Economics - To Beta or Not to Beta (Pensée)

Introduction

What is economics? Clearly it is what economists do. But despite this unsatisfying albeit amusing quip there is little coherence in the public or professional mind as to what exactly our métier does with all its spare time. Some would say that we are busy becoming rich or dominating the social sciences but I think we will need to look to Keynes[1] for inspiration.

If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people, on a level with dentists, that would be splendid!

To understand why this quote is so poignant as to the collective psyche of our profession, the reader needs to understand two powerful ideas that economists have in viewing their role within the world. The first idea is that economics is descriptive rather than prescriptive. In introductory economics textbooks the terms normative and positive are used. The former being what ought to be, and the latter being what is.[2] What dentists are fantastic at being is ‘positive’. Despite the somewhat preachy posters that accost you for not flossing enough in the waiting room, dentistry is as apolitical a discipline as we can have in the 21st century. The second is that economists aspire to be technicians. If dentists use engineering to rid the teeth of cavities, economists use econometrics to drill out bits of deadweight loss.

But as Jack points out to Algernon in The Importance of Being Earnest:

My dear Algy, you talk exactly as if you were a dentist. It is very vulgar to talk like a dentist when one isn’t a dentist. It produces a false impression.

I also believe we should be careful to describe our field as something with which it is not. However, the political incentives are clear enough. A “science” does not allow for various opinions in the way that, say, politics does. To disagree with a scientific theory, one has to make a case using the field’s argot and premises. This ability to exclude other points of view from outside the specialization is no doubt useful for astrophysics, but serves as a way to extend the power of economics into public policy. The more economics is able to reduce publicly-acceptable opinions to only technocratic experts, the more power and prestige these experts can garner.

A Brief History of Time the Infinite-Horizon Representative Agent Model

Before WWII economics was scarcely recognizable to its modern incarnation. While Newton would likely get into graduate mathematics program today, it is almost certainly the case that Adam Smith would not get into an economics program. As Yanis Varoufakis put it in 2013 (emphasis mine),

Today, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Friedrich Hayek, even John Maynard Keynes, would never get a job at Harvard University’s Economics Department. Never. Under no circumstances… It’s like Jesus Christ not being allowed in Church.

The first signs of economics changing its public persona actually began in WWI.[3] One can read an interesting essay by Irving Fisher written in early 1919 discussing economists in public service. It is worth quoting in whole:

It therefore becomes each of us, as we pause of the threshold of a possible “new world,” to consider what are the new opportunities and what the new duties which lie before us. That new world of which are speaking is still unbuilt. Is it to build itself unplanned, or is it to have architects? And are we to be numbered among the architects? These are undoubtedly some of the thoughts and hopes and fears that stir us today.

Since the onset of the post-War international order led by the United States, the discipline of economics had been granted an exorbitant privilege. Just as individuals with a health science background make up the membership of the National Institutes of Health, the major global financial institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, or OECD are all effectively run and staffed by individuals who have economics or finance degrees. Thus, while economics is not an accredited field in the way of medicine or law,[4] it nevertheless trains and educates the individuals who go on to shape the dialogue around all major public policies. What is the educational background of individuals designing carbon emission schemes, international trade agreements, national interest rate policies, or global capital requirements for financial institutions? Yes, economics.

This should be a worry, but it is important to separate two different issues. The first is whether individuals working in the field of global trade agreements or financial regulation should have an understanding of their relevant political and historical issues. The answer to this question is of course yes. The second is whether or not the toolset provided by a standard economics training is necessary to understanding these issues. The answer to this question is almost certainly no. In other words, specialization of focus is different than specialization in training.

A standard economics training provides individuals with an understanding of statistics and mathematics. Economic models are very useful for thinking through the parameters and dynamics which govern a system redolent of some aspect of the economy, such a representative agent model.[5] These highly stylized models are the best anyone ca do in the face of complexity, but it is interesting to note that economics has opted to model economic phenomena closer to that of physics rather than biology.[6] There is not a convincing argument that only people who understand how to solve representative agent problems are knowledgeable enough to design trade agreements. This is because the vignettes that economics produces are just that – stories – not literal descriptions of our reality.

The Unbearable Lightness of Complexity

After a brief 6.4 billion kilometre trip taking about 10 years the Philae probe landed on the surface of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko about 510 million kilometers away from Earth. This is an incredible feat and marks yet another milestone in our species’ scientific and engineering accomplishments. However, while this seems like it a was a tricky thing to pull off, and no doubt it was, it was achievable because of the ability of understand a relatively simple system.[7] If the entire team of the European Space Agency was instead dedicated to forecasting the number of housing starts which would occur in Germany in six months from now, their accuracy would pale in comparison. This is because economic phenomena are inherently complex and are influenced by countless numbers of known and unknown factors which cannot be simultaneously modeled.

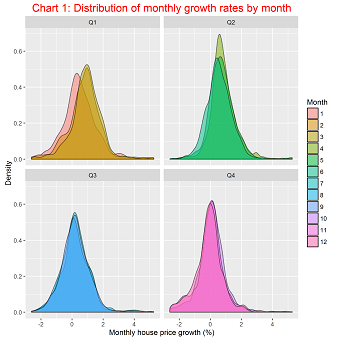

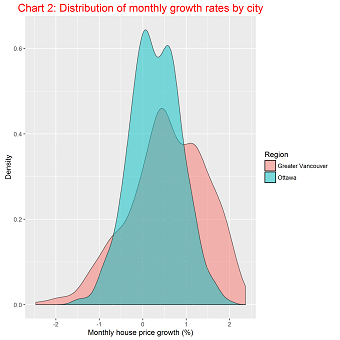

Let me provide one more example in the area of economics in which I work. Charts 1 and 2 found at the end of the post show the distribution of monthly growth rates in house prices across major Canadian cities, as well as Ottawa and Vancouver, over the last 10 years as specific examples using the MLS HPI. In the first chart we see that house prices see positive growth, on average, during only certain months. In the second chart we notice that the city of Vancouver has seen a much stronger distribution of growth rates than our nation’s capital. Can we ever hope to find a set of explanatory variables which could explain the distribution of house price growth by calendar months across time or space? No. The best we can do is provide a set of variables that may be able to explain some of the variation in outcomes we have seen over the last 10 years for major Canadian cities. Thus, we cannot ever hope to shoot out our economics space probe and land it on a theory that can even explain banal trends in the data. The shapes and trends found within the data we analyse gain social significance through the stories we tell about them, just as the distant stars gained significance through the fantastical images our ancestors ascribed to them before modern astrophysics was understood.

Friends, Roman, countrymen, lend me your ears

I come to bury the idea of economics as dentistry, not to praise it. Economics will never be dentistry. The former analyses a complex system whose trends can be understood in only a transitory sense, but whose deep and underlying structures as well as parameters remain a mystery. In contrast, dentistry operates within a closed biological system whose structures are fairly well understood and whose limits are set by the current engineering progress of medical science.

Economics should be understood as another method of story-telling. This is not to in anyway denigrate the field in which I have so far spent much of my higher education and career, but rather to acknowledge what it is. We should not seek to monopolize the discourse of public policy. In the end, I believe Keynes’ dental aspirations proved untenable because the ignorance and limits to correcting human teeth before WWII proved much more tractable to modern science than has the problems of economic systems. Furthermore, Keynes attributed the positive public perception of dentists due to their combination of being competent and humble. Somewhat perversely, the more competent and sophisticated economists have become, the more arrogant and less humble we find ourselves.

My vision of economics is a collaborative one: a discipline which works with psychologists and sociologists as well as computer scientists and biologists. When we once again consider the grandeur and delight of the Rosetta space probe landing at some distant speck of frozen ice millions of kilometers away from our planet, we must remember that this was a collaborative undertaking requiring many scientists with a wide range of backgrounds all working together. Where can such group collaboration be found within economics? What does our human genome project look like? Where is our Large Hadron Collider? The future, I fear, is one where we remain parochial and are seen as the pre-reformation clergy which sought to maintain their power through the monopoly of information and language. Instead of theological currency, economics risks appearing like it is hoarding the dialog and authority of public policy. The future I hope for is one where we allow a wider range of academic backgrounds to help us provide insight into economic problems whilst remaining humble to the limits of our knowledge.

Post script: A modest response

The above post received some helpful feedback from my friend Jamshid, and I have summarized his concerns and my response to each below.

- (1) Is economics just in an infancy stage of its science?

This is true in the sense that the mathematical modelling of human behavior is a relatively new science when compared to say physics (I believe Marshal’s principles was published around 1890), but it is a much older field when compared to say computer science, which has made much empirical gains in human knowledge (in my opinion).

What I would consider a “pass” for an infancy science is something along the lines of: look, we have these ideas, and our instruments are just too weak to be able to measure and validate them so we will have to rely on conjecture until such time that is possible to carry out these experiments. This is relevant for many of Einstein’s theories say, which were only confirmed by observational evidence decades later. However, in economics we do not have a set of experiments in which we agree if they were exactly carried out we would reach a consensus. The Oregon Medicaid study comes to mind where even though we knew exactly what the regressions we would run before we even received the data were going to be, we still didn’t agree on the conclusions.

- (2) Aren’t there areas of collaboration in econ?

This is also true when it comes to psychology in behavioral economics and say business schools in finance. But this is both rare (as in what percent of top economic journals articles have coauthors from non-economics departments? Less than 5% almost certainly) and we demand that other departments use the methodology of economists. In this sense its more along the lines of the economic imperialism as discussed by Lazear. This may also be true for fields like sociology, but it is not true for fields in say Biostatistics where biologists, statisticians, computer scientists, etc, each bring a skill set in a collaborative endeavor.

- (3) Does big data change any of this?

The answer could be potentially yes, but only if we agree of a set of experiments in advance that would determine the validity of a theory. In other words, if we don’t agree on what the channels of causation are in economic systems, then (to paraphrase Taleb), the bigger the data the bigger the mistakes.

Footnotes

-

Pronounced “kayhns”. ↩

-

Furthermore, these same textbooks make it clear that normative economics is what is discussed during Democratic Primaries and positive economics is what lines the pages of the august Journal of the American Economic Association. As a side note, in economics, the elite American universities dominate the intellectual discourse of the field through both their prestige and gravitational pull on all aspiring academicians. The Journal of the American Economic Association is to economics what Nature is to the sciences. ↩

-

I say ‘public’ deliberately because many would argue that the field began to move on from its classical origins of Adam Smith and David Ricardo by the publication of Principals of Economics by Alfred Marshall in 1890s. ↩

-

I don’t want this sentiment to be misinterpreted as I would not want economists to have to go through the equivalent of a bar exam, as professional accreditations are in part a form of rent seeking. However, a voluntary association for professional standards seems like a good compromise. ↩

-

For example, how the relative importance of fixed costs for businesses changes the competitive pressures in a market. ↩

-

By this I meant that stable constants and parameters are preferred over evolutionary processes. ↩

-

Again, I don’t want this sentiment to misinterpreted either! This project was of course staggeringly complex when compared to the everyday professional activities normal persons carry out. All I mean is that the physical rules that govern space travel are more comprehensive and tractable that say the folding of a protein or understanding the immune system. ↩