Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino (Book Review)

A weary Kublai Khan sits in his garden and asks of Marco Polo to tell him of the cities of his empire he will never visit. Polo describes to him fifty-five cities he has seen – each strange and fantastical – cities whose properties are not by bound either physics or time. While being a slight parody on the Travels of Marco Polo, the cities we learn of from Polo in Invisible Cities are not just meant to be caricature of the confabulations of medieval travel literature but a deeper reflection of the nature of memory, space, and time.

Kublai is instantly drawn to Marco, even if at first the latter cannot speak his language.

Marco Polo could express himself only with gestures, leaps, cries of wonder and of horror, animal barkings or hootings, or with objects he took from his knapsacks–ostrich plumes, pea-shooters, quartzes–which he arranges in front of him like chessmen… Newly arrived and quite ignorant of the languages of the Levant, Marco Polo cold express himself only by drawing objects from his baggage–drums, salt fish, necklaces of warthogs’ teeth–and pointing to them with gestures, leaps, cries of wonder or of horror, imitating the bay of the jackal, the hoot of the owl.

At first in a dark mood, the great Khan thinks poorly of his empire.

…an endless, formless ruin, that corruption’s gangrene has spread too far to be healed by our sceptre, that the triumph over enemy sovereigns has made us the heirs of their long undoing.

The great Khan hopes to hear of stories, pockets of health, that will provide some relief to this pessimistic view. Or perhaps the seeds of Polo’s stories will germinate into a new empire.

Kublai: Your cities do not exist. Perhaps they have never existed. It is sure they will never exist again. Why do you amuse yourself with consolatory fables? I know well that my empire is rotting like a corpse in a swamp, whose contagion infects the crows that peck it as well as the bamboo that grows, fertilized by its humours. Why do you not speak to me of this? Why do you lie to the emperor of the Tartars, foreigner?

Marco: Yes, the empire is sick, and what is worse, it is trying to become accustomed to its sores. This is the aim of explorations: examining the traces of happiness still to be glimpsed, I gauge its short supply. If you want to know how much darkness there is around you, you must sharpen your eyes, peering at the faint lights in the distance.

What do each of these cities represent? At first blush it is difficult to infer given how wild they each seem.

In Maurilia, the traveller is invited to visit the city and, at the same time, to examine some old post cards that show it as it used to be: the same identical square with a hen in the place of the bus station, a bandstand in the place of the overpass, the young ladies with white parasols in the place of the munitions factory. If the traveller does not wish to disappoint the inhabitants, he must praise the postcard city and prefer it to the present one, though he must be careful to contain his regret at the changes within definite limits: admitting that the magnificence and prosperity of the metropolis Maurilia when compared to the old, provincial Maurilia, cannot compensate for a certain lost grace, which however, can be appreciated only now in the old post cards, whereas before, when that provincial Maurilia was before one’s eyes, one saw absolutely nothing graceful and would see it even less today, if Maurilia had remained unchanged; and in any case the metropolis had the added attraction that, through what it has become, once can look back with nostalgia at what it was.

In the centre of Fedora, that grey stone metropolis, stands a metal building with a crystal globe in every room. Looking into each globe, you see a blue city, the model of a different Fedora. these are the forms the city could have taken if, for one reason or another, it had not become what we see today. In every age someone, looking at Fedora as it was, imagined a way of making it the ideal city, but while he constructed his miniature model, Fedora was already no longer the same as before, and what had been until yesterday a possible future became only a toy in a glass globe.

Adelma, the city of the dead:

You reach a moment in life when, among the people you have known, the dead outnumber the living. And the mind refuses to accept more faces, more expressions: on every new face you encounter, it prints the old forms, for each one it finds the most suitable mask. Perhaps Adelma is the city where you arrive dying and where each finds again the people he has known.

The city of Leonia refashions itself every day: every morning the people wake between fresh sheets, wash with just-unwrapped cakes of soap, wear brand-new clothing, take from the latest model refrigerator still unopened tins, listening to the last-minute jingles from the most up-to-date radio.

All of which has led a city of a gargantuan garbage pile ready to imperil the city.

[A] landslide looms: a tin can, an old tire, an unravelled wine flask, if it rolls toward Leonia, is enough to bring with it an avalanche of unmated shoes, calendars of bygone years, withered flowers, submerging the city in its own past, which it had tried in vain to reject, mingling with the past of the neighbouring cities, finally clean. A cataclysm will flatten the sordid mountain range, cancelling every trace of the metropolis always dressed in new clothes.

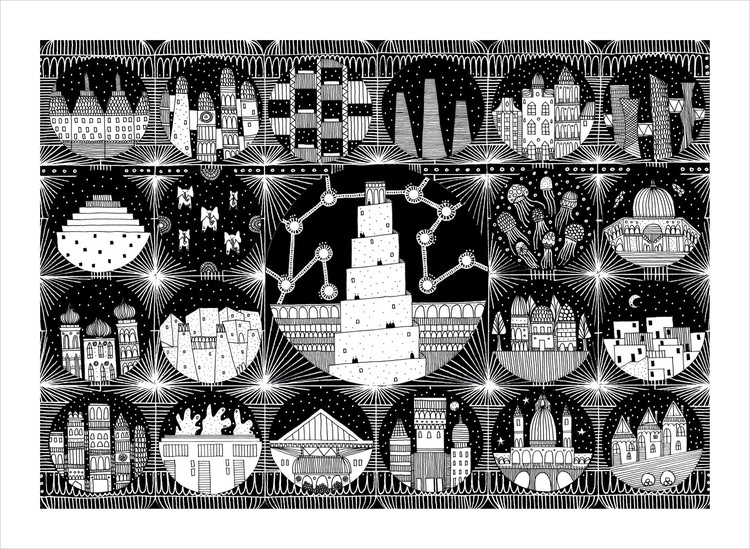

In Calvino’s construction, cities are not made out of things or even people, their material forms represents ideas. Kublai points out to Marco Polo at one point that “You take delight not in a city’s seven or seventy wonders but in the answer it gives to a question of yours.” Marco points out these stories, whether they be true of false, each contain something about the city he actually knows about: “Every time I describe a city I am saying something about Venice”. The cities of this novel remind me of the planets and galaxies throughout Calvino’s Cosmicomics. Each a self-contained world whose characters and rules seem oblivious to the contradictions they would present in neighbouring stories and universes.

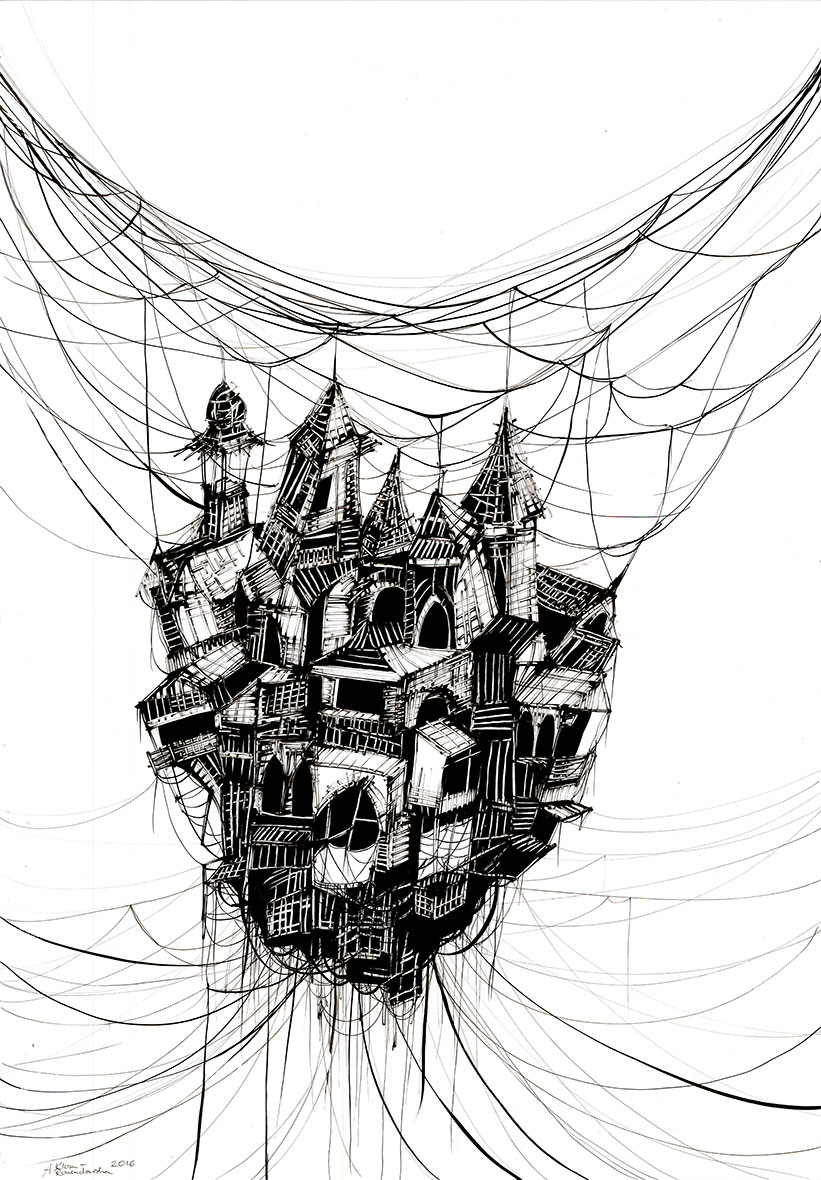

Despite the absurdity of some of the cities, Calvino talks about each in a humane way. An unsurprising disposition for a writer who began his career as an aspiring communist but became disillusioned with it after the brutality of Stalinism and the Soviet Union. There is a tension in the sympathy Calvino gives to each city, a relativistic stance, and that of humanism. Are we to believe that the spider-web city of Octavia presents the best foundation for its citizens?

The city of Octavia

I see the madness in the institutions that develop in these cities as representing the blind design of mother nature and the acceptance of humans have of their lot. There is a feeling that the abstract level at which we learn of the chaos and the sorrow as well as the epiphanies and joys these inhabitants must experience could map onto our own situation; the same one that a distant observer in Andromeda would feel at observing our civilization. Still, with Calvino one can never be sure exactly what he means, and like a dream, these stories may just be projections of our inner thoughts being made with an elusive objective.

Only in Marco Polo’s account was Kublai Khan able to discern, through the walls and towers destined to crumble, the tracery of a pattern so subtle it could escape the termites gnawing.

Invisible Cities is a short book in page count, but a deep book in imagery and poetic content. Calvino’s writing style is luscious and his narratives are always fantastical, creating a world which is both outrageous and gorgeous. Even after reading it, one may feel obliged to open a random page and be pleasantly refreshed at encountering, once again, the city of Argia which is made out of earth where most cities have air, and air where most cities have earth. Special credit must be given to William Weaver for his excellent translation too. Overall this book holds a special place in the Calvino canon.