Men of Honour by Adam Nicholson (Book Review)

A seaman should be understood to be quite different from all other classes of men, he does not spring up like a Mushroom, it requires many years to make him a seaman, with fatigue both of body and mind. (Henry Bayntum)

The British self-image is that of an “Island Race” ensconced in a “fortress built by Nature for herself”, ready to “defend our island, whatever the cost may be”. Throughout most of Britain’s history the Royal Navy has ensured that no foreign power would be able to deploy troops on her mainland. Britain’s command of the seas was from the Age of Sail to the Second World War by destroying hostile navies including the Spanish, Dutch, French, and Germans. The most famous naval victory of the Royal Navy is of course the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. A British fleet of 33 ships would attack and route a larger Franco-Spanish fleet of 41 ships, destroying or capturing 22 of them without a single loss on her own side. The savagery of the British attack can be seen in the 15,000 casualties sustained by the French and Spanish compared to the 1,500 for the Royal Navy.

Not once or twice in our rough island-story,

The path of duty was the way to glory

Tennyson

The battle gave the British two lasting cultural legacies. First, it cemented the idea that Britannia does indeed rule the waves. Second, it offered the heroic death of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson as a benchmark for how an honourable English commander was to die in combat. Published on the 200th anniversary of Trafalgar, Adam Nicholson’s Men of Honour attempts to explain the British victory at Trafalgar through cultural and psychological forces. The book acknowledges that it cannot compete with the rigour found in military histories written by professional historians or academics. Instead the book brings together material from literature, poetry, politics, and the history of the Royal Navy to better understand this seminal event in warfare.

The three core demands of a navy – to supply and fit itself; to survive the sea; and to kill the enemy – were understood in Britain to be part of a single integrated whole. In both Spain and France, that single organism was institutionally divided into conflicting and competing parts.

Nelson’s personality is the dream of every biographer. He could be moody and dour but also affectionate and humorous. He was the son of Norfolk parson who was also related to various royalty. He benefited from his family connections but also worked hard to work his way up the chain of command and commanded ships during the wars of the American and French revolution and, of course, the Napoleonic wars. By 1805 he would have struck a noteworthy pose with a missing arm and one working eye. Given the amount of exploding shots, shells, and shrapnel in the era, all naval men eventually lost some limbs. Before the death of Nelson there were two paragons of military heroism: Achilles and Aeneas. Achilles channelled a Greek individualism – a noble warrior who fought for his own honour and interests. Aeneas embodied the Roman virtues of the brave soldier who fought for a larger state or polity. Nelson somehow managed to channel both heroic paradigms by being both a stalwart officer of Albion (“England expects that every man will do his duty!”) and ruthlessly climbing the naval hierarchy and claiming prize money whenever possible.

That twin inheritance, the Virgilian and the Homeric, are both in play at Trafalgar and both are fused with the contemporary passion for a burning apocalyptic fire.

Nicholson’s style of writing about “nations” and “peoples” in history seems anachronistic in the era when historians are expected to be increasingly quantitative and objective. Men of Honour asks such Churchillian questions as: why was the British psychology so aggressive whilst the French and Spanish so placid and defeatist? Why did Villeneuve want to avoid an engagement when his navies had more men and cannon? Nicholson believes that the British were instilled with a sense of aggression because they believed in the righteousness of their cause. In 1805 there was nothing wrong with wanting glory, even if in reckless pursuit, in order to secure the necessary income, titles, and rewards that were the spoils of Napoleonic warfare. Not only are the British seen as superior in some sense, their Gallic counterparts are seen to suffering from both a surfeit and dearth of republicanism. The Spanish elites, while brave, are presented as decadent and backwards. The French admiralty are described as the traumatized remnants of the country’s gentry: “Navies reflect the societies from which they come”.

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson

Something must be left to chance, nothing is sure in a Sea Fight beyond all others. Shot will carry away the mast and yards of friends as well as foes … Captains are to look to their particular Line as their rallying point. But, in case Signals can neither be seen or perfectly understood, no Captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an Enemy.

Nelson’s memorandum to his captains two weeks before battle.

On a technical level the problem with arguments about “national character” is that it is never clear how much variation in aggression, pluck, and inventiveness occurs between as opposed to those within nations. My sense is that for conflicts between countries with similar levels of technological sophistication and economic development, most of the variation in military outcomes is due to strategic considerations or random chance. I believe cultural arguments can be made when describing the reasons for Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union or British reluctance to invade mainland Europe in the second world war.[1] However I don’t think cultural forces help to explain “passivity” or “aggression” on the tactical level. Military doctrine perhaps, but this is related to institutions and incentives which are quite different. The passage below is emblematic of the a Nicholsonian view of history.

By the time of Trafalgar, England had not only been long subject to an expensive and threatening war. She was deep into the social transformations which a commercial revolution had worked, and had, as a result, become a more serious place: tense, anxious, interested in material facts. War and commerce had rubbed away the frivolities which a previous age had come to see as normal and natural. A new roughness and harshness was in the air… William Pitt died at the age of forty-seven, a victim of incessant work and compensatory drinking. One minister after another committed suicide, most by cutting their throats. Nineteen members of parliament killed themselves between 1790 and 1820. More than twenty went mad. Both Russian and real roulette became the diversion of the moment. Duelling and gambling enjoyed a resurgence they had not known since the 17th century.

At many points in Men of Honour it becomes clear though that a nationally romantic view of military psychology seems unaligned with many of the facts. In the Royal Navy for example, “half the people … were either pressed men or miscreants sent on board as part of a quota from each country, and a sixth of the entire fleet would desert or attempt to desert in the coming year (an average kept up throughout the Napoleonic war).” Another criticism I have of the book is that the author employs naval and ship terminology that I found incomprehensible. Without access to Google I would have been baffled numerous times. A diagram which delineated the difference between the bowsprit and the poop deck would have been useful. To someone who is not a naval history buff certain sections will seem too prolix.

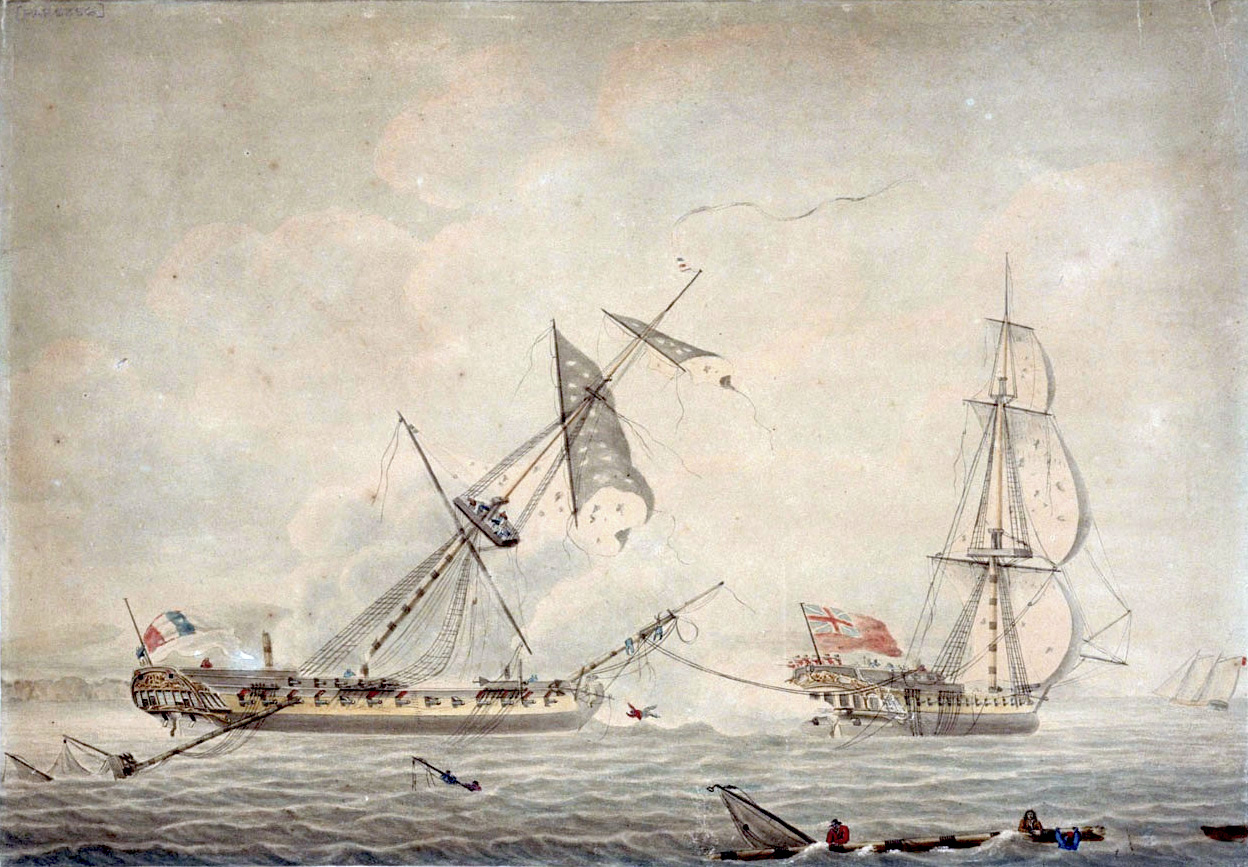

In the late 18th century enemy ships were captured for significant monetary prizes

Despite some of its weaknesses I still enjoyed reading Men of Honour and found myself learning quite a lot. One of the things I found most interesting was the importance of prize money that (mainly) captains received in payments for captured ships. Piecemeal pay was common for government positions in the era before a permanent civil service. Men like Henry Digby are an excellent example of someone who got fabulously rich through their military career. Prize money may have been a motivating factor for many captains in Nelson’s navy to engage in an aggressive attack. Because the Royal Navy never allowed for the purchase of commissions, many officers came from a stratum of society which was desperate to secure their family’s position in British society. Men of royalty-cum-admiralty were perhaps less aggressive because they had more to lose. The execution of Admiral Byng in 1757 for failing to engage the enemy may have helped to stiffen the spine of the gentry serving in the Royal Navy. Leading up to the battle Nelson ordered that six ships be sent away to lure out Villeneuve’s fleet. The captains of those ships were devastated, not only would they miss out on the glory of battle, they would not be eligible to receive any prize money.

In England the officers of the navy came from a broad spread of English society, stretching from the lower reaches of the aristocracy through the landed gentry and professional classes to (occasionally) the genuinely poor. Of Nelson’s great predecessors in the 18th century, for example, Sir Cloudesley Shovell, who ran his fleet up on the rocks of Scilly, was the son of a Norwich merchant; Byng, who was short for cowardice off Minorca, was the song of a Kentish gentleman; Vernon was the son of a London merchant; Anson from Staffordshire gentry; Hawke the son of a barrister; Rodney from a family of army officers, and with his mother’s father a judge; Howe was the second son of an Irish peer; Lord Hood was the son of a vicar, like Nelson himself; Lord Barham’s father was a customs officer; St Vincent’s a lawyer; and Lord Cornwallis was the fourth son of a peer, who like his brothers had been educated at Eton. Those are the great men of the 18th-century navy. There is a drift towards high social status among them, but it is a far from exclusive set.

While income and wealth inequality today may mirror that of 19th century, there was at least an expectation that part of noblesse oblige was to put life and limb on the line for King and Country. In today’s professional armies casualty rates are expected to be inversely proportional to military rank. But in Nelson’s era naval officers were expected to be at an equal if not greater risk than their men. Officers were to be found on the deck of the ship where there was no sturdy oak hull to protect them from cannonballs and point-blank carronade fire. The risk of death was further heightened by the expectation that officers were to behave like “gentleman” which in this case meant wearing dress shoes into battle and being required to stand at all times even whilst their crews “hit the deck” when there was an incoming shot. One distinction between the British and French officer class was that the former was expected to understand practical details of sailing.

For the young French aristocratic officers … the curriculum they followed was essentially mathematical. They studied hydrology and the customs of the shipbuilding trade … but not history, nothing about fighting or sailing tactics. There were daily sessions set aside for both dancing and fencing. Any suggestions that French officer would know how to steer a ship, reef a sail, splice a warp or make a Single Diamond Knot, a Sprit-Sail Sheet Knot, a Carrick Bend, a Midshipman’s Hitch, a throat seizing, a mouse for a stay or puddings for yards, would have drawn as quizzical a look from him as it does from us.

Nicholson believes that Nelson embodied the shift in what constituted manliness from the 18th to the 19th century. The perfumed, voluptuous wigged male was replaced by a more dour and brooding aggressive masculinity. In literature, this can be seen in Pride and Prejudice with the contrast between Mr. Darcy and Mr. Digby. Supposedly the gentlemanly method of 18th century warfare, more akin to the quadrille, led to frequent but inconclusive battles. However Hawke had shown in the Seven Years’ War that decisive victories could be had if an admiral was willing to use aggressive and risky tactics.

The man of war, as complex as a clock, as large as a prison, as delicate as kite, as strong as a fortress and as murderous as an army, was undoubtedly the most evolved single mechanism, with the most elaborate ordering of parts, the world had ever seen.

Men of Honour is split into two parts: Morning and Battle. Each section has grand chapter titles like Zeal, Honour, and Humanity, with an accompanying entry from Dr. Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language. The Battle section of the book contains gruesome descriptions of how men were killed in the age of sail. There is one long and cringe-worthy passage that explains how a musket ball ultimately killed Nelson by forensically accounting for its path through his internal organs. By 1805 cannons and rifles had become powerful enough that at close range their effects rendered ships into abattoirs. Cannister and grape shot could be used to spray a deathly cloud of shrapnel into the enemy ship. Double-loaded cannonballs were used to blow the enemy hull to pieces. In military history combat distance if usually proportional to fire-power. Naval combat did not follow this rule at Trafalgar. For some of the French and Spanish ships, casualty rates were as high as 75%.

The intimacy of this battle meant that in some ships the muzzles of the French and English guns touched each other … In many ships more than 7,000 lbs of gunpowder was used during the engagement. What is extraordinary is not that people died or that ship structures were savaged but that anyone or anything survived.

Nelson’s heroic death at Trafalgar was a foundational element in the Victorian conception of war. Men of Honour’s historical footing is, ironically, strongest in describing the battle’s legacy in the last chapter. Throughout the 19th century a large portion of the British intellectual elite believed that in war men achieved “the highest sanctities and virtues of humanity”. If battlefields could be used to channel a country’s aggression and display its virtues then war could have a salubrious effect for the nation as a whole. It would take the charnel house that was the First World War to put paid to this belief. While Nicholson does a good job at describing the troubling legacy of Trafalgar, it is surprising that he has not noticed that his method of using “national character” to understand the past is one fallacies of historiography we are trying to move on from.

The shadow, or perhaps the light of Trafalgar, with its halo of courage, beauty and honour, its powerful and Elysian idea of the Happy Warrior, lasted only until the killing fields of industrial war … It was a brutal amalgam and it remains an inheritance with a troubling moral ambiguity at its heart.

Nelson's permanent monument in Trafalgar Square

-

Many Germans may have believed that conflict with communism was “inevitable” and the British were psychically scarred with trench warfare from the first world war. ↩