauffman’s thesis provides a more clear-sighted lens by which to view these comments: a large segment of the voting population wants to preserve the share of the population with a white cultural identity and politicians will offer policies which directly, or in proxy, address this concern. There are some countries in which the language of cultural preservation has no obfuscation however.

The inner sanctum … consists of anti-racist taboos against expressions of white identity and white or Christian nationalism. This too has been breached, though only in Eastern Europe, where discursive restrictions arguable never existed but failed to surface because of the paucity of immigrants. The stand against accepting Muslim refugees taken by the Visegrad countries – Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland – during the 2015 Migration Crisis, drew a clear line in the sand. ‘Islam has no place in Slovakia’, said the country’s leftist Prime Minister, Robert Fico. ‘Migrants change the character of our country. We do not want the character of this country to change.’ In March 2017, the Hungrarian Prime Minister, Victor Orban, called migration a ‘poison’, extolled the benefits of ‘ethnic homogeneity’ and urged his audience to ‘keep Europe Christian’. Anti-racist taboos pertaining to immigration had never taken root in these societies, bot open ethnic nationalism of this kind from political leaders in the European public sphere had been rare.

While one hopes that most countries will avoid the worst populist excesses seen in Eastern Europe, a sure inevitability is a changing ethnic mix in all Western countries due to intermarriage and immigration. This is the second meaning of Whiteshift in the book: how will “white” identity change in mixed-race societies? Will countries like Canada go the way of genetic admixture like Saint Helena or remain ethnically stratified like South Africa? Kauffman suggests neither. White identity will be maintained through a cultural heredity rather than SNPs – similar to the way multi-ethnic countries like Brazil or Mexico still maintain racial distinctions.

Looking slightly more Caucasian could be sufficient, but this may provide only an approximate clue to identity - just as having a surname like O’Neill is only an approximate indicator that a person identifies as Irish Catholic. Terence O’Neill is a famous British-protestant and an Italian-American could also be named O’Neill. Like the Italian O’Neill some who identify as white may initially be miscategorized as black until people get to know their name, how they speak and more about their outlook. Over time, people get used to the idea that appearance is only a first approximation of identity, not a requirement for membership. Lifestyle of naming practices, as in Brazil, may offer additional clues as to whatever someone who appears non-white identifies as white. Having said this, ethnic groups require cultural markers to distinguish themselves from others. When race no longer distinguishes all members of white majorities from other groups, it may be the cultural styles, speech, folkways or naming practices – whether first names or surnames – take over the marking role. A person who exceeds a critical mass of cultural markers is accepted as a member.

One issue with this book that I found annoying was the author’s constant need to reference small sample size studies carried out on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to “demonstrate” some claim. In the era of the reproducibility crisis these type of noisy measurements are unconvincing forms of evidence. Whiteshift could be criticized as a one-sided view of recent political history seen only through the lens of immigration and the impacts of globalization on white-majority countries. However I think this is actually a strength of the book as it keeps the focus on a single political thesis to which the author is well versed – similar to the way Piketty’s Capital focuses on inequality. While sometimes bordering on the tedious (like Capital!), Kauffman’s 500 page treatise on the ethnically-centered political dynamics of Western countries is an essential read for understanding the emerging political landscape in a post-Brexit/Trump world.

-

The 1990s must have been a simpler era when one considers that the entire political and media establishment of the United States could be consumed by a presidential sex scandal whose impeachment proceedings could be based on the forensic evidence of a blue dress. ↩

-

Source: FRED Economic Data. ↩

-

In contrast things are actually going quite well for the world as a whole. Global income inequality is falling since the income gap between between countries is falling faster than income inequality is rising within countries, and almost every measure of human flourishing has shown marked improvements over every decade in the last thirty years including the number of people living in extreme poverty, literacy and child mortality. ↩

-

From a statistical perspective this factoid is also problematic due to a selection bias: individuals most comfortable living in a racially diverse metropolis are more likely to live there, whereas individuals who prefer more homogeneous communities may have already moved for this very reason. ↩

-

Data based on 51 cities three subsequent censuses: 2006, 2011, and 2016 (Abbotsford, Barrie, Brandon, Calgary, Camrose, Charlottetown, Chilliwack, Cobourg, Collingwood, Cranbrook, Drummondville, Duncan, Edmonton, Fort St. John, Fredericton, Granby, Guelph, Halifax, Hamilton, Joliette, Kamloops, Kelowna, Kentville, Kingston, Kitchener, Lethbridge, Lloydminster, London, Medicine Hat, Moncton, Montreal, Oshawa, Ottawa - Gatineau, Peterborough, Quebec, Red Deer, Sarnia, Saskatoon, Sherbrooke, St. Catharines - Niagara, Stratford, Summerside, Swift Current, Tillsonburg, Toronto, Truro, Vancouver, Victoria, Winnipeg, Wood Buffalo, Woodstock). ↩

-

Although Labour voters are still more likely to self-identify as working class. ↩