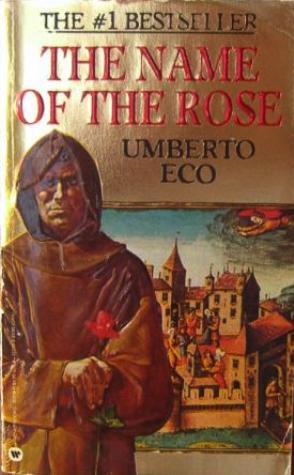

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco (Book Review)

I went into reading The Name of the Rose with high expectations both because I had enjoyed one of Eco’s other works (Baudalino) and because the novel is considered one of the author’s best. It did not disappoint. Eco’s writing style is similar to two of my other favourite authors: Italo Calvino and Jorge Luis Borges. These authors are all thoroughly postmodern and draw heavily on intertextuality (references to other works of literature). The Name of the Rose is set in 14th century in Italy at the peak of the High Middle Ages. The historic background is one of total corruption in European society with every strata of the religious hierarchy focused on personal gain rather than religious devotion. The period marked a peak in the tension between the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire, with ongoing disagreements about the separation between secular and religious affairs being adjudicated by force, if necessary. Due to a complicated set of political circumstances, the papacy was actually located in Avignon in Southern France throughout most of the 1300s.

The novel unfolds from the perspective of a Benedictine novice named Adso of Melk. He is travelling under the tutelage of the senior Franciscan friar William of Baskerville who has been requested by the emperor to help adjudicate a dispute between Pope John XXII and various Franciscan sects over the issue of Apostolic poverty. The parley is scheduled to take place in a week from William’s arrival at an abbey designated to be neutral ground in Italy. The reader soon becomes aware that William and Adso are a Holmes and Watson duo (if the Baskerville toponymic surname wasn’t enough of a clue). In the first scene with William, he deftly infers the that abbot’s horse has gone missing by observing tracks in the snow and broken branches. When Adso presses to find out the source of William’s knowledge, he is told, in so many words, that it is a rather elementary deduction! When they arrive at the abbey, the abbot asks William to conduct an investigation into a monk who is assumed to have been murdered.

As each day unfolds another monk is found dead and the urgency for the William and Adso duo to solve the murder increases. The book is broken into seven parts (one for each day), and each day is broken into chapters corresponding to the canonical hours. As the mystery begins to unravel it becomes clear that the source of the conspiracy is related to the abbey’s mysterious library, which is described as the greatest in all of Christendom. The library is structured as labyrinth (a reference to Borges quite possibly) so that only the master librarian is able to locate the books. William debates many of the monks as to the ethics of keeping a library’s information hidden from scholars. The abbey’s view is that knowledge must be regulated to prevent heresies and falsehoods from from polluting Christian thought. Being a disciple of Roger Bacon, William’s view of natural philosophy is that only those true ideas in accordance with god’s majesty will stand the test of debate and inquiry.

The novel has three sorts of scenes. The first are those of any detective procedural where William and Adso are gathering evidence and speculating about motives. The second are long discussions or debates between William and other characters on intellectual subjects including theology, science, politics, and history. Because William appears to have read every book in the middle ages from Latin, Greek, and Arabic sources, he is full of fascinating insights. The third type of scene focuses on the internal state of Adso as he suffers humiliations, strange dreams, and epiphanies about the case. Each help to nicely balance each other out with Adso’s naivety being endearing and providing well-needed comic relief.

While it is hard to describe The Name of the Rose as an easy read, it was nevertheless difficult to put down. My paperback ran over 600 pages but I finished it within the same time I usually read 300 page books. It is surprising that a book with hundreds of untranslated Latin expressions and references to long-dead popes and obscure heretical groups became a commercial success. While many parts of the book escaped my comprehension (and no doubt others too), by recreating such a intricate medieval world, Eco allows the reader to feel at home even though the sensory stimulus is at times bewildering. This book was one of the best I have read this year, and it receives my hearty endorsement.