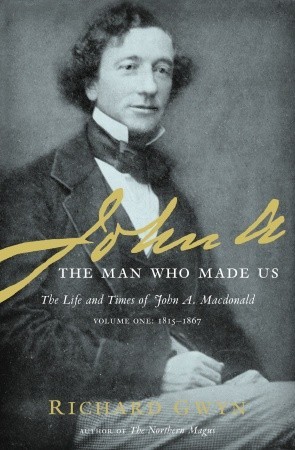

John A by Richard Gwyn (Book Review)

John A: The Man Who Made Us is the first volume of Richard Gwyn’s comprehensive biography of Canada’s first prime minister. Though books on Sir John A abound, Gwyn’s accessible account of his life is seen a predecessor to the two volume work of Creighton in the 1950s. This first volume tells of Macdonald’s rise to political prominence and ends just after Confederation in 1867. Born in Glasgow in 1815, Macdonald arrived in Upper Canada at the age of five when his family decided to emigrate to the New World in order to escape Hugh Macdonald’s bad debts.

Despite the famous quip accorded to Samuel Johnson by Boswell that “the noblest prospect which a Scotchman ever sees, is the high road that leads him to England,” the Macdonald family landed in an area of British North America that was, if not exactly run, then heavily influenced by the Scottish émigrées that had already settled there. Though his father Hugh was a lousy businessman, the family at least ensured that enough money could be found to send John to grammar schools which set him on a course for legal training. The family’s Scottish pedigree proved essential in Sir John’s early years by getting him an apprenticeship with Kingston’s most prominent lawyer.

The crucial introduction to Mackenzie had come to Macdonald as a gift from the family’s patron, Colonel Macpherson…

Like a good Scot, Macdonald was always practical and never dogmatic. He jumped between commercial and criminal law and represented a motley case of the criminally accused. Gwyn argues that Macdonald’s pivot to criminal law was a way to build a public persona before starting a political career.

“I am satisfied to confine myself to practical things… I am satisfied not to have a reputation for indulging in imaginary schemes and harbouring visionary ideas… always utopian and never practical.”

Macdonald was certainly not the only Scot or lawyer amongst the Fathers of Confederation.[1] One consequence of having a country founded by lawyers is an enduring legacy of a commitment to the rule of law. There are few countries where the defining political scandal of a government would centre around the Shawcross principle.

During the 1865-66 invasions of Canada by Fenians, or Irish Americans, public pressure developed for individuals to be arrested on mere suspicion of supporting the Fenians. Macdonald rejected the demands: “This is a country of law and order,” he said, “and we cannot go beyond the law.”

Depending on your perspective Macdonald either discovered the inevitable, or brilliantly pioneered, the art of governing Canada. This included a few key ingredients. First, one must be on good terms with French Canada. Even if you don’t win a majority of seats there, French-Canadian MPs are a numerical (and moral) requirement for a governing party. Second, shamelessly use patronage and government favour to smooth over regional grumblings. Lastly, pick on the Americans.

Macdonald and McGee disagreed on the way Canada could best accommodate itself to the challenge of living and surviving beside a colossus. McGee was now calling for a “a new nationality,” or for common social and cultural characteristics that would make Canadians a distinct people. Macdonald’s solution was more narrowly political: Canada should remain as British as possible. This disagreement was about means, not about the end they sought… Politically they were both anti-Americans… before Macdonald, lots of Canadians had disliked and feared the United States, but none, like him, raised it to the level of his principal political policy. What is really striking about Macdonald’s anti-Americanism was that the overwhelming majority of Canadians agreed with him.

One hundred years after the French were defeated on the Plains of Abraham in the Seven Years War many French-Canadians still took their pledge of loyalty to the British crown to heart. Though the British promised language and educational rights to their conquered subjects, it was clear the the English crown would always be seen as foreign. Monarchism may have divided English and French Canada, but it was clear to Canadiens that an American absorption of British Canada would certainly be a worse fate. Anti-Americanism was therefore a political force that could be shared equally between the English protestants and the French Catholics.[2] To Her Majesty’s loyal subjects the American Revolution was viewed as an act of disloyalty rather than a cry for freedom.[3]

More generally politics mirrored the landscape of Canada in the 19th century: it was a wilder time. Macdonald has to be arrested by the Sergeants-at-Arms when he was in Legislative Assembly in the Province in Canada in 1849 to stop him from carrying out a duel with Edward Blake. The era’s politics was generally raucous, but, also had its sweeter moments. Since founding The Globe in 1844 George Brown had been a political thorn in Sir John A’s side. Brown, a fellow Scot,[4] was as much of a Whig as Macdonald was a Tory. Their personality differences matched their politics with Brown’s intensity and humourlessness contrasting to Macdonald’s easy-going manner and sharp wit.[5] By 1864 the Legislative Assembly had become paralysed by gridlock and the need for a federal union was becoming increasingly clear. The two men put aside their personal hatred for each other and formed the Great Coalition which was the last government of Canada before Confederation.

Macdonald revealed that the opposition member he was negotiating with was the “member for South Oxford” – Brown. There were gasps of disbelief… The chamber rang out with cheers, shouts, exclamations, slaps on the back. The Canadien newspaper expressed its opinion that the Macdonald-Brown accord “comptera parmi les plus memorable de notre histoire parlementaire.”… It was the most dramatic instance of political reconciliation in Canada’s parliamentary history since 1848, when Governor General Lord Elgin had followed his reading of the Throne Speech in English, with, for the first time, a re-reading in French.

Though written barely a decade ago (2008), if Gwyn were writing this book today he would have to go about it differently. In the last few years the public criticisms and push-back against Sir John’s legacy have reached a boiling point due his toxic legacy with First Nations in Canada. Métis-Canadians have a particularly painful history with Canada’s first prime minister as he oversaw a brutal suppression of the North-West Rebellion and ensured Louis Riel was executed. Métis activists are hardly the only Canadians trying to remove his statues. Sir John has also been credited with being the architect of Canada’s residential school system which is seen as one of the country’s most destructive and shameful acts carried out against First Nations and has been condemned as a policy of cultural genocide. Left-wing activists are now actively vandalizing his statues across the country. Even Scotland had distanced itself from one its most successful exports. I am interested to see how Gwyn will handle these historical moments in his second volume which I intend to read.

Biographers are often accused of developing a soft spot for the subject of their writing. In Gwyn’s case the author indicates his partiality in the subtitle of the book. This is history in the triumphalist manner of Berton: the long arc of history bend towards Confederation. The book could have also spared the reader from many tangential footnotes that came across as marginalia from a Wikipedia article. I suspect a more critical biographer would have pushed back against the idea that Macdonald was the only possible man to lead the country. And though I am sympathetic to it, was the country’s defiance or American absorption the right choice given the economic costs it has imposed on the country since Confederation? It is not easy though to write engaging Canadian history and Gwyn must be credited for this. His pleasure of researching and writing about Sir John comes through the text and the reader can’t help but absorb some of his enthusiasm.

-

Out of the 36 of them, more than half were Scots and 19 were legally trained. ↩

-

As Taché, one of Canada’s Fathers of Confederation, put it: [T]he last cannon which is shot on this continent in defence of Great Britain [will be] fired by the hand of a French-Canadian. ↩

-

Note that today Canada’s only hereditary title is that of “UE” (Unity of Empire) for those descendants of the United Empire Loyalists. ↩

-

Although Brown was born in Edinburgh rather than Glasgow, which perhaps helps to explain some of men’s animosity towards one another. Recall the famous quip that the best thing to come out of Edinburgh (Glasgow) is the train from Glasgow (Edinburgh). ↩

-

Macdonald’s most famous remark about their rivalry was that “[the public] would rather have a drunken John A. Macdonald than a sober George Brown.” ↩