May reads (Book Reviews)

Book #1: Wicked by Gregory Maguire

In L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz the novel begins with Dorothy’s house being swept up in a tornado and happening to fall in the Land of Oz and crushing the Wicked Witch of the East. Treated a liberator by the locals, she is told that if she wants to return home she must journey along the yellow brick road and talk to the Wizard of Oz. In their meeting Oz offers to help Dorothy return to Kansas on the condition that she kill the Wicked Witch of the West. Dorothy and her compatriots are upset by the nature of the request, but they do not not question the moral legitimacy of their request for violence (the Witch is bad after all). But what were the underlying political realities that led Oz to request such an assassination? In Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, Gregory Maguire deftly constructs the world of Oz and tells the story of how Elphaba (the Wicked Witch of the West) comes to hold her position of power in the Vinkus (aka the land of the Winkies). Wicked is divided into five chapters, with the story of Elphaba’s upbringing in Munchkinlanders, her education in Gillikin, and her political rebellion in City of Emeralds. In the last two books In the Vinkus and The Murder and its Aftermath Elphaba embraces her witch identity and ultimately comes into conflict when Dorothy when she is given the shoes of the sister Nessarose (the Wicked Witch of the East).

“What shall we do now?” asked Dorothy sadly.

“There is only one thing we can do,” returned the Lion, “and that is to go to the land of the Winkies, seek out the Wicked Witch, and destroy her.”

At the time of Elphaba’s birth, Oz rules an imperial state. The previous indigenous ruler, the Ozma Regent, was overthrown in a coup by Oz. He maintains his power over the territories through the use of secret police the Gale Force. Elphaba’s father Frexspar is a priest in Munchkinland where he tries to teach the benighted locals the true word of the Unnamed God and of “unionism”. They are a difficult flock to manage. Frexspar has to constantly draw the Munchkinlanders away from the pleasure faith religions, Lurlinism, and various states of debauchery (orgies, binge drinking, etc). Many childhoods are difficult, but being born with green skin makes Elphaba’s miserable. She is feared and ostracised by the locals and her parents project their guilt on her. At the university of Shiz Elphaba becomes friends with many of the characters that will be present in the rest of the novel. During this time Oz begins to enact a series of legislation to strip Animals (the conscious animals) of their rights. Elphaba becomes the amanuensis of the goat Dr. Dillamond who is conducting research into the biological foundations of Animals. His work proves too political dangerous and he is assassinated leading to Elphaba’s radicalization. Through a series of unplanned events Elphaba eventually assumes the role of a powerful leader in the Vinkus region and her sister becomes the theocratic dictator of Munchkinland. After Nessarose is accidentally killed by Dorothy’s tornado-born house, Elphaba worries that her sister’s magic shoes may be used by Oz to attempt a reunification of Munchkinland. Her increasingly deranged pursuit of Dorothy and the shoes leads to Elphaba’s well-known downfall.

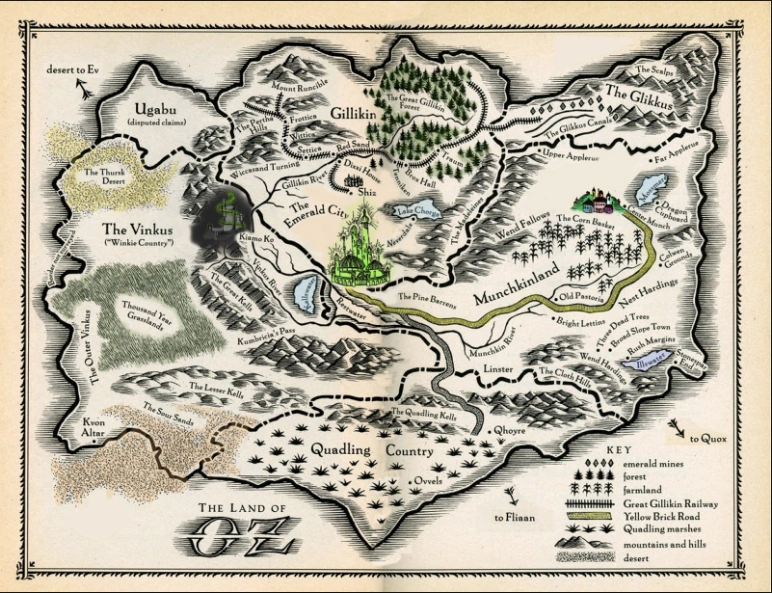

The Land of Oz

The writing in Wicked is excellent on many levels. The characters are vibrant and the dialogue is witty. The author strikes the right balance between world creation and accessibility. While not Game of Thrones, I enjoyed the political and cultural forces at play in the land of Oz especially around Animal rights and religion. Maguire’s vocabulary is immense and I found myself frequently looking up words like: ormolu, usufruct, bartizzan, palaver, sybarite, badinage, etiolated, and disport. The fourth wall is often broken with many references to our world including President Truman and Keats (“My silken flanks tarted up with garlands or the like”). The first three chapters are especially page-turners. Wicked is very much an adult’s fairytale story. Extreme violence is ubiquitous and life is cheap. The Oz world resembles the high middle ages or the renaissance, where there are some modern institutions (universities, stock exchanges) but political accountability is non-existent. Magic or no magic, Wicked does a fantastic job at showing how the calculus of power works and its impact on politics and culture. Maguire’s first book in The Wicked Years is a masterpiece.

Book #2: Leading Change by John P. Kotter

As someone who works in the field of data science I have often seen institutions express the desire to embrace “big data” and “machine learning” into their organization. However creating a data-friendly and literate culture often proves quite challenging. I started Leading Change by John Kotter as to see how management theory understood the principles of change leadership. Kotter notes that firms usually fail to implement meaningful changes because of complacency (e.g. not enough urgency to change). Pushing people out of their comfort zones goes against the grain of human nature. Alternatively if you push too hard, you may end up instilling a sense of anxiety rather than urgency and people will retreat even more sharply into their foxholes. The book identifies eight common mistakes that institutions make when trying to adopt meaningful change such as underestimating the power of vision, failing to create short-term wins, and declaring victory too soon.

To match the eight no-nos, Kotter also outlines an eight stage process to establish major change: 1) creating a sense of urgency, 2) creating the guiding coalition, 3) developing a vision and a strategy, 4) communicating the change vision, 5) empowering broad-based action, 6) generating short-term wins, 7) consolidating gains and producing more change, 8) anchoring new approaches in culture. The order of these steps matter and many people try to short-circuit the necessary preliminaries and jump straight to step 5 (e.g. by hiring or firing people).

The book identifies the useful distinction between management and leadership. The former is about planning, organizing, budgeting, and problem solving within a large organization. At the turn of the 20th century there was a dearth of managers who could help run the thousands of new firms that were being created in capitalist economies. This supply imbalance was what led to the creation of business schools and their implicit mandate remains largely unchanged today. Management at its best delivers predictability and order to consistently deliver short-term results. However leadership is different, it is about direction, vision, and aligning and inspiring people. Unfortunately most organization’s instinct it to manage change rather than leading it.

While I found the first several chapters interesting I was not able to get into this book. It lacked concrete examples or statistics. There is a certain way of writing for the Harvard Business Review that Leading Change perfectly encapsulates that I find makes the reading experience dull and monotonous. Overall this book may be interesting to someone in an executive position actually trying to affect change, but it will likely have little appeal to the common reader.

Book #3: The Magic of Saida by M. G. Vassanji

M. G. Vassanji is vying to become one of my favourite fiction writers along with Orhan Pamuk and Italo Calvino. These authors share an important literary technique: repetition on a theme. The plots in most of Vassanji’s work centre on Indians that have a mixed identity as either East Africa Indians or immigrants to the New World. Questions of identity, belonging, and place underpin the existential questions that the characters are grappling with. I first read The In-Between World of Vikram Lall and was floored by the beautiful prose and richly developed characters. Whereas Lall is set in Kenya (where Vassanji was born), The Magic of Saida takes place in Tanzania (where Vassanji grew up). Lall deals explicitly with the political challenges African Indians faced in post-independence Kenya. While political turmoil is an ever-present theme in the background of Saida, it is Tanzania’s conflicted colonial history that truly weighs on the characters and their sense of identity. Vassanji has a charming ability to channel the voices of history through narration.

Tens years after the Kilwa hangings, a rumour began to be heard: There is this man. In the Matumbi district, eti. In a village called Ngarambe. He entered the water for a whole night and when he came out he was possesed by the spirit. Kinjikitilé. Enh-heh, that’ his name, this mganga. He is the one with the dawa and the spells. Bokero, Hongo–these are also his names. He will spray you with the magic water with a branch; or he may make you drink it, or pour it on your head. He will tell you what to do. And then? These Germans–nothing. They will go. How? Their guns, their bullets–nothing. How, nothing? They will fire, pe-pe-pe! but their bullets will turn to water with this magic. Soft as rainwater, and then we will fight them. But the time is not now. The water is travelling through the country.

In the 1880s the European powers decided to carve up the African continent in an “orderly” way in order to avoid great power conflict stemming from colonial competition (alongside many other political and economic motivations of course). Germany established a major colony in East Africa in 1885 which today would comprise of modern Tanzania, Kenya, and Rwanda. But long before the Germans, the Swahili Coast has been the site of foreign trade for more than a millennia with the monsoon winds allowing for sailors to reach the coast all the way from Indonesia. Examples of other influences include the Omani Sultan of Zanzibar who ruled over a large portion of the coastline and used African slave labour to establish a plantation economy, Indian merchants who were in constant competition with Arab traders for centuries, and the Portuguese who held onto many trading posts throughout the age of exploration. If not exactly cosmopolitan, the Swahili coast could at least be said to be globalized.

The Swahili Coast has a long history of trade and colonization

The main character of The Magic of Saida, Kamal Punja, is born in the ancient city of Kilwa in British Tanganyika to an African mother and a Indian father. To the Indian community Kamal appears to be a dark-skinned African with curly hair. Because of his outside “Indian option”, his African neighbours are sceptical of his native bona fides. Raised by his mother, as a boy Kamal becomes an admirer of the Swahili poet Mzee Omari who is the grandfather of his childhood friend Saida. Mzee’s celebrated verse exalts the historic Tanzanian resistance to German occupation from the brave Chief Mkwana to the spiritually possessed Kinjikitile. Most readers (including myself) are probably unaware of the German empire’s viscous colonial wars including the suppression of the Maji Maji Rebellion. As the novel progresses we learn that even in Tanzania’s early colonial history identity and loyalty were not so easy to establish. Kamal’s mother comes from a people that were routinely enslaved by Mkwana’s tribe and Mzee Omari actively collaborated with the Germans when they were in power.

The ancient fortress of Kilwa

Kamal’s African phase soon gives full to full Indianizaztion when he moves to Dar es Salaam to be raised by his Indian uncle after his mother gives him up so that he can have a better life. Information is often withheld from Kamal. He is never told why his father left, why his mother gave him up, and when he ultimately returns to Tanzania, where Saida has gone to. Not only is Kamal detached from where he inhabits, it sometimes feels as though he never fully connects with anyone. As he grows older and becomes a successful doctor, Kamal is haunted by his memory of Saida. Before leaving to study medicine at Makerere he plights to Saida his troth that he will one day return to Kilwa and marry her. But Kamal soon finds himself engaged to an Indian woman and offered a chance to move to Canada during Idi Amin’s expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972. Events seem to happen to Kamal and the narration of his life comes across as though it were a story. There is often little sense of agency, and like his admiration for problematic Tanzanian freedom fighters, Kamal acknowledges that he understands why some Africans are happy to see the Indians expelled.

Life in Edmonton provides Kamal with financial success undreamt of in Tanzania. But after stumbling upon a book about Kilwa at a book store he develops a mid-life passion to rediscover his roots. As his children grow up and his marriage falls apart Kamal seeks out the one person who may still be able to provide him with a feeling of catharsis: Saida. In Kilwa he is greeted with hostility and suspicious by the locals who are unsure of his motivations. They challenge him with questions that Kamal has struggled to answer his entire adult life. Why did you leave? Why did you treat rich Canadians when there are so few doctors in our country? Why do you care so much about Saida if you did not marry her? But Kamal is also critical of Tanzanians. He remembers a proud nation after independence that now seems ready to give up its dignity for foreign aid. Where has the sense of self-sufficiency and Ujamaa gone? Kamal’s search for Saida is ultimately a failure and his story ends without closure. But for the reader it is Kamal’s journey and Vassanji’s beautiful prose that is all the magic we need to enjoy the book.