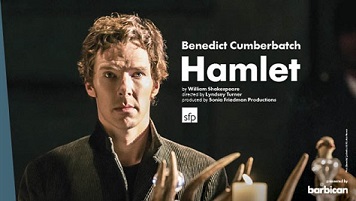

Hamlet at the Barbican (Play Review)

The bar was always going to be high for Lyndsey Turner’s recent production of Hamlet at the Barbican this year. In addition to the responsibility of directing a play by one of England’s three greatest men,[1] and one of the Bard’s finest works,[2] she had to provide the space in which Benedict Cumberbatch would play a role that all great rising and aspiring male actors must do whilst not letting his celebrity and central character drown out the rest of the cast. Tricky indeed.

We start the play with Bumblesnuff whimpering in his bedroom, listening to Nat King Cole’s “Nature Boy”, instantly alerting us that we are not going to be finding ourselves in the Saxo Grammiticus’ 10th century Viking-era Hamlet. Instead we are in what appears to be some sort of militarized country home, a mix of Chequers and the Pentagon’s war room, because as is oft an issue in Scandinavia, a rebellious prince (Fortinbras) “Hath in the skirts of Norway, … / Sharked up a list of lawless resolutes” and is threatening the national security of Denmark. This first line delivered by Hamlet (“Who’s there?”) also alerts us to the fact that the order of the play and lines are not going to be followed identically to the script.[3] So who is there? Why, Horatio (played by Leo Bill) decked out in a flannel shirt and hipster decals. Not only are we not in Kansas, we are apparently in an anachronistic Elsinore.

After establishing’s Hamlet serious lack of mirth, we move to a royal dinner, where Claudius introduces the audience to he and Gertrude’s “o’er hasty” marriage, and thanks the political insiders for their support in usurping the crown.[4] Cirian Hinds acting of Cladius strikes me as one of the most balanced deliveries throughout the play, with a mix of anxiety but also resolute determination as we are wont to expect of usurpers who do not see floating daggers “breech’d with gore”. This scene also lets us appreciate the amount of work that went into the stage design. We see scowling portraits of former military rulers of Denmark and Gothic amounts of dusty leather bound books and deer’s antlers. Elsinore is a macabre place, if not a little beautiful. As the dinner winds to an end, Hamlet jumps on the table and delivers his “too too sullied flesh” speech whilst all the other characters move in slow motion. I quite enjoyed the effects. We also get to see Cumberbuff’s fantastic and commanding acting abilities. While some reviews found him ‘too in control’ of his dialogues, rather than suffering from a sufficient amount of his “sore distraction”, I found this to a feature not a bug. Hamlet has delighted over-privileged educated white males who have read him throughout the centuries due to his mix of cunning, ennui, and irresolution that I think our tribe is well known for. We do not want Hamlet’s mascara running as he deals with his feelings. We want insightful revelations about his petulant and childish emotions presented through a pseudo-intellectual veneer.

One of the most important relationships any director ofHamlet must take is to make the relationship between Hamlet and Ophelia realistic and therefore their future interactions believable. Ms. Turner’s choice to give Ophelia a Facebook relationship status of “it’s complicated” and therefore seriously “just-casual” can be done, but then how we do explain Hamlet’s later outbursts at Sian Brooke’s character? Additionally, because the audience gets the sense that Hamlet has been poking around her lady’s closet for quite some time now, Ophelia’s declaration to her father that Hamlet “… hath … of late made many tenders” and “… importun’d me in … in honorable fashion” is a stretch. While Ms. Brooke’s acting was delightful with her skittish and trembling displays of the “poor wretch”, I do not feel it was directed well to work with the existing relationships or fit into the larger narrative.

It has been said that Hamlet is a play about son’s relationships with their fathers: Hamlet/Denmark, Laerters/Polonious, and Fortinbras/Norway. Ms. Turner’s production certainly does not emphasize this angle. While we cannot expect to be given a large psychological insight into Fortinbras due to his paucity of lines, we do know that his “mettle hot and full” is in part to avenge some aspect of his lineal rights. So when it comes to the characters we do see, how are their paternal relationships played out? For Laertres, we do not get the sense that as he departs for France he is particularly pleased to see his father.[5] And as Polonius delivers his sermon about how to deal with men of the “best rank and station” in France, his does so in the most rote of ways, perfunctory rather than charming from being overweening.[6] This is especially troubling because as Kobna Holdbrook-Smith’s character returns guns-toting in Act IV, Scene V, his demands for “Where is my father!” come off as mawkish given the incredulity of it.

Both Orson Welles and Peter O’Toole agree that the hardest role to play in Hamlet is the Ghost; which is why it was suggested that the Bard choose the role for himself. In what will be my most scathing lines of this review, I found the presentation of the Ghost and his relationship with his son the weakest and most profoundly disappointing part of the play. First, the recently-deceased King comes across as both frail and crotchety.[7] Why this is so troubling for the play is that Hamlet throughout speaks of his father the king as a “man” and an “Hyperion”, all of which demands that this “[s]o excellent a king” come across as a strong and powerful blue blood in contrast to the “satyr” of his wicked brother. At no point in any of Hamlet’s interactions with the Scotch-accented Ghost do we feel that Bumblefire would feel the slightest filial woe in the absence of his father.

As we move into the last half of the play, Elsinore manor is hit with a bomb and bits of ash are blown all over the floor. While it seems unlikely that the chief military headquarters of a nation could be bombed and not fixed, I am tempted to interpret the grime as moral decay coming from the unnatural and foul murder which has occurred in Denmark. Laertes bursts in guns akimbo and demands to know where his father is. Smooth-talking Claudius disarms the situation and convinces Polonius’ son to save his wrath for the true murderer of his father. Again, the passion that the actor shows for the murdered eminence grise does not feel appropriate somehow.

Nevertheless, at the end of the play as Hipster-Horatio wishes his “sweet prince” a good night into the “undiscovered country” in the after-math of the ‘fencing masacre’, the audience finds itself overall satisfied with the performance. While there has been some abridgement of the text, the snug three hour length with intermission feels like the right duration. Even though the relationships between the fathers and sons of the play is wanting, due to Beeswax Cauliblum’s incredibly strong performance, I feel that this Thespian’s current popularity is warranted by his skill as an actor. I leave the performance incredibly excited for 2016.

Footnotes

-

I would consider the three greatest Englishmen ever to have lived to be Shakespeare, Newton, and Darwin (given in chronological order rather than that of importance). ↩

-

Several articles and books I have read recently have suggested that King Lear is Shakespeare’s greatest work. Maybe this acclamation will appear more sensible to me when I am older, but in my young and foolish years I cannot see the merit in such a ranking. Hamlet’s words are the closest to a grab-bag of meditations in an emergency that any of Shakespeare’s characters give us. To me the play is an endless fountain of immortal drink, as Keats might have put it. ↩

-

In the original text, Bernado (a guard) delivers these lines to his fellow watchmen. ↩

-

A great deal of ink has been spilled over analyzing the political system of Elsinore, and to what extent machinations allowed Claudius to assume the throne. Whilst there are references to “elections” in the play, and no direct mention of primogeniture, it almost seems certain that constitutional preference would be for the recently departed King’s son to take up the throne. ↩

-

While of course all the characters find Polonius to be slightly ridiculous, one imagines that Laertes would still find his father’s antics to be amusing, if at least in an ‘eye-roll’ way. ↩

-

At slightly less than 3 hours with an intermission, this version of Hamlet had to see some truncation of lines and scenes. Unfortunately that included Polonius’ sound advice to “neither a debtor not a lender be / for loan oft loses both itself and friend / and borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.” As an economist, I was deeply saddening at this budget cut. ↩

-

Admittedly one would not come across as happy after that “wicked incestuous beast” poured poison in your ear and stole your kingdom, wife, etc., but crotchety is different from malice, the former being more silly than serious. ↩