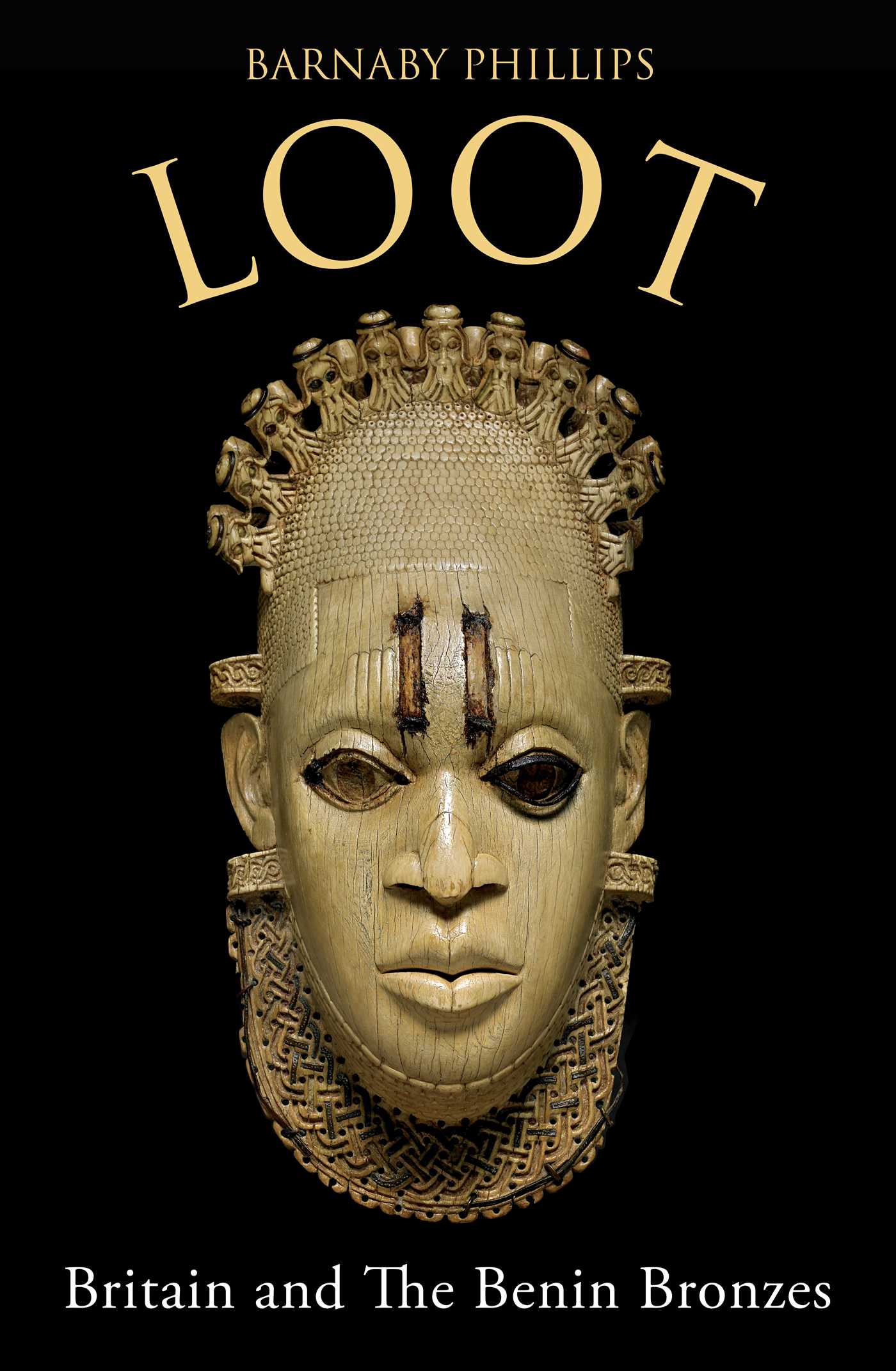

Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes by Barnaby Phillips (Book Review)

I have become accustomed to my book purchase recommendations being politely declined by my local library. There is only so much room on the stacks for a monetary history of China, alas. I was therefore pleasantly surprised when my request for Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes by Barnaby Phillips to went throught. As the title suggests, Loot explores the history of the Benin Bronzes from their ancient origins to their theft by the British during the 1897 punitive expedition against the Kingdom of Benin.

For the last 125 years, the punitive expedition of 1897 has been the defining historic event for the Edo people of modern-day Nigeria. In British history textbooks the expedition is a footnote in an increasingly embarrassing colonial history. In recent years the Bronzes have become a flashpoint between the rich museums of the West, which are hesitant to set a precedent of returning colonial artefacts, and the ancestors from whose people the artworks were originally stolen. As English-speaking societies continue to go through a “Great Awokening,” books like Loot provide a useful background in understanding the motivations driving the decolonization and anti-racism movements.

History

The Benin Bronzes are beautiful pieces of art. Like the Elgin Marble friezes, they depict a variety of heroic and regal characters in a naturalistic style. Unfortunately, outside of the art world and Nigeria (of course), the Bronzes are barely known. This is beginning to changing however. Demands for the decolonization of Western institutions and art restitution are putting the Bronzes, are other pieces of ethnographic art, in the spotlight in a way they have never been before. Why do the great works of art of the Edo people live in London and Berlin? And why do European artists like Damien Hirst receive more attention for their copies of the Bronzes while the original works remain unknown? These are the sorts of questions that are increasingly being asked of museum curators who would prefer the attention was focused elsewhere.

Despite their name, the Benin Bronzes are actually made of a copper alloy. The “Bronzes” were produced over a 600 year period, dating from creation of Igun Eromwon (The Guild of Bronze Casters) by the Oba Oguola in 1280 until the destruction of Benin City in 1897. Metallurgy has a long and proud tradition in West Africa. For instance, the city of Kano in northern Nigeria was named after a blacksmith, and it has an impressive history of skilled metallurgists.

Debate continues as to the origin of the Benin Kingdom and its casting tradition. Claims that the Kingdom of Benin was founded by the offspring of the Ooni of Ife are politically contentious. When the Portuguese arrived in the 15th century, the Kingdom of Benin had already absorbed many of its neighbours and Oba lived in a substantial palace within a walled city. The Portuguese presence to the Oba proved to be a boon, both militarily and artistically. A single Portuguese ship could carry thousands of manillas which could be melted down for copper, bronze, and brass. The Igun Eromwon now had a surfeit of material to work with. In exchange for slaves, the Benin Kingdom would use the fearsome weaponry of the Europeans to subdue their enemies and expand their influence.

By the time British established hegemony over the region of Nigera, the golden era of the Benin Kingdom had long since passed. The Obas had become increasingly jealous of their privileges and felt (rightly) that British law and Christianity were threats to their hold on power. In January 1897 the acting Consul General of Niger Coast Protectorate, James Robert Phillips, made an unauthorized expedition to Kingdom of Benin to demand the resignation of Oba Ovonramwen. Phillips had lost patience in the Oba’s mercantilist policies and refusal to open up his kingdom to free trade. The plan was to have a native council of indigenous elites friendly to British interests step in for the Oba.

Two months before his ill-fated expedition, Phillips had sent the Foreign Office a message explaining his rationale for regime change. But he grew tired of waiting for a response and decided to sally forth on his authority alone. News of Phillips impending visit caused panic in the Oba’s court. A powerful faction demanded that the Kingdom strike while they were still in a position to do so. The order was given to attack Phillips’ expedition, and his small band of Europeans (a dozen) and African porters (hundreds) were ambushed and slaughtered. Two Europeans were able to escape the attack and sailed down the Ughoton Creek with the help of friendly tribes until they reached a British outpost.

The news of the Consul General’s murder sent shock waves through the British colonial establishment. Within a week of his Phillips’ death it was decided that a punitive expedition would be sent to remove the Oba and destroy his Kingdom once and for all. Overnight Phillips had gone from a loose cannon disregarding official orders to a martyr for civilization.[1] By February 9th the British had landed troops in Nigeria and by the 18th they had captured the capitol and deposed the Oba. It was a lightening war whose speed and success surprised even the British.

When the British marched into Benin City in 1897, there were no international agreements in place as to the laws of warfare.[2] Those informal rules that did exist were limited to “civilized warfare”, and were hence not in effect for a colonial campaign like Benin. British officers went to work and systematically looted anything they found in the city that looked like it could be of value. In the late 19th century the most valuable commodity in Africa was ivory, and the Oba’s palace was full of it. Grand tusks with intricate carvings were considered to the prize pickings. The Bronzes, while less valuable than ivory, were clearly of great artistic value. Even if an officer did not fancy the bas relief, he could always gift it to the British Museum later (and many did).

Did any of the officers who engaged in the looting feel guilty about their theft or wonder how it aligned with their professed goal of spreading British justice and the common law? Victorians were master compartmentalizers who excelled in avoiding a sense of guilt or wrongdoing. To the British officer, the Oba was a petty tyrant who engaged in barbarous practices like human sacrifice. His Kingdom still maintained a system of slavery and “fetish” worship which was an obstruction to human progress. It could hardly be considered a great loss that beautiful relics, perhaps even made by the Portuguese, should be taken to England where they would be far more appreciated.

After fleeing the city, the Oba was eventually found and exiled to Calabar where we would die some 17 years later. While the loss of their government, king, and centuries of artistic achievement was a terrible psychic blow the Edo, the worst had yet to come. Shortly before the British were ready to depart, a tremendous fire started that would destroy most of Benin City. Although many Edo people believe the British deliberatively destroyed the city, the documentary record indicates that the British high command, at least, saw the fire as an unfortunate and unplanned event. Not for the human cost of course, but because much loot was lost in the conflagration. Most of the art in the Oba’s palace was part of shrines or installations. The destruction of the palace meant that the looted Bronzes and ivory art pieces would be forever unmoored from their original spiritual setting.

Although loot was considered fair game when taken from “primitive” peoples, there were some Europeans who expressed concern at their armies’ artistic vandalism. After the British destroyed Maqdala in 1868 and looted many of its treasures, Prime Minister Gladstone expressed his consternation about it several years later:

He (Mr. Gladstone) deeply regretted that those articles were over brought from Abyssinia, and could not conceive why they were so brought. They were never at war with the people or the churches of Abyssinia. They were at war with Theodore, who personally had inflicted on them an outrage and a wrong; and he deeply lamented, for the sake of the country, and for the sake of all concerned, that those articles, to us insignificant, though probably to the Abyssinians sacred and imposing symbols, or at least hallowed by association, were thought fit to be brought away by a British Army.

In September 1897 the British Museum held an exhibition in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The Museum and its curators were prescient in acquiring as many Bronzes as possible from returning officers. Visitors who saw the African sculptures were amazed; the castings resembled “the finest bronzes of the fifteen and sixteenth centuries in Europe.” Because Africans were considered to be genetically inferior peoples without a history, the presence of the Bronzes implied that either the Edo people had not made them or that African history was need in of revision. The “problem of the origin and meaning of the Benin Bronzes” was one for Europe and not for Benin to solve. For Felix von Luschan of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin the Bronzes were “purely African, thoroughly and exclusively of and out African.” He was shocked that the British treated the castings as little more than war booty. In his more enlightened moments, Luschan even though that “the culture of the so called ‘savages’ is not inferior to our own, only different.”

Even though the Bronzes did not immediately cause a fundamental shift in ideas of racial superiority, they did at least provide an observational counterpoint to claims that Africa was without a history. In the early 20th century artistic elites like Picasso and Gauguin used the flood of exhibits showing art taken from colonial outposts as the basis for a new artistic movement: Primitivism. Inspired by art from Africa and Oceania, this movement used the exoticism of indigenous cultures as a mechanism to explore more abstract and conceptual art pieces. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon has mask-like faces redolent of the Bronzes themselves. While claims that the Bronzes were the catalyst of this movement are overstated, they where a contributor the shift in European artistic sensibilities.

Rightful owners

The spoils of war and the restitution of art is not a modern consideration. Islamic military law dictated (in theological theory) what could and could not be looted after a siege. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, the forces of the Seventh Coalitions collected most of the artwork that Napoleon’s Grande Armée had stolen and returned it to their countries of origin. As Duke of Wellington wrote to Lord Castlereagh in 1815:

They would desire to retain these works of art, not because Paris is the properest place them to be preserved in … but because they have been acquired by conquests of which they are trophies. The same feeling that makes the people of France wish to keep the pictures and statures of other nations, must naturally make other nations, now that victory is on their side, to restore those articles to their lawful owners; and the Allied Sovereigns must feel a desire to promote this object… In my opinion, it would not only be unjust in the Sovereigns to gratify the French people, but the sacrifice they would make would be impolitic, and it would deprive them of the opportunity of giving the French a great moral lesson.

The justification for the return of the Benin Bronzes is a strong one. The descendants of the Oba and the Edo people are still around today and haven’t gone anywhere in the last 125 years. The great-great grandson of the Ovonramwen, Ewuare II is the current Oba of Benin. Unlike the Koh-i-Noor, it is actually quite clear who the artefacts should be returned to.

While not in living memory, 1897 was not that long ago. There is a complete consensus that art stolen by the Nazis should be returned to the descendants of Jewish families. The second world war a little more than 40 years after the Benin expedition. If art restitution applies to European war crimes committed in Europe, should it not also apply to those committed in Africa? The obvious difference is that of race. Another important difference is that of players involved. The Nazis were bad, and the Allies were good. So anything the Nazis stole was inherently a bad thing. In contrast, Oba Ovonramwen and the Benin Kingdom hardly outranks the British of 1897 in terms of moral superiority.

There was an arguable justification for Phillips move to depose Oba Ovonramwen. Even for his time, Ovonramwen was a stultifying and reactionary king. Human sacrifice, while surely exaggerated by the British for political reasons, was a true and deranging fact of life. The Edo people were completely illiterate. Poverty was widespread and trade was strictly controlled to maintain political power. Arbitrary punishment at the whim of the Oba was common, even for powerful Edo families. The British destruction of old Benin’s brutal political system had the possibility to be a blessing. Does contemporary horror at the old Benin regime give any moral legitimacy to Western museums to keep their collections? I do not think so. But it does highlight that the political elites who were victims of European colonization were as brutal as their colonizers, if not more so.

As part of the research for this book, Barnaby Phillips talks to a wide range Nigerians about the restitution of the Bronzes. Many are surprisingly circumspect in their assessment as to whether the Bronzes would be better situated in Benin City as opposed to the British Museum. To be clear the overwhelming majority of Edo people want the Bronzes back. They are just more resigned to the fact that Nigerian institutions will almost certainly be worse stewards of Edo cultural identity. The pieces have also been gone for so long that they have become somewhat alienated from Edo culture. Furthermore, many devout Christian Yorubas now see the Bronzes as symbols of idolatry and fetish worship.

Wrapped up in this discussion is Nigeria’s complex relationship with its history of colonialism. Most Nigerian politicians and public figures will express the view that British colonialism was an unalloyed disaster; responsible for most, if not all, of the country’s problems. Yet examining the specific details of British colonialism and its institutions is deliberately avoided when such comparisons might draw forth uncomfortable similarities with the present day. Amazingly, from 2007-2019 Nigeria’s government removed history class from the public school curriculum. Since the Biafran civil war, the country’s elite have operated on the principle that some level of historical ignorance is necessary for national unity.

Some private citizens have already begun to hand back their Bronzes. Mark Walker was the grandson of a British officer who inherited two small Bronzes. In 2014 he flew out to Benin City and presented the items as gifts to the Oba at a highly symbolic ceremony with a packed audience. Yet this highly successful public display of goodwill was almost derailed by the federal Nigerian government which tried to have Mark present the Bronzes as gifts to the Minister of Arts and Culture in Abuja. Mr. Walker wisely refused to give the Bronzes to anyone but the Oba. The incident highlights the tension that will almost certainly emerge between the Oba, who has almost no official political power, and the federal and state governments of Nigeria were a substantial number of Bronzes to be returned.

Nigeria’s museums do not have a good track record when it comes to managing the nation’s cultural treasures. It is an uncontroversial view that most Nigerian institutions began disintegrating in the 1980s when the price of oil collapsed. By the 1990s art was becoming routinely stolen from Nigeria’s museums. In 1996 the Minister for Culture said that Nigeria was “losing our cultural heritage at such an alarming rate that unless the trend is arrested soon, we may have no cultural artefacts to bequeath to our progeny.” Nigeria’s leaders have historically viewed museums more as personal warehouses than as national treasuries. In 1961 Prime Minister Belawa took a tusk from the national museum to give to President Kennedy. In 1973 Yakubu Gowon dropped into the national museum to find a gift for Queen Elizabeth for his upcoming visit to England. A former Nigerian civil servant put the absurdity of the situation well: “It shows the level of ignorance of our rulers. You can’t give away a nation’s treasure to make yourself look good before another ruler.”

While Gowon and company might have been stealing the nation’s patrimony, many didn’t notice because of the tremendous oil revenues that were pouring into the country. When the Festival of Arts and Culture was held in Lagos in 1977 (FESTAC 77), post-independence Nigeria was at its zenith in cultural self-esteem. Lagos was often at a standstill during the festival as the entire city participated in the exhibitions, concerts, and plays. The Nigerians had planned on making the Queen Idia ivory mask the symbol of the festival. Unfortunately for the FESTAC organizers, the British Museum was not willing to send her.[3] The whole incident was the first time the Benin Bronzes and their restitution (or lack thereof) had garnered international attention. Nigerian and pan-African opinion was clear, the British were unreformed criminals who deserved to be hauled before the International Criminal Court.

One interesting consequence of the FESTAC blow-up of 1977 was that it highlighted that complex relationship between Britain’s national interests and the autonomy of the British Museum. The Foreign Office put meaningful pressure on the Museum to give over the mask. If the Nigerians wanted an old and fragile relic so be it. The government of Britain was more concerned about its balance of payments crisis, access to railway contracts, and oil rights in the country. The Trustees of the British Museum were indifferent to these political considerations and saw their role as purely stewards of art. In the end the Nigerian government commissioned five Benin artists to make copies of the mask. To this day Joseph Alufa, one of those artists, is still waiting to be paid for his work.

Restitution

Shortly after his election in 2017 President Macron announced that he would set up a commission to look into the best course of restitution for the numerous pieces of African art that are in French museums. The commissioned Sarr-Savoy report was a bomb shell in the art world. The report said that France should give back “any objects taken by force of presumed to be acquired through inequitable conditions.” Three years after the report, France has only returned 26 objects stolen from the Palace of Abomey back to the country of Benin (not to be confused with the Kingdom of Benin).

While France was the first mover, many other Western museums have begun to return some art pieces to their countries of origin. The rate of repatriation is low however. In 2018 Germany’s Cultural Minister released guidelines for museums to deal with artefacts acquired during the country’s colonial era. This mainly means giving money to students to do research on ethnographic pieces of art and a formal restitution claim process. Perhaps the German’s extensive experience with the German Lost Art Foundation for dealing with Nazi-era cultural thefts will eventually lead to a more systematic approach. The UK Arts Council and the National Museum of the Netherlands have also adopted similar protocols to the Germans.

While significant returns of art pieces have not been forthcoming, there have many news headlines of ad hoc restitutions. The German Historical Museum gave back a stone cross to the Namibians as well as skulls of Herero genocide victims. The Quai Branly, which has most France’s ethnographic artworks, returned the sword of a deposed Senegalese leader. Demands for the return of stolen art will likely become the norm for Western institutions in their dealings with former colonies. Even within developed countries, there is a growing pressume from indigenous groups to return stolen artefacts. For example, in Canada, there is a strong demand that the Vatican return indigenous art pieces as part of the truth and reconciliation process.

For Western museums there is a glaring irony that the overwhelming majority of ethnographic artworks, including the Benin Bronzes, are hidden away in storerooms. The amount of artwork on display at most museums will be, at most, 1% of their collection. For example, the British Museum has a quarter of all Benin Bronzes (700) in the world, but no more than 100 will ever be on display at one time. Were the Museum to permanently repatriate 80% of their Bronzes, the viewing public would probably be unable to tell the difference. Yet even if the trustees of the British Museum wanted to repatriate a significant share of their collection, there are legal constraints as the British Museum Act prevents the institution from disposing of any its holdings.

Concluding thoughts

I assume that most of the professed concern around social justice, anti-racism, and intersectionality is a public relations exercise by large institutions to limit their accountability and engage in costless signalling. There is strong reason to believe that the sincerity of a professed belief is inversely proportional to the political power a person holds. That is why I find the issue of art restitution so interesting because it requires an actual sacrifice on behalf of “woke” institutions and governments. Will Western countries be willing to take a write-off of their most valuable treasures? Will private collectors hand over multi-million dollar art pieces of art to a Nigerian king?

In the long-run I suspect the answer is no. Instead, accommodations around “access” will be made. Perhaps the British Museum will constantly have a large share of its Bronzes on display in Benin City at any one time. Yet it will always be clear that this is a loan. I might be too cynical, but actions always speak louder than words. In fact, talk isn’t just cheap, it’s almost free.

For Benin, the British invasion will always represent the moment … the ‘world turned upside down’. For Britain it was another small campaign against a primitive tribe on the frontier of Empire, of little consequence after the brief thrill of victory. It’s perhaps not surprising that the children of those who toppled the Oba and took his treasure should have been oblivious to those events. The winners get to write history. Often that means forgetting its less convenient chapters.

-

A few days after Phillips’ death, a telegram finally came from London informing the former Consul General that he was not engage in an attempt of regime change with the Oba. ↩

-

This would change two years later with the signing of the 1899 Hague Convention. ↩

-

Although the museum could of course send a replica. ↩