Nigeria by Richard Bourne (Book Review)

Background

Seventeen African countries achieved independence in the year 1960. Among this list was Nigeria, the continent’s most populated country and the regional leader of West Africa. The disintegration of the British and French empires happened faster than almost anyone would have predicted five years before. Though each country’s post-independence experience was unique, many of the economic and political challenges were the same. Borders based on a European scramble for colonial possessions meant that nation states often had an unwieldy collection of competing ethnic groups each with access to different natural resources. Because the colonial authorities were concerned that mass education would make indirect rule politically impossible, there were only a handful of educated elites at the time of independence who were capable of running a modern nation state. No country embodied the twin problems of problematic borders and diffuse ethnic coalitions more so than Nigeria. A highly readable account of the crippled giant’s fascinating and turbulent history since independence can be found in Richard Bourne’s Nigeria: A New History of a Troubled Century. The book is written for a popular audience and little background knowledge is needed for a novice reader to enjoy it. However an understanding of some West African history, as well as knowledge of Nigeria’s key historical figures, will enhance the reading experience.

Anyone who claims to understand Nigeria is either deluded, or a liar. It comprises so many ethnicities and perspectives, with a contested past and statistics to be taken with pinches of salt, that it is an act of immodesty to write a centenary history.

Nigeria’s demographic tensions can be understood along three overlapping dimensions. A Muslim and Christian divide can be seen between the north and south. Internal migration during the colonial era meant that congregants of both religions are to found throughout the country. For example, the Sabon Gari’s of the North were the ghettos where Southerners tended to reside. At independence the North of the country was seen as sociologically backward compared to the Christian South. As part of Lugard’s policy of indirect rule,[1] Northern emirs were given free reign over local administration, with fealty only to overarching British foreign policy. Many of the Nigerian troops that fought with the British in WWII (see the 81st and 82nd divisions) were drawn from Northern regions, and the emirs even donated to the war cause. The British in turn helped the emirs keep out Christian missionaries and southern agitators. As a result there were almost no formal schools in Northern Nigeria at the time of the independence (beyond the Islamic madrassas), and the vast majority of the population was illiterate.[2]

A strange phenomena that often happened in the British empire was the romanticization of a specific ethnic group in the country (often the one that most reminded the officer class of the Scots). For example the “Pathans” (e.g. Pashtuns) were seen as the noble light-skinned and green-eyed warriors in contrast to the sycophantic “Hindoos” of the Indian subcontinent.[3] Lugard, though responsible for military capture of Northern Nigeria with a force of only 2000 troops and 200 British officers,[4] became sympathetic to the Islamic states with their clear feudal hierarchies and Durbar pageantry.

The vast majority of the inhabitants were not only completely unaware that they had been allocated to Britain but were ignorant of the very existence of such a country. Nor were the bulk of these peoples primitive and unorganised tribesmen whose subjection, when Britain was ready to claim it, could be taken for granted: the region contained some of the most highly developed and civilised Muslim states of tropical Africa, centred upon walled cities and defended by armies of horsemen.

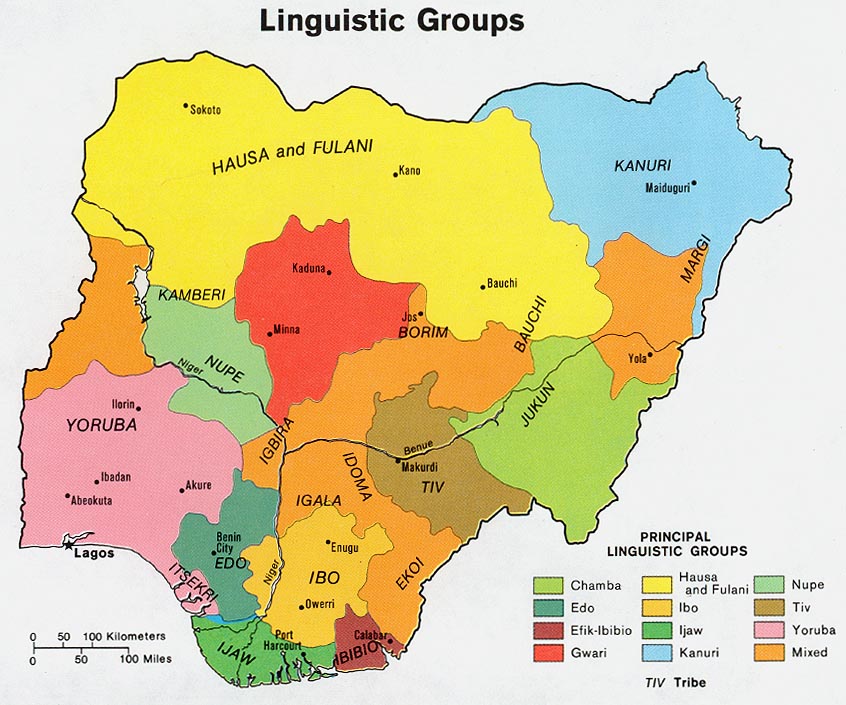

A Durbar in Northern Nigeria circa 1960

Nigeria’s second demographic split was amongst the three largest ethnic groups: the Hausa-Fulani in the North, the Yoruba in the South West and the Igbo in the South East. Despite the Igbo and Yoruba both being Christians,[5] there has rarely been a stable “Christian” political coalition in Nigeria’s history. Yet this ethnic trichotomy glosses over the numerous ethnic minorities that make up the rest of the country (about 33%). For example the well-known environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa was an Ogoni and the former president Goodluck Jonathan was an Ijaw. Bourne does a good job at avoiding simplistic narratives about “ancient hatreds” throughout his book when explaining the country’s shifting political tides.

Nigeria's ethnic trichotomy hardly captures the country's complexity

As Nigeria careened towards independence in 1960 there was oscillating pressure to either centralize or federalize the country. Though a centralizing state would help to reduce regional imbalances, it would inevitably become the site of struggle for each group wanting their turn to eat. One wonders whether a purely federated Nigerian state would have prevented the country’s civil war from occurring, or whether the corruption and environmental damage caused by the oil industry could have been reduced. Some of the country’s challenges would have been inevitable though. Under Britain’s colonial rule, large numbers of minorities moved into adjacent territories for economic opportunities.[6] For example a clash over the imposition of Sharia law on Northern Christians by the Alkalis was a foreseeable risk. And could a central state have allowed the discovery of massive hydrocarbon reserves in the South East to enable a state government to exceed the fiscal capacity of the federal government?

Independence

Nigeria’s independence occurred at the height of the cold war. Lumumba had been overthrown by a coup a month before in the Congo, and the Cuban revolution was still fresh in the minds of the Americans. Luckily, from the Western perspective, the country’s first prime minister Abubakar Tafawa Belawa was a pious Muslim, conservative, and not at all interested in the Soviet bloc.

How was it that Balewa became the first elected prime minister of a sovereign Nigeria, in what in retrospect was called the First Republic? Had the British, possibly for Cold War reasons, fixed the 1959 elections so that this cautious and Anglophile northerner, with several wives as a good Muslim and 22 children, became the leader at independence?

Probably not. Even though the two Southern Parties, the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) and the Action Group (AG),[7] had enough seats to form a majority coalition, the Northern People’s Congress (NPC) aligned with the NCNC to form a government. Awolowo and the Yoruba-dominated AG overplayed their hand by trying to make deals with the NPC and NCNC simultaneously. Yet once the NPC and NCNC realized their suitor “cheating” on them, AG was left in its role as the official opposition. When Nigeria became a Republic in 1963, the British government still had a large degree of influence in the fledgling country. Though Nigeria was already showing a tendency towards ethno-regional political coalitions, the Macmillan government was happy enough that it remained a friendly member of the commonwealth. The Labour government was desperate to distance itself from the embarrassment of Nkrumahism in Ghana, white flight in the Belgian Congo, and the South African apartheid government’s Sharpeville massacre.

Nigeria was at a crossroad after independence. Nnamdi Azikiwe in his inaugural address as Governor General appealed to Awolowo and the Sardauna to forge a new country that was “hate-free, fear-free, and greed-free” and act as a shining example to the continent.[8] Yet the dream would fail. In seven years Nigeria would experience two coups and one of the bloodiest civil wars in modern African history.

The trouble for Balewa and those trying to make a success of an independent Nigeria was that public expectations were excessive, the economy would have difficulty paying for them, and politics seemed the easiest way to make money. ‘Nigeria’ was becoming a deadly combination of a zero-sum game and roulette. The honeymoon joy of independence was the prologue to a deepening crisis.

After becoming a republic in 1963 by severing all official links to the British monarchy, Nigeria began to chart its own foreign policy course. Though by no means aligned to the Soviet bloc, Nigeria’s foreign policy soon became at odds with its former colonial ruler and the NATO bloc in certain regards. The country applied constant pressure to Britain to sanction Rhodesia and was one of the loudest voices condemning apartheid. It also protested against France’s nuclear tests in the Sahara and even temporarily ended diplomatic relations with her in 1963. This slight against France may have been the reason for French support of the Biafran rebels four years later. Nigeria also cancelled its defence treaty with the UK.

Overture to disaster

The political arrangements at the time of independence quickly began to fray within a few years. The NPC was much more successful than the NCNC in getting northerners into military and civil service positions. Cut off from the centre, the NCNC focused instead on shoring up its control of political offices available in Igboland. The opposition AG party split into two halves, with Samuel Akintola leading a more “moderate” group that wanted to negotiate with the NPC, in contrast to Awolowo, who continued to oppose any deals with the federal parliament and advocated for the nationalization of key industries.

In 1965 the Nigerian train of state went off the tracks. Rigged elections in the Western region led to a series of riots and communal violence. The government seemed incapable of formulating a response. As frustrations mounted within the country, a group of young army officers launched a coup which killed the prime minister, the Sardauna of Sokoto, and senior military leaders just a few days after after Balewa returned from a Commonwealth conference in Lagos.[9] The chain of events over the period 1965-1970 would be Nigeria’s most fateful and its most contested. Were the coup plotters driven by idealism or ethnic factionalism? Could a clash of interests have been prevented by shows of leadership from Nigeria’s founding fathers? Was the democratic infrastructure of the country bound to collapse under its own contradictions?

The full order events was as follows. First, a group of young army officers (mainly Igbos), led by Nzeogwu succeeded in killing the prime minister and premiers of the Northern and Western regional governments (Bello and Akintola). The plotters failed to neutralize the head of the armed forces, Aguiyi-Ironsi, who though an Igbo, was seen as loyal to the existing government. Second, Aguiyi-Ironsi was able to re-establish control over the Nigerian army and most of the coup plotters were either captured or went into exile. However many Northerners were wary of the new government and believed that Northern officers would be sidelined under his administration and another coup was launched which succeeded in capturing and later killing Aguiyi-Ironsi.

Many of the participants of the 1966 counter-coup would play a prominent role in Nigerian political life for many decades to come. These included Murtala Mohammed, Danjuma, Babangida, and Abacha. Amazingly, Muhammadu Buhari who took part in the coup at the age of 24, would first become the military head of state two decades later, and then be elected as president three decades later in 2015! The political lifespan of the Nigerian politician is a long one. The fall of the First Republic in Nigeria has many parallels to the crisis of the Roman Republic. In both settings a handful of powerful men were vying for control over immense populations and spoils. Legitimate political motivations mixed easily with raw power politics. The elites were well educated (most of Nigeria’s military and political leadership studied in Britain), knew each other well, and were raised in an intense atmosphere of competition.

The generals

Nigeria’s third quarter-century was disastrous… It included two breakdowns of civilian democracy; a war between Nigerians with anything up to three million casualties; institutionalised corruption at the level of the state, which was linked to extraordinary national dependence on oil revenue, alongside continuing poverty; and the arrival of the military in politics that, purporting to be an instrument of national unity, came to be seen in the south as an armed agent of northern hegemony.

After the coup of 1966 Yakubu Gowon was chosen to be the military head of state and would rule the country during its devastating civil war and subsequent enrichment during the oil boom. Gowon, though from the North, came from a minority group and was likely chosen to offset the appearance of the coup being a pure Hausa-Fulani affair. However the counter-coup unleashed a torrent of communal violence and many Igbo were killed throughout the country. Further moves by the federal government to break up the Eastern region led to a formal declaration of independence by the Nigerian army officer Ojukwu and the short-lived Republic of Biafra was born in 1967.

Once again Nigeria’s history seems to be characterized by an irresistible force moving towards disaster. The country’s civil war (also known as the Biafran War), was a humanitarian catastrophe with millions of civilians killed or displaced. In contrast, military casualties were relatively light (hundreds of thousands). Gowon actively pursued a policy of blockades and starvation to force the Biafrans into submission. Which, one could argue, succeeded at immense cost. Colonel Obasanjo, who would later become the military head of state, accepted the surrender of the Biafran forces in January 1970. An amnesty was given to almost all of the Biafran leadership. Gowon’s magnanimity in victory set a precedent: despite the obvious fissiparous tendencies the elites of the country were committed to keeping it whole. Whether this motivation came from a sense of national pride or the desire to have the largest extractable rents possible, no one can be sure. Since Biafra, and possibly because of its brutality, Nigeria has gone through numerous coups but has avoided any serious risk of a civil war.

The federal victory in the civil war did not put an end to the existential question about the Nigerian state – whether so many different peoples can live together amicably in one polity. But it recast it. It demonstrated that there are military, political, and economic forces strong enough to counteract and defeat the centrifugal and fissiparous tendencies. It showed that where was not some southern unity of Igbos, Yorubas and the ethnicities in the Delta, that could overthrow a perceived hegemony of the north. It showed that the north itself was not a single uniform bulldozer, but a mosaic of groups with different interests and different appreciations of Islam. And above all it showed that the minority tribes all over the country were committed to the survival of a reorganised federation, in which their voices could be heard and the Nigerian army would not allow the Nigerian experiment to fail… [T]he federation that emerged at the end of the civil war was not the one that had won independence from Britain. The decree that created twelve states opened the door to a greater sense of ownership of Nigeria beyond the hitherto dominated Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, and Igbo; it also opened the door to continuing pressure for more states, recognising ever smaller ethnicities, which was still not entirely assuaged when the Abacha regime moved to a total of 36 in the 1990s.

Though Nigeria’s economy was poorly managed throughout the 1970s by Gowon, Murtala Mohammed, and Obasanjo, the oil price shock led to a spectacular rise in government revenues. The state has remained hooked on petrodollars ever since. Even today, oil accounts for more than 90% of Nigeria’s export earnings and 65% of government revenues. The conundrum facing the political leadership was, as General Gowon was once remarked, not money, but how to spend it. As a consequence the size of rents extractable from the state led to corruption on a different scale: [T]he private jet became a status symbol in Nigeria whereas most African elites had to make do with the Mercedes Benz. Without needing to tax its citizens, Nigeria’s military rulers saw no need to diversify the economy or invest in human capital. Obasanjo’s disastrous policies of indigenization and nationalization removed the last semblance of corporate governance from the country.

State control, underpinned by the rapacity of the executive, had been disastrous not only in the telephone monopoly, but also spectacularly in the robbed and underfunded electricity supply company, Nigerian Electricity Power Agency. NEPA – ‘Never Expect Power Always’, as it was nicknamed – had built no new power stations for a decade and could only provide 30% of households with an intermittent supply, and the majority of businesses, like better-off families, relied on diesel generators.

It is has often been noted that military governments are poor economic stewards because the command-and-control attitude of the battlefield is hardly suited to the subtleties of a market-based economy that fundamentally rely on incentives and forces beyond state control. During the Buhari regime (1983-5), state policies approached the farcical, including the Orwellian sounding War Against Indiscipline. NCOs were mobilized around the country to ensure “discipline”, which included making sure Nigerians were forming proper queues. One of the more colourful moments during the Buhari regimed was the Dikko affair, in which a former minister who had stolen billions of dollars from the treasury was kidnapped in a joint Nigerian-Israeli operation and almost smuggled out of the United Kingdom in diplomatic bag.

During the period of military rule Nigeria became a byword for corruption. Of course rent seeking in the early Nigerian state can be traced back to at least the 1950s. Already the Western Regional Tenders Board, the Northern Contractors Union, and the Eastern Nigeria Civil Engineers were awarding contracts to firms with connections to their respective political parties (i.e. the AG, NPC, and NCNC). Corruption reached its peak during the Abacha era. After his sudden death (reportedly in the company of Indian prostitutes), his wife Maryam was caught with 38 suitcases of cash on her way to a catch a flight leaving Abuja. Nigeria to this day continues to recover funds that were squirrelled away during the Abacha era.

Okotie-Eboh became notorious, like Kingsley Ozuomba Mbadiwe, Minister of Transport, as one of the ‘ten per centers’, the ministers who were collecting commissions on projects they approved… He triumphantly survived a storm in the House of Representatives after he had started a shoe factory and then increased the duty on imported shoes.

Concluding thoughts

The fathers of Nigeria’s national consciousness like Macaulay, Azikiwe, and Awolowo began their education at a time of optimistic nationalism. Each channelled their frustration and excitement into respective media outlets: the Lagos Daily News, West African Pilot, and the Nigerian Tribune. Sadly both Azikiwe and Awolowo would die when their country was ruled by military dictators (Abacha and Babangida, respectively). Yet with election of Buhari in 2015 and his re-election in 2019, Nigeria appears to have a firm dedication to democratic rule. The former general’s commitment is hopefully representative of current army leadership. The Nigerian military’s incompetent handling of the Boko Haram insurgency has likely undermined its legitimacy as an alternative option to civilian rule. However the return to democracy has not removed the unholy nexus between business and politics.

Nuhu Ribadu, when chairman of the anti-corruption body, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), said in 2007 that 23 of 36 state governors were wanted on corruption charges and that he was taking steps to prevent them leaving the country… Peter Odili, People’s Democratic Party Governor of Rivers state, was singled out by Ribadu and the EFCC in 2007 for extensive fraud and corruption and was spending less on education in the state than on his own security.

Though centenary histories can often be dry, Bourne’s Nigeria is written in a easy and light-hearted manner. It is clear that Bourne is deeply interested in the country and sympathetic to her history. He is also funny throughout: the United Peoples’ Party then morphed into the Nigerian National Democratic Party, not becoming notably more democratic along the way. The author was able to interview several important people in the book including Maitama Sule, the first and last resource minister who was (apparently) not corrupt and who helped break up the Shell-BP and ‘seven sisters’ cartel on oil bidding. Sule also told the author that Belawa avoided the temptations of his office. From all accounts Tafawa seemed like a Muslim gentleman worthy of his Knighthood. Although it’s important to note that “Balewa completely failed to call any of his ministers to account or punish them for their misdemeanours”.

The dissatisfaction with the Nigerian body politic was widespread, and it was displayed in the press, in the labour movement, in the dubious federal election at the end of 1964 and in its aftermath. At independence, only four years before, it would have been inconceivable that, so few years later, Chief Awolowo would have been incarcerated for treason in the 19th-century prison in Lagos. What few realized was that the anger with the slow pace of decolonisation and the corruption of the politicians was beginning to take hold in the military.

The Nigerian government is an example of what Lane Pritchett calls a flailing state: a principal that cannot control its agents. Alex Tabarrok would likely argue that Nigeria should be governed under the principle of presumptive laissez-faire. Though there are clearly many government interventions that would improve Nigeria’s economic fortunes, the problem is there are almost no Nigerian state actors that could carry out such policies. For a country with limited state capacity, it should demonstrate competence in key areas before moving onto more complicated interventions like tiered exchange rates or rice self-sufficiency.

As a natural critic and someone drawn to the excitement that occurs when something goes off the rails, one needs to be careful not to solely focus on Nigeria’s catastrophes and also acknowledge its accomplishments. The country has a long tradition of peacekeeping in the UN and the AU going back to the Congo. Nigeria arguably has Africa’s most vibrant press sector which dates to its pre-colonial era. The country is now the largest economy on the continent (surpassing South Africa in 2016) and is on track to have the third-largest population in the world by 2050. Nigerian culture highly regards educational attainment and learning. This explains why Nigerian-Americans have the highest share of graduate degrees for any demographic group in the United States. Although I am based, Nigeria’s most impressive accomplishment may be its its literary culture which produced the likes of Adichie, Achebe, Okri, Oyeyemi, Tutuola, Okigbo, and Soyinka. One of my takeaways from Bourne’s book is that sometimes the people don’t get the government they deserve.

The trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership. There is nothing basically wrong with the Nigerian character. There is nothing wrong with the Nigerian land or climate or water or air or anything else. The Nigerian problem is the unwillingness or inability of its leaders to rise to the responsibility, to the challenge of personal example which are the hallmarks of true leadership.

The Trouble with Nigeria (Chinua Achebe)

Footnotes

-

Lugard was the first governor-general of the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria and the intellectual architect of indirect rule. He also formulated the concept of the “dual mandate” which combined a mission civilisatrice with economic exploitation for the mother country. Though indirect rule may have been well-suited to allow British traders and investors the ability to profit from resource extraction by co-opting existing tribal systems of government, it clearly was in tension with the “civilizing” project of abolishing slavery, for example. ↩

-

A notable exception to this was Katsina College which educated many of the Northern elite including Balewa, Bello, along with other presidents and military rulers. ↩

-

Kipling’s Indian Tales are a good place to see this strange aspect of British racism on display. ↩

-

The Maxim gun and British discipline enabled the capture of the North’s major cities (Kano, Sokoto, Katsina, Zaria) and the concomitant capitulations of the Fulani emirs. ↩

-

It should be noted that the Igbo are disproportionately Catholic relative to the rest of the country. ↩

-

The British invested a significant amount of resources into the development of the country’s railways which allowed unprecedented internal mobility. From 1964 to 2003 the annual number of passengers declined from 11 to 1.6 million and freight traffic almost collapsed. The Lagos-Kano route which began in 1912 and has since disappeared may once again be resurrected by a Chinese state rail company. ↩

-

The reader of Bourne’s Nigeria cannot help but notice many of the fascinating characters that make an appearance. Herbert Macauley, one of the co-founders of the NCNC (along with Azikiwe), is one such a figure. Considered the father of the Nigerian independence movement, he was educated at a grammar school in Lagos in the late 19th century and went on to become the proprietor of the Lagos Daily News which was a constant thorn in the side of Lugard and the colonial authorities. Nigeria’s claim to have the continents most rancorous and open media can be traced all the way back to Macaulay. He once memorably stated: “The dimensions of ‘the true interests of the natives at heart’ are algebraically equal to the length, breadth, and depth of the white man’s pocket”. ↩

-

Zik, as he was usually referred to as, is a good example of Nigeria’s complicated ethno-regional divide. Though formerly associated with the NCNC (with he co-founded with Herbert Macaulay) and Igbo nationalism (being a spokesman for the short-lived Biafran Republic), he was born in Northern Nigeria, spoke fluent Hausa before learning Igbo, and then ultimately went to Lagos where he learned Yoruba. ↩

-

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche’s Half of a Yellow Sun, most of Olanna’s Igbo family are delighted to find out that Sardauna was killed as they associate him with Northern oppression and corruption. ↩