Other Minds by Peter Godfrey-Smith (Book Review)

There is something irresistible about the octopus. In the popular imagination the octopus is associated with its tentacles, an appendage which is menacing due to its ability to contort into strange shapes, extend to unexpected lengths, and suction unsuspecting prey. To suggest anything is tentacle-like does not imply a compliment. It is unsurprising that the cephalopod family, made up of Coleodia (octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish) and Nautiloidea (nautilus), receives a negative portrayal in popular culture. Examples include the sailor-menacing Kraken, the visual association with global conspiracies (octopus tentacles over the world), and, of course, their sexual association, made famous by Hokusai’s graphic painting.

It is with great relief that Peter Godfrey-Smith’s new book, Other Minds, provides a fresh and necessary portrait of a species whose natural life is largely unknown by the public and even the scientific community. To reiterate, most of our “knowledge” about octopuses[1] comes from glimpses of strange shapes in aquariums and horror films. This book is hard to categorize though. While its subtitle makes references to the Deep Origins of Consciousness, and the book does indeed discuss consciousness, it is more of a broad philosophical and evolutionary overview of the animal. I would cast this book as a vignette – a tour across the pertinent topics needed to understand cephalopods.

Figure 1: Cephalopods get a bad rap

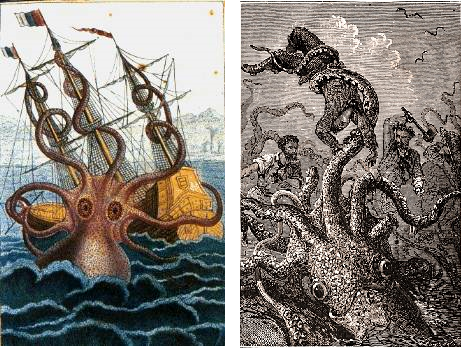

The book does do a good job at giving the necessary background for understanding the natural history of the cephalopods. If we went back 600 million years ago on our evolutionary tree, we could trace one the forking branches to a worm-like creature. It was at this juncture on the tree of life where we last shared a common ancestor with the modern cephalopods. The simplicity of this worm-like organism is important to note: all of the complicated biological systems our two species developed past worm-like level evolved independently. In contrast, if we look at our common ancestor we share with mice or monkeys, we would see that this organism already had eyes, rudiments of a nervous system, etc. Importantly, and hence the subtitle, the consciousness that both our species has developed has happened since we were (like) worms. Given the mysterious properties of consciousness,[2] it is surprising that it evolved in both species.[3]

Evolutionary biologists have discovered many systems that have evolved independently in several species such as eyes. However, eyes have a clear evolutionary advantage in terms of hunting, avoiding predators, and mating. If consciousness is merely epiphenomenal, then it seems surprising that it would develop in both species. Of course, it is possible that octopuses are not conscious, and they display complicated behavior in the same way that AlphaGo Zero does. However given that the octopus has a brain (more on that later) and is a DNA-based carbon lifeform, I am of the opinion that it is prudent to grant the creature an internal self-experience. The same admission could also be arrived at via the precautionary principle since failing to grant the animal a conscious experience when it has one would impose a cost far larger than mistakenly assuming it was conscious when it was actually just a philosophical zombie.

Figure 2: Where we departed with the Cephalopods

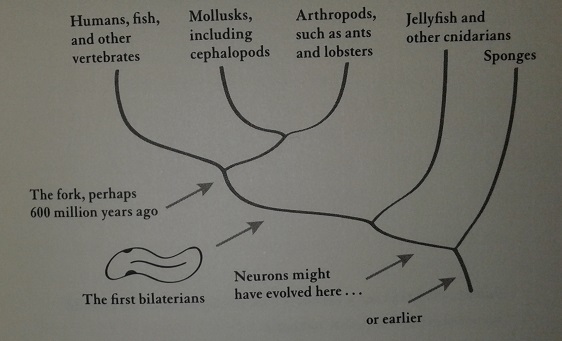

While the octopus is the best known of the cephalopods, there are actually four species in this class: (i) octopus, (ii) squid, (iii) cuttlefish, and (iv) nautilus (which is like a shrimp). Only octopuses and cuttlefish have been studied in any detail, so little can be said about squid and the nautilus does not appear to have sophisticated intellectual machinery. Figure 3 shows how the cephalopods evolved from their (cute) mollusk ancestors. Notice that except for the nautilus, the other cephalopods have all lost their protective armoring as they evolved. While the initial impetus for this adaptation could have been the trade-off between speed/defense or even developmental costs[4], this new armor-less species changed the evolutionary landscape.

Evolution works by iteratively selecting variants. Our species can, in principle, evolve into infinitely many new forms. But the same can also be said of say yeast. However, there are organisms that yeast could involve into that humans could not. Infinite does not mean everything (as paradoxical as the sounds). There are infinitely many prime numbers, but not all numbers are primes, for example. Because the initial state matters, evolution is highly path dependent. It is reasonable to believe that by shedding their armor, just as humans shed some of our strength and agility,[5] the evolutionary landscape of cephalopods changed so that they could evolve into more “intelligent” lifeforms. Without a protective casing, these animals had to outcompete other species and their internal rivals with more cunning.

Figure 3:

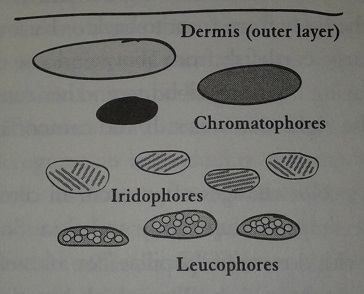

The most novel material for me in this book was the discussion about the cuttlefish. While the octopus and squid can also change the color of their skin, the cuttlefish is the master at this. These species all have chromatophores, a pigment-containing cell just below their skin, that can change color by being stretched by the muscles (see Figure 4). Because a cuttlefish will has around ten million chromatophores, it is the equivalent of having a ten megapixel screen on its body! The author, having spent some time observing the cuttlefish underwater, began to notice that certain cuttlefish display patterns in an almost artistic like way.

Some individuals, friendly or not, have distinctive styles of color change. I’ve occasionally encountered cuttlefish who seemed to produce colors the others had not quiet thought of, or patterns with particular brilliance. The first of these I named Matisse. He was a friendly cuttlefish I visited for several days some years ago. All his colors had particular detail, but something else set him apart. He would be hovering without fuss in some mixture of reds and whites, and would suddenly explode into bright yellow. This flood covered his entire body, with no other marks visible, and would be switched on in less than a second. One moment he would be dark red, with veins and stripes, and in less than a second he looked like a cuttlefish-shaped sun. The flare would then fade, more slowly. Oranges would appear among the yellow, and darken. Patterning would return. In ten seconds or so he was dark red again.

Cuttlefish have sufficient control over their chromatophores that they can have a pattern displaying on only one side of their body. I suspect that the artistic expression of color might be similar to way that animals enjoy stretching their muscles, or humans enjoy cracking their knuckles. There is certain pleasure that comes from exercising control over our body, and I should not think it any different with the cuttlefish.

Figure 4:

The book spends a lot of ink (pun?) on consciousness, although a good portion of it is not about octopus consciousness in particular. These sections reveal Godfrey-Smith to be the philosopher that he is! While the material was interesting, because I happen to be interested in this topic, other readers may not be taken by some of the superfluous detail. To be fair, it may be that the text has enough material to bring about a coherent argument about the unique properties of consciousness, and how studying the octopus sheds light on some universal properties of internal experience, but a reader will not be able to assemble a compelling narrative on their own.

However, one will come away with some interesting facts. Consciousness in a octopus may be localized in several compartments. While we are pretty sure that our limbic system is not conscious, the tentacles of an octopus just might be. Each tentacle contains its own nervous system and appears to be able to carry out autonomous exploration. At the same time, scientific experiments have shown that the brain of the octopus can ultimately control the direction of its tentacle, but it is a slow process. Imagine that your arms and fingers moved without any conscious control (just like you heart beating), but with great concentration you could exercise some power over them. However, even if you could get your arm to move in the right direction, your fingers may still wiggle around independently. This may be what it feels like to an octopus!

A mediocre book can sometimes be made a pleasant read when ones expectations were initially low enough. In contrast, Other Minds felt somewhat disappointing to read simply because I brought such high expectations towards it. The book has two fundamental problems: (i) there is an insufficient overarching theme or narrative (hence why I called it a vignette), and (ii) it is insufficiently developed. It is a short book, around 250 pages, and 50 of those are for endnotes, most of which are just references to journal articles.

Perhaps this is not Godfrey-Smith’s fault because most of the modern research on cephalopods has happened in the last ten years and we are only now just beginning to understand this remarkable species. However, even with our current state of knowledge this book could have done better. Where is the chapter on the cultural history of octopuses in literature (even Wikipedia has a page)? Where is a chapter that provides a textbook-like background on the cephalopods (detailing the tentacles, their mating cycles, the relative size of males to females, etc). One sensed that the publishers were happy with the limited material contained in the book and wanted to get it out for 2017. Despite these criticisms, the book is interesting and I would put it in the category of books that are worth taking out from the library when they became available.

Footnotes

-

No not Octopi. Apparently the Latinate suffix is no longer (was it ever?) the right declension. ↩

-

It’s a notoriously hard problem. ↩

-

I am defining, as is common, consciousness as anything that feels like something to be something. ↩

-

Natural selection can encourage adaptions which lower the survival odds of a species later in life if there is some advantage early on. In the case of the cephalopods, it could be that by shedding their energy-heavy shell, their ancestors ate and mated more in their early years. If these early gains outweighed longer life spans (since armor presumably keeps you alive longer), variants that reduced the size of the protective encasement would be selected for. ↩

-

A chimpanzee is much stronger than a human. ↩