House Divided (Book Review)

There is a great deal of ruin in a nation.

Adam Smith

Toronto is Canada’s cultural and economic capitol. The city contains 16% of the country’s population, 20% of the its GDP, and 25% of its net job creation. For a young aspiring professional, like myself, moving to Toronto was the obvious career choice. It makes sense that the level of housing prices would be higher in Toronto compared to other Canadian municipalities given the city’s rich amenities and labour market opportunities. But Toronto isn’t just more expensive, it’s growing more expensive. Residential property prices have more than tripled in a 20 year period. As a consequence, the relative price level difference between Toronto and other large cities like Montreal, Ottawa, and Edmonton has grown by 17%, 32%, and 42%, respectively, during this period. How much of this phenomenon is caused by demand compared to constraints in supply? No doubt both are important. The recent publication of House Divided: How the Missing Middle Will Solve Toronto’s Affordability Crisis helps to explain the supply story in Toronto and will be gladly welcomed by the YIMBY movement. The book contains more than two-dozen short essays about Toronto’s dysfunctional housing market, with a specific emphasis on the lack of “missing middle” buildings (e.g. gentle density in the form of duplexes, triplexes, and walk-ups).

[D]uplexes and triplexes, the least intrusive of all multi-unit housing types, are not permitted on two-thirds of the entire land mass of Toronto that is designated for residential dwellings.

The level of Toronto’s residential property prices and composition of its buildings types have been significantly influenced by policy decisions rather than market forces alone. One fact from the book perfectly captures Toronto’s dysfunction residential real estate market: the city has millions of empty bedrooms but a vacancy rate of less than 1%. Most Torontonians have a sense that the city is a boom town in construction. This intuition is erroneous, as fewer housing units were built from 2010-2019 than 2000-09 (on a population-adjusted level). Even though Toronto continues to have the more cranes in its skyline than any other North American city, most of her neighbourhoods have remained static after decades. The cause of Toronto’s strange density distribution is regulation.

(1) The road the ruin

There are many ostensible purposes for why zoning is in the public good. One reason often given is that it makes cities “liveable”. The best neighbourhoods are ones where there is a right mix of residential and commercial buildings, with access to parks and good schools. Toronto’s most sought after neighbourhoods are ones built to a human scale of density: duplexes, triplexes, and walk-ups. Yet most of these buildings were built before 1952 when Toronto introduced its first zoning bylaw.[1] In markets, it is usually the case that when something is in demand, more of it gets supplied. Why then are there so few neighbourhoods with these building types? The answer is simple: it is against city zoning laws to build them.

This problem of regulatory sclerosis is hardly unique to Toronto. Ed Glaeser has shown that, shockingly, average building heights have declined in Manhattan rather than increased over time. In Toronto’s case, the issue is not that apartment buildings are getting shorter, but rather that 1) condos can only be built on a tiny fraction of Toronto’s land zoned residential and, 2) gentle density is prohibited from occurring on the majority of Toronto’s land!

The origin of this dysfunction is the Official Plan (OP). Several seemingly laudable goals underpins its pathology. The first is the goal of “stability”. As John Lorinc points out:

Toronto’s planning policies devote so much rhetorical and regulatory energy to the aspirational virtue of homeowner stability. The latest iteration of the Official Plan makes frequent references to the importance of maintaining ‘physically stable’ communities, and further refinements adopted in 2015 have put meat on the bones of that policy goal by codifying concepts such as the neighbourhood’s ‘prevailing’ character, building heights, lot sizes, and so on.

What does a dysfunctional market look like on the ground for ordinary people? Consider Diaz, who earns \$32K a year and works at the Metro grocery store. She spends 75% of her post-tax income on housing and, though having scraped together \$25K for a downpayment, has been unable to find any bank who would lend her money to buy a house. There is the real estate investor who buys a two-story home in Scarborough and files a minor variance with the Committee of Adjustment to allow an additional suite, which had already been built previously but was otherwise illegal. Despite support from the neighbours, the Committee rules against the addition for this house which is otherwise blocks away from a major road with transit and amenities. Then there is the Dymond family that bought a small bungalow in South Etobicoke and are looking to knock down the building and replace it with a three-storey dwelling so that their in-laws can move in after they downsize. A neighbour complains to the Committee of Adjustment and a mediator forces the Dymond’s to scale back some their plans. The final cost to the Dymond’s of this pointless red tape: \$30K per unit development costs and \$20K for the park improvement levy, amounting to around a quarter of their purchase price.

(2) All roads lead to the Yellowbelt

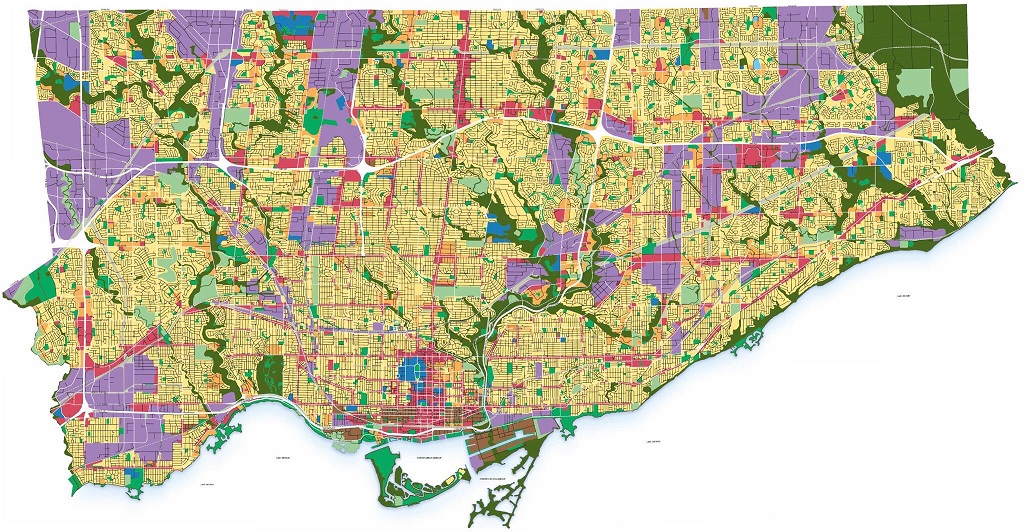

Toronto’s affordability problems have nothing to do with the Greenbelt. Instead, Toronto is constricted from within by the Yellowbelt, a term referring to the area of Toronto’s residential land zoned as “Neighbourhoods” where only low-density houses can be constructed. The term was coined by Gil Meslin due to its striking visual imagery.

You can build anywhere that isn't yellow

The origins of the Yellowbelt go back to the Toronto Planning Board’s 1966 confidential Proposal for a New Plan for Toronto which created three classifications: improvement areas (i.e. for the poor), areas of private development (where high density development could occur), and areas of stability (i.e. for the privileged). It was the first document which stated that “a firm commitment made … that no basic changes through zoning or other public action which is not in keeping with the character of the area will be allowed for a period of ten years.”

While the Yellowbelt may be aesthetically pleasing to look at on a map, it has led to an ossified city with catastrophic consequences for affordability and urban life. One horrifying consequence of the Yellowbelt is that at least half of Toronto’s neighbourhoods became less dense from 2006 to 2016. That’s right: half of Toronto’s neighbourhoods lost population. In this same ten year period, Toronto added almost 250K new residents, while the population loss from her de-densifying neighbourhoods amounted to around 200K. As Alex Bozikovic points out in Why Density Makes Great Places, de-densification is most prominent in the suburban residences. But even areas in the downtown core like Seaton Village saw their populations shrink from 9,200 in 1971 to 5,600 today. As Anna Kramer put it in her essay Inside and Outside:

This population loss in “stable” neighbourhoods works against all the intensification occurring in growth centres.

De-densification is occurring because neighbourhoods which used to comprised of multigenerational households are shrinking. Most of these homes are owned by Boomers whose children have grown up and whose parents have passed away. The Yellowbelt ensures that, as in the case of the Dymond family, attempts to built multi-story homes to attract new occupants will be prevented.

While the demographics of these neighbourhoods have shifted dramatically, their built form has remained frozen in time. Across most of Toronto’s suburban residential areas the city does not permit duplexes, triplexes, laneway houses, townhouses, small apartment buildings, shared houses - in fact, any of the categories of home that reflect Toronto’s shift to smaller families.

Kramer’s essay also made a fascinating point about renovation expenditures. When I was an economist I noticed that renovation expenditure had become a larger share of residential housing investment over time. In the context of supply restriction which prevent housing types from transforming from low to gentle density, this makes sense.

Would allowing denser development help? That is difficult to predict precisely. And yet homeowners are already pouring massive amounts of money into renovating their houses in neighbourhoods. If so much investment is going into essentially rebuilding neighbourhoods within the limitations of existing building envelops and footprints, why not add some more units while we’re at it?

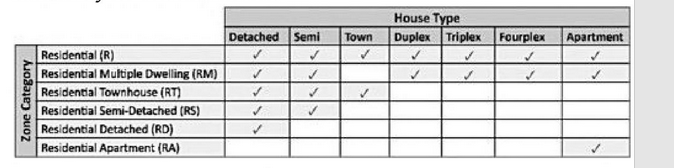

The more you examine the numbers, the worse the picture becomes. The city of North York has a population of 656K but contains only 1,400 bachelor units in its entire housing stock as of 2019. Consider a York University student with limited cash looking for a small apartment. She would be competing for dozens, at best a couple hundred, apartment units the entire city. Half of the 640 square kilometres of land that make up Toronto is zoned residential. But this fact reveals very little as to how much land can actually be developed for condos or duplexes due to the nuances of the zoning categories which are shown in the table below.

A full 200 square kilometres of Toronto’s residential land, two-thirds, is zoned “RD” (or residential detached). Areas like Scarborough, East York, North York, and Etobicoke are all dominated by RD. Yet the other designations can be misleading. For example an area zoned RM may allow for fourplexes, but if there are no existing dense structures, then the “existing character” guidelines in the OP will often prevent even the simplest densification from occurring. The costs of the Yellowbelt is green too. The suburban areas that prevent development from occurring have double the GHG emissions as do the neighbourhoods with pre-WWII building.

(3) History matters

The history of Toronto’s hostility towards development draws from its puritanical and WASPy roots. The city’s medical officer of health, Dr. Charles Hastings, lobbied Toronto Council to pass a bylaw in 1912 to ban apartment’s in residential neighbourhoods and restrict them solely to main streets. As the famous editorial line put it:

It is a short-cut from the apartment house to the divorce court.

The city’s social conservationism even extended to affordable housing projects taken up by the Toronto Housing Company, which city leaders thought “had the taint of charity.” Consider this gem from Toronto Daily Star in 1907 bemoaning that “…in the apartment-hotel [the housewife] has absolutely nothing to do, and we all know who provides mischief for idle hands.”[2] Then there is Alderman A. J. Keeler’s assertion that “…if there is anything destructive of morality and home life it is the herding together of many families under one roof.”[3]

Toronto has a long history of antipathy toward apartments. In the years around 1900, when Toronto prided itself on being ‘A City of Houses’, the arrival of apartments prompted serious pushback from local leaders.

Gil Meslin essay A City of Houses does a good job to connect Toronto’s historical antipathy towards density to modern regulations. The 1912 bylaw banning apartments from residential areas created the political legitimacy that “stability” was a valid public policy goal. The 1966 plan talked about “specific areas of stability” while the 1999 Official Plan talked about “reinforcing and enhancing the established physical character,” and plus ça change, the 2019 OP talks about “development [that]… will respect and reinforce the existing physical character of a neighbourhood”.

The language of “stability” and “character” has been used to exclude walk-up apartments and other forms of neighbouhood-scale multi-residential housing from low-rise residential areas for nearly five decades, illustrating how the 1912 prohibition of walk-up apartments on established residential streets has carried over to the present day.

(4) The political economy

Economic commentators are now beginning to write books showing how Boomers’ have perfected the art of kicking away the ladder (see here or here). After a brief period of rebellion and communal apple orchards, the children of the Greatest Generation reached adulthood and embraced the full-throated capitalism of the Thatcher and Reagan revolutions in the 1980s. Having once accepted the need to pull the state back from the Commanding Heights, Boomers have, unconsciously or not, voted to support anti-market policies that enrich themselves at great expense to society. How have they done this? By tilting the rules of the game to favour returns to existing capital holders compared to labour and new capital formation.

The Canadian state receives half of its revenues from income taxes, with the next largest shares coming from corporate income taxes and sales taxes (15% and 12% respectively). To do this, combined federal and income taxes are at least 30% for full-time workers and can reach 50% for higher income earners. In contrast, only half of capital gains are ever included in income tax filings so the maximum marginal rate is around 25%. And if capital gains occur on your home, then your tax liability is zero. In other words, earnings from actual work need to be taxed at high rates in order to ensure that the trillions of dollars of home equity that has been built up, in part due to government regulations preventing home construction, is seamlessly transfer to the wealthiest generation in human history tax free.

It should be noted that capital gains associated with assets like stocks are usually indicative of true productivity gains to society. For example Tesla may announce that they have developed a new battery system for their electric cars and their stock price will rise in value for their investors. This sort of price increase should be encouraged because it is connected with socially useful innovations. In contrast, increases in residential housing prices are rarely correlated with risky or useful economic activity. True, a well-kept home will fetch more on the market than a poorly kept one, and this is economically useful. But the tripling of Toronto’s property prices is almost solely related to ultra-low interest rates, speculative demand, and constrained supply, rather than a sudden increase in amenities or yard improvement. From the perspective of public finance, taxing a windfall in capital gains from housing makes sense because it does not discourage useful activity (like work or investment).

That is the theory. In practice, the wealthy home owners are politically untouchable. Ed Jackson’s War of the Rosedales is illustrative of the power that rate payers associations have and how they were able to effectively fight against apartments being developed in in their neighbourhood. The last time Rosedale, one of the wealthiest neighbourhoods in Toronto, saw gentle density being developed was in the 1950s.

The situation is so bad in Toronto that I even found myself in sympathy with authors like Ana Teresa Portillo and Mercedes Sharpe Zayas, who in their Urban Legend piece give sociological analysis of what stable neighbourhoods mean.

The notion of ‘cleansing’ a neighbourhood speaks to a white spatial imagination that dreams of a fictional space where stability, stratified wealth, and modern aesthetics coalesce and become understood as a beautification project.

Of course I would never make such a statement myself but I know what they mean! Most of the authors could not be described as market urbanists. But I believe and alliance between the YIMBYs and social justice camps could be formed given the severity of the current situation. I was pleased to see Lorinc cite the fact that supply can have an impact on prices, and gave evidence from Seattle in 2018, which saw prices decline despite the hot labour market and economy due to a massive building boom (see here, here, or here).

(5) Final thoughts

My favourite essay from House Divided was Emma Abramowicz’s story, The Spadina Gardens, about the Hawes brothers’ attempt to build an apartment building at the intersection of Spadina and Lowther in 1905. Though more than 100 years old, the protagonists and their incentives perfectly capture the issues of Toronto of today. The Hawes’, like most developers, were ruthless capitalists. They allowed the local residents to try to buy them out at an inflated price while they surreptitiously bought a lot at the south-east corner of the intersection. The neighbours were the elites of the city and brought significant political pressure against the development. The turn-of-the-century NIMBYs were able to co-opt the city’s City Architect who was sympathetic to their cause. This is hardly surprising given his general concern that overhanging bay windows would encroach into the public realm while worrying that “there is not telling where we will stop if we let this go.” The Hawes’ project was stalled while they waited for building permits to be granted by the City Architect’s office. The Board of Control recommended a stop-work injunction and the city even cut off the property’s water supply. Yet the Hawes’ brother would ultimately be successful after appealing the case to Ontario’s High Court of Justice. One lesson of the Spadina Gardens story is that one method to short-circuit local shenanigans is by appealing to provincial authority.

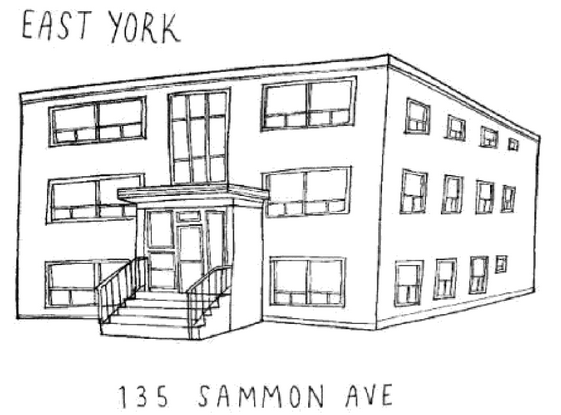

Another chapter I was pleasantly surprised by was Daniel Rotsztain’s The Mid-Rises of Metropolitan Toronto where he includes sketches of mid-rise buildings that are unique for their environment. A triplex on 135 Sammon Avenue is illustrative of how a gentle density can be added to a street of single-family detached homes in a pleasing manner, belying the false premises underpinning the Yellowbelt.

A sketch of gentle density by Daniel Rotsztain

There is a debate amongst economists about whether the rate of productivity growth has hit a period of secular stagnation. New technologies seem to take more resources to develop and provide marginal rather than revolutionary gains to society. Yet one untapped source economic growth and human flourishing isn’t just a piece of low hanging fruit it’s practically dangling in front of our faces but is inedible because of political constraints. House Divided reinforces my view that some of our fetters are of our own making. As the Boomers continue to age, and new political coalitions form, opportunities exist for rethinking local land use planning. Precedents for radical action exist. After WWII a federal wartime order overrode all local zoning restrictions in order to ensure that enough building could occur to house the returning veterans. Consider this modest proposal: all forms of gentle density have the right to be built on every inch of residential land in Toronto. If this is too radical for the City of Toronto, then a higher political authority may need to step in and act in the interest of the public good.