A Concise History of Bulgaria (Book Review)

Before traveling abroad I like to prepare myself for the countries I will be visiting by reading about the place either in history or fiction. In the case of Germany and Austria I found it useful to read some of the classical literature including Kleist, Effi Briest, Mann, and Hesse. Historical overviews of the Austro-Hungarian empire and the history of Germany told through objects were also valuable. While there is no lack of resources for central European destinations, reading materials for a planned trip to Bulgaria were more challenging to procure.1 At the outset my knowledge of Bulgaria was limited to a vague sense of geography (it borders Turkey and Black Sea right?) and the tragic (it picked the side of Germany in both world wars). A quick search through the Toronto Public Library’s archives revealed that when it comes to Bulgarian history, the number of options mirrored the electoral choices during the People’s Republic era: R.J. Crampton’s A Concise History of Bulgaria. Initial Goodreads’ reviews were not inspiring: ‘… drudging at certain points, but quite informative… this book accomplishes exactly what it’s meant to accomplish: provide a concise history of the country’ or ‘… recommended but it’s not exactly a riveting read… just the facts in a straightforward and coherent narrative.’[2] Despite my initial trepidation, I ended being pleasantly surprised by the book. While it is definitely more dry than sweet, Crampton’s writing was informative, balanced, and readable. I came away with what feels like a solid grounding of the country’s most important historical events. I would be curious to see whether the other books in the Concise History series are as good.

The First Bulgarian Kingdom

The ancient state of Bulgaria was one of the last to join Christendom in Europe (beating only the Finns and the Letts in being last to the finish line).[3] Boris I was responsible for imposing Christianity on his subjects and he did so for purely political reasons. A nationwide conversion offered a respite to constant conflict with the Byzantines (a reoccurring theme in Bulgarian history) as well as offering a mechanism to unify the ethnically distinct proto-Bulgars and Slavs. While Bulgaria was one of the last states to join Christianity, its influence on the country’s history would prove to be a profound one well into the modern eta.[4] During the 9th century, it was politics all the way down:

The conversion did not exactly bring entirely satisfactory results for Boris. Bulgaria was made part of the Byzantine church but was denied the right to have its own Bulgarian patriarch or to appoint its own bishops. This strengthened existing fears in Bulgaria that, because in the empire the church was seen as an arm of the state, the church in Bulgaria would become an arm of the Byzantine state and would be used to interfere in the internal affairs of Bulgaria. Fears of potential subversion via the Byzantine church led Boris to ask whether Byzantium’s religious rival, Rome, would offer better terms. Emissaries were dispatched to inquire whether the Pope would allow Boris to nominate the Bulgarian bishops and appoint a Bulgarian patriarch.

This initial tension in Bulgaria’s courtship with the Byzantium-based orthodox church would prove to be another long-lasting feature of Bulgaria’s relationship with its southern neighbour. Not until the modern era would the head of Bulgaria’s church truly be in Bulgaria. Returning to Boris I, he was an eminently practical man in terms of theology and would eventually side with Byzantium over Rome as the latter’s terms were equally strict when it came to appointing Bishops. But at least he asked the right questions.

Boris requested clarification on certain points of doctrine and religious regimen: could, he asked, the Bulgarian tradition of the ruler eating alone with his wife and followers relegated to separate lower tables, continue? On what days was it it permitted to hunt? And could sexual intercourse be allowed on Sundays?

I am reminded of the (possibly apocryphal) story of the Khazar’s adopting Judaism after hearing arguments from all the major religious in regards to which one to convert to. The actual imposition of Christianity on the Bulgarian boyars was a bloody affair even by the standards of the 9th century. More than fifty families of the aristocracy who refused to renounce their pagan practices were to be massacred. The purge of the native elites may be one reason why Bulgaria’s conversion to Christianity was the beginning of the end for its empire. Despite Boris’ pragmatic approach, Bulgarian theological tradition settled somewhere between pure transactionalism and heresy: hermitism (technically bogomilism). This doctrine rejected Church hierarchies and advocated communal living.

Bogomilism has been unfairly criticized for causing all or most of the misfortunes which befell medieval Bulgaria, but bogomilism, in declaring all institutions irredeemably evil, did implicitly condemn any effort to improve those institutions as in the lnog run irrelevant. For this reason bogomilism was essentially negative and did not give rise to any reformist movement or pressures, nor did it stimulate the creative intellectual revolution which the questioning of the Catholic church produced in the west.

Perhaps hermitism can be added to reasons for Eastern European institutional divergence? Constantly caught between the crossfire of warring peoples (the Turks, Serbs, Magyars, Franks, Byzantines, etc), the medieval Bulgarian empire would cease to exist by the end of the 14th century after repeated conquests.

In 1389 the issue was decided when the Serbs were broken in the battle of Kosovo Polje. Bulgaria’s defeat came shortly afterwards. After a three-month siege, Turnovo capitulated in July 1393. The patriarch was shut up in a monastery, the dynasty disposed, the great aristocrats dispossessed and the state dissolved. Resistance continued in Vidin for there more years but it too was eclipsed in 1396. Bulgaria as a state was not to exist for almost half a millennium.

The Ottoman Era

From the start 15th to the turn of the 20th century, Bulgarian history would become inseparable from the rise and fall of the Ottoman empire. While there is still some nostalgia for the historic glories of the medieval Bulgaria empire,[5] the historiography of contemporary Bulgaria is around the subjugation of the Bulgar people by the foreign Turks and their eventual independence after centuries of colonialism. It is interesting to consider whether a country’s independence day is celebrated as a nation becoming itself in the presence of foreign powers (e.g. the United States and Turkey) or from a foreign power (Bulgaria has the Turks, India has the British, etc).[6] While Ottoman rule may have provided some economic benefits to the inhabitants of Bulgaria, it was deleterious to its culture.

Although many Bulgarian guilds flourish under Ottoman rule the conquest had been a cultural as well as political disaster for the Bulgarian nation. Not only did the state disappear and the church fall subject to the domination of Constantinople, Bulgarian language and literature seemed also to die. Bulgarian had once ranked with Greek, Latin and Arabic as the major tongues of the civilised European world, and it had produced a flourishing literature of secular as well as sacred works. But when, in the second half of the 18th century, Catherine the Great compiled her samples of 279 languages and dialects, included in which were some North American Indian tongues, Bulgarian was not even mentioned.

The Ottoman’s subjugation of the Balkan lands has come to be epitomized in the contemporary mind by devshirme: the “child levy” aka the “blood tax”. Like the (putative) droit du seigneur of the medieval Europe, devshirme exemplified the extreme power imbalances between the rulers and ruled. The policy was designed to provide the Sultan with a loyal cadre of soldiers and administrators to help run the empire. The raw material used to fashion these elite bureaucrats were young Christian males from Southeastern Europe, forcibly removed from their villages and trained at elite schools in Istanbul. Those trained in the arts of war were to become Janissaries, while others became senior civil servants. While only a small percentage of the Christan population was affected by this practice, the mere knowledge that Turkish troops could march into your village at any time and demand your first-born would have led to a deranging paranoia for most mothers. The devshirme system did however provide an opportunity for Balkan subjects to be able to rise in the social ranks. For example, one of the greatest Ottoman architects, Mimar Sinan, was “recruited” through devshirme. By the early 18th century the practice had been abolished and attempts to reintroduce it were met by resistance from Ottoman Turks who wanted access to coveted positions. It is interesting the way that one policy can have an out-sized influence on the popular perception of the country (think death penalty in Singapore). It is arguable that the lasting psychic scars of devshirme have continued to foster a fear of “muslims” and “the Turks” in Eastern Europe. This helps to explain why the most popular film in Bulgarian history was, and continues to be, A Time of Violence which portrays an Ottoman cavalry regiment attempting to forcibly convert a Christian village and impose devshirme.

Mimar Sinan's bridge in Edirne

The Ottoman’s influence in central and eastern Europe reached its peak in 1683 when Sultan Mehmet IV’s troops reached the gates of Vienna. After they were defeated, the Austro-Hungarian empire began to conquer back territory and Ottoman vassal states gained more autonomy. By the 19th century, a period known as the kurdjaliistvo had descended with Ottoman administrative capacity having virtually collapsed in the Balkans with lawless gangs and ruthless lords stealing as much from the peasantry as they could.

Bulgaria’s national revival began during this period and is often dated to between 1762, when Paiisi wrote his magnum opus A Slavonic-Bulgarian History of the Peoples, Tars, Saints, and all of their Deeds and of the Bulgarian Way of Life, and 1878, when the country gained independence. It is not clear whether Paiisi had a meaningful impact on the intellectual class during his lifetime; although he was ex post facto celebrated by 19th century historians. Arguably a deeper shift in the psyche of the Bulgarian population was occurring at the time, with Paiisi being an outward manifestation. A growing realization of a unique Christian identity within a Muslim empire that itself had a glorious past would become irresistible:

… of all the Slav peoples the most glorious were the Bulgarians; they were the first who called themselves tsars, the first to have a patriarch, the first to adopt the Christian faith, and it was they who conquered the largest amount of territory. Thus, of all the Slav peoples they were the strongest and the most honored, and the first Slav saints cast their radiance from amongst the Bulgarian people and through the Bulgarian language.

Anyone reading history with a training in economics will notice the way extractive economic policies have tended to be recycled throughout history. During the 18th and 19th century, Bulgaria’s chief export crop was in tobacco and lamb, the former due to its aromatic taste and the latter due to the demand for kosher meat. However, “the profits from animal husbandry greatly outstripped those from arable farming in part because the government exercised a monopoly over the grain trade, buying in the domestic market at low prices and strenuously forbidding exports”. Such a technique has been used by colonial (and post-colonial) governments to tax farmers in West Africa for example. As a rule, the state will always prefer to collect indirect taxes so that there is less accountability and transparency.

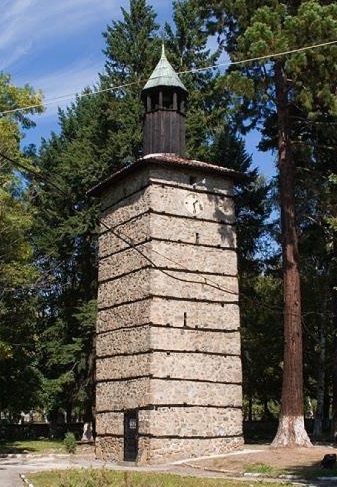

Zlatita clock tower: a symbol of national revival

The 300-year old clock was the first in Bulgaria to have a European architectural style and was a symbol of modernity

Bulgaria’s national revival occurred on many dimensions including language, culture, administrative independence, and, most importantly, religion. Once again the subtle politics surrounding the Bulgarian church would be crucial in determining who controlled the country. When Paiisi wrote A Slavonic-Bulgarian History in Bulgarian, the lingua franca of the educated and merchant class was Greek and the Phanariots dominated most branches of the Ottoman civil administration.[7] Indeed one of Paiisi’s most vehement denunciations was against the Greek bishopric and clerical control of his country’s churches. Battles between Bulgarian dioceses and their Greek clergy began in the 1820s. In the 1830s, a growing number of native Bulgarian priests had been educated in Russia where a pan-Slavic consciousness was encouraged. Despite failing to appoint a Bulgarian to the see of Tarnovo due to the influence of the patriarch in Istanbul in 1835, the Ottomon porte did provide compensation in the form of a Hatt-i-Sherif, which promised equality between Christians and Muslims in the Balkans.

… many Bulgarians chose to interpret it as also promising equality between themselves and the Greeks. In the 1840s the Bulgarians’ protest became quite clearly one not against corrupt Greek bishops because they were corrupt; it was against Greek bishops because they were Greek… the demands produced by the rebels included one for ‘bishops who at least can understand our language’. By the end of that decade there had been protests against Greek bishops in Ruse, Ohrid, Seres, Lovech, Sofia, Samokov, Vidin, Turnovo, Lyaskovets, Svishtov, Vratsa, Tryavna, and Plovdiv.

By the 1860s Bulgarian clerics and bishops had wrested back control of their churches leading to a de facto independence from the patriarch in Istanbul. And in 1870 the Sultan acknowledged the realities on the ground by granting the Bulgarians an officially autonomous (rather than autocephalous) church which would be located in the balat district of Istanbul. The new Bulgarian exarchate faced immediate hostility by the patriarch who would lose millions of his flock (and their corresponding revenue). The Russians, while officially maintaining neutrality, used back-channel methods to prevent a dissolution of the orthodox synod which may have weakened Pan-Slavism. Lastly, the Ottomans were always happier when their Christian subjects were fighting each other than protesting against the Sultan. The Bulgarian church would not become officially autocephalous until 1945 where it was moved to Sofia. The implications for this split along ethnic lines was quite significant.

The Ottoman millet system had made cultural identify a consequence of religious affiliation; the Bulgarians wanted to reverse that order and make religious affiliation a consequence of national allegiance. Such a doctrine, if accepted, would fragment the Orthodox church in the Ottoman empire with Romanians, Vlachs and Albanians, as well as Serbs making similar claims.

The religious struggles were waged largely in ecclesiastical circles but had natural spill-overs into the Bulgarian independence movement. The border lines which governed the Bulgarian exarchate’s spiritual realm would prove an enticing delineation for those pursuing a sovereign state.

In the struggle for the establishment of a separate Bulgarian church the modern Bulgarian nation had been created. The process had begun when, in conformity with the then largely unknown injunction of Paiisi, Bulgarians began to know their own nation and to study in their own tongue. They had since then developed a nation-wide educational system, they had produced their own intelligentsia, and they had pitted themselves against the Greek-dominated clerical hierarchy. The exarchate could now represent the interests of the Bulgarian nation in the Ottoman corridors of power.

St. Stephen's church in Istanbul

Independence

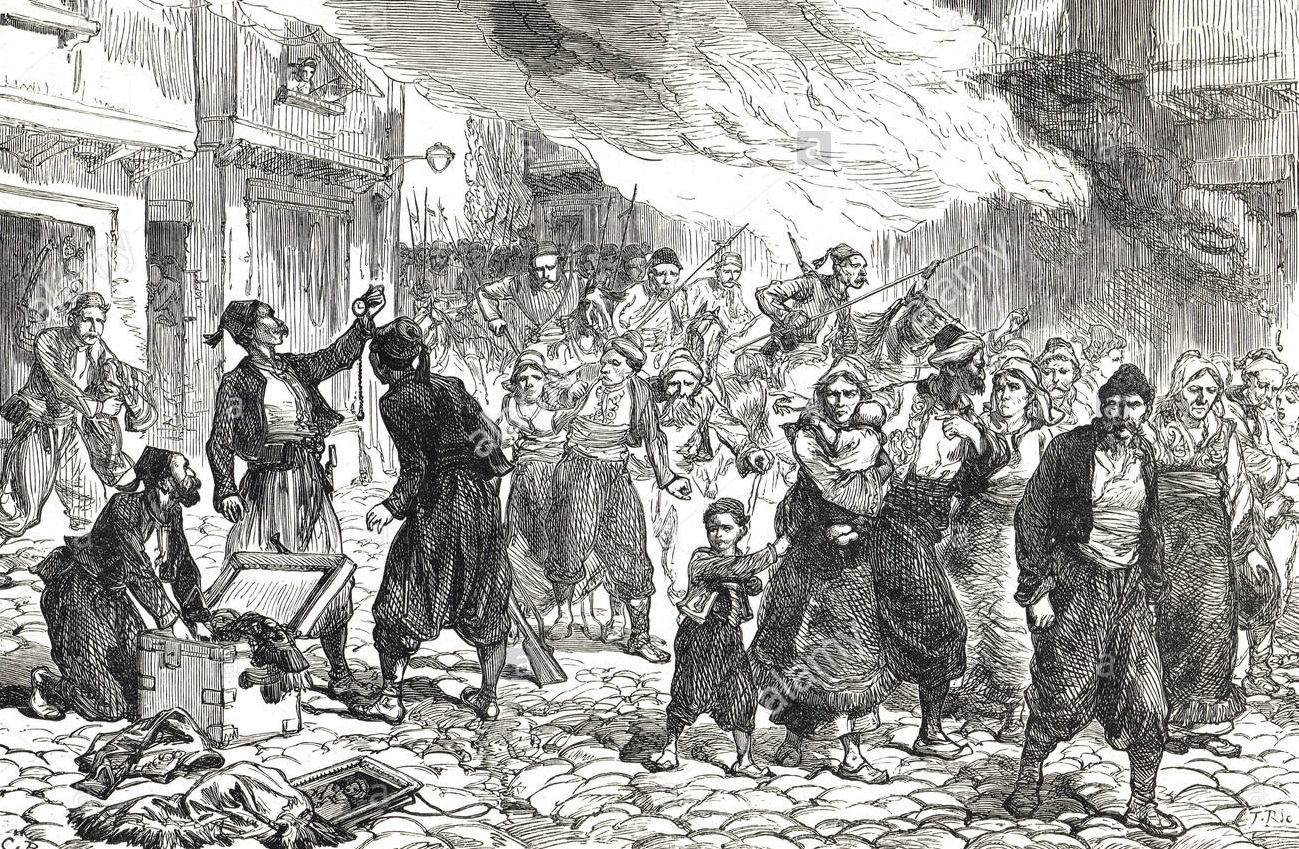

From the Ottoman perspective, the situation in Bulgaria was dire. The spirit of the national “awakening” led to a poorly-planned uprising in April 1876 which was brutally repressed by Ottoman bashibazouks. While failed uprisings and their concomitant Turkish reprisals were hardly new in the Balkans, this time they had become newsworthy. Britain, which had supported the Ottoman empire throughout the 19th century to ensure a balance of power in Europe,[8] had a populace which was growing increasingly skeptical of the need to support “Mohammedans” while they slaughtered “white Christians”. Gladstone was aligned with the popular mood of the time when he demanded that his rival Disraeli (then prime minister) change the stance of British foreign policy to respond to the “Bulgarian horrors”.

In Russia, Britain, and elsewhere there were increasingly loud calls for action to prevent any further outrages. The Bulgarian question had become a European one.

Ottoman reprisals in Batak

The Congress of Europe put significant pressure on the Ottomans to reform their administration of the their European holdings. The Sultan agreed in principle, but he refused to allow foreign supervision to ensure that the rights of Christian subjects were actually being protected on the ground. Russia declared war in response. Despite expectations of any easy victory, Ottoman forces were able to hold onto strong defensive positions for several months with the use of the new breech-loading Martini-Henry rifle. After nearly being driven off by a counter-attack at the Shipka Pass, Russian troops with significant aid from the opalchentsi (Bulgarian volunteers) drove the enemy all the way down to outskirts of Istanbul.

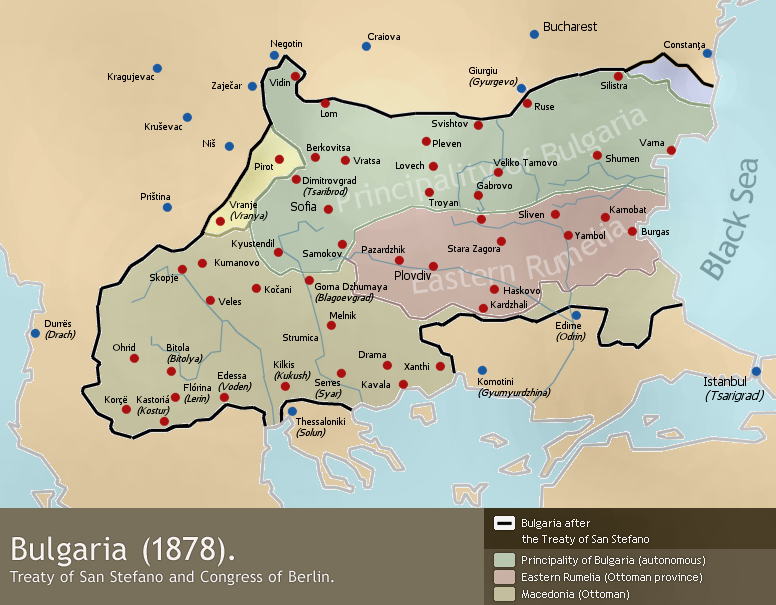

Russia was greeted by the Bulgarian population as liberators. Not only was there a growing sense of Pan-Slavism within the intellectual class, but a fellow Christian neighbour had thrown off the shackles of Muslim rule and all its associated horrors including the devshirme. The initial treaty signed between Russia and the Ottoman’s led the creation of the significantly expansive Bulgarian state which included Macedonia and parts of modern Greece. The British and Austro-Hungarian empire were not happy were such a large Balkan state which was viewed as a client state of Russians. In the subsequent Treaty of Berlin, the country’s borders were reduced to a third of their original size and included a North-South partition which would be infeasible to maintain the long-run.

With the signing of the treaty of Berlin, despite its many shortcomings from the Bulgarian point of view, the modern Bulgarian state had been born. Unlike the Bulgarian church it was the creation more of external than internal forces.

Bulgaria's borders after revision

The one place in the book where the prose become especially engaging is during the post-independence period. This turns out to unsurprising as Crompton’s academic work includes Bulgaria 1878-1918: A History. Leading up to the First World War, Bulgarian historical development is focused around the solidification of the nation state, an establishment of the monarchy, and its relations with its Balkan neighbors and the regional great powers. Less than ten years after its independence, Bulgaria would be attacked by the newly-formed and revanchist nation of Serbia and would end up winning its most glorious (and arguably last) military victory in Europe.

The battle of Slivnitsa was a remarkable achievement for an untested army shorn of its senior officers. It was equally an achievement of the nation as a whole, and it is worth recalling that the highest incidence of medals for gallantry was amongst Muslim troops. More than any other event the battle of Slivnitsa welded the Bulgarians north and south of the Balkan mountains into one nation.

Bulgaria’s new government had inherited several foreign-owned railways and faced costly decisions about whether to expand capacity. Inevitably this led to large debts being accrued to pay significant sums of money to foreign shareholders. While Bulgaria’s government was elected democratically, it displayed a level of ruthlessness to internal dissension that appeared to be necessary for a fledging state. Most importantly, domestic stability was seen as a necessary requirement for a country in search of a hereditary monarchy. That Bulgarian thought it needed a foreign nobleman to ensure legitimacy comes across as quaint today, but it was seen as essential at the time. Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was eventually courted to the position. His rule would start in 1887 and last to the end of the first world war. Ferdinand’s main baggage was his Catholicism, which was the main obstacle preventing a closer relationship between Bulgaria and Russia. Crompton elegantly explains the historical considerations of the time.

This faced the Bulgarian regime with a difficult choice. Conversion [of Fredinand] would be immensely popular amongst the Bulgarian people as a whole, as would reconciliation with the Russians who had liberated them: how could a Bulgarian government refuse a price which the people were eager to pay for an item which they all wanted to purchase? And, it was pointed out the king of Romania had recently agreed to the conversion of his son. The difference was that the king of Romania was a Protestant. He did not have the pope to answer to, nor did he have staunchly Catholic families, his own and his wife’s, to contend with. Ferdinand’s was not a conscience frequently troubled but in this case he felt a genuine dilemma, pulled in one direction by his feeling for his mother and his wife and, no doubt, his own immortal soul, and in the other by the obvious political advantages to be gained from accepting Russia’s terms. He decided in favor of the latter. He knew that recognition and reconciliation with Russia would bring greater internal cohesion. He knew too that with the situation in the Ottoman empire deteriorating the Macedonian question was bound to become more acute, and should it become critical and his freedom of action be restricted because he had not mended his fences with Russia, he would have failed his adopted nation and would personally be in grave danger of deposition of worse. On 3 February 1896 it was announced that Prince Boris would receive an Orthodox baptism. Tsar Nicholas II, though he would not attend in person, would stand as godfather. Two weeks later … the sultan, with Russian backing, recognized Ferdinand as prince of Bulgaria and governor of the Eastern Rumelia. Within a few days all the great powers, Russia included, had done likewise.

The state played a significant role in the direction of Bulgaria’s early economic development. While the private sector held the means of production, the government encouraged specific “strategic” sectors that were capital intensive including mining and metallurgy. As with the railways, the financing of these endeavors would require significant amount of borrowing from foreign creditors. Ironically every single policy that Bulgaria pursued at the time would now be in violation of some international economic agreement from state aid to non-discrimination.[9]

State encouragement was to take the form of free grants of land for factory building together with financial help for the construction of any necessary road or rail links, preferential rates on the state railways for finished products, free use of state or local authority quarries and water power, tax advantages, preference in the awarding of state contracts even if the native products were more expensive than imported ones, and a monopoly in supplying certain items within specified geographic limits.

Bulgaria’s decision to enter WWI a year after the war began on the side of the Central Powers would prove to be a fateful one. Fleeting territorial gains in Greece, Macedonia, and Serbia would be paid for at Versailles, and Ferdinand would abdicate at the end of the war. Compared to the Germans the Bulgarians received a lighter punishment, with only a sliver of their territory being given to the Romanians. The immediate political beneficiaries of the post-war situation were the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union (BANU) party which ran the country from 1920-1923. While there are still some modern agrarian parties in existence today in Europe, it is difficult to imagine a country being run in the interests of small landholders and peasants. Such policies managed (somewhat impressively) to be antagonistic to the urban middle-classes, capitalists, and communists! The combination of compulsory labor service and secondary school, progressive income taxes, and support for the League of Nations makes BANU and their quixotic leader Aleksandar Stamboliyski difficult to pin down on the political compass but interesting nonetheless!

… part of BANU’s offensive [was] against those whom it considered parasites. Lawyers were … in the firing line. They were denied the right to sit in parliament or on local councils, and were barred from major public office. The agrarians also established new lower courts to deal with issues such as boundary disputes, and in these courts peasants were to plead their own cases before judges elected by the local populace. The agrarians also greatly limited the king’s power to make appointments, and they required banks to help fund credit cooperatives. BANUs main objective, however, was to redistribute land.

Stamboliyski would be deposed in a coup and Bulgaria’s interwar years would continue to be plagued with volatility. The country even had a brief fascist period (before another coup deposed that government) which would see society divided “not by occupational category but … copying the Italian fascists, had divided society into seven estates: workers, peasants, craftsmen, merchants, intelligentsia, civil servants, and members of the free professions”.

Boris III shared his father’s misfortune in having to pick whether to side with the Germans in a world war, and error in concluding they were likely to be the winners. As with the first world war, Bulgaria was a late joiner (18 months after Hitler’s invasion of Poland), and would only dedicate forces for nearby territorial acquisition. Despite being at war with Russia twice in a row, the Bulgarian population maintained a strong affection for their former liberators and fellow Slavs. Boris’ policy to prevent foreign deployments was also based on the fear that a victorious general returning from the front may depose him with the backing of the Germans who found the Bulgarians to be unreliable allies, especially in their failure to hand over their Jewish population for extermination.

[Boris] refused to allow the recruitment even of a volunteer legion for duty on the eastern front and when the Germans asked for permission to use fifteen Bulgarian pilots trained in Germany Boris agreed only on condition that they served in North Africa, and even this permission was soon revoked.

The Communist and Modern Era

The Red Army’s arrival in Bulgaria in 1944 would not be greeted with the same celebration that occurred in 1878. However the Bulgarian Worker’s Party (which would become the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP)) was no doubt glad that the Allied Control Commission (basically the Russians) had ensured their party a leading role in the country’s new government. The Soviets used the standard playbook of making sure the communist party held the important cabinet roles (the police, the courts, the internal security apparatus, etc) in the post-war coalition government so that if (or when) elections failed to achieve a communist state, the only people with guns would be under their control.

The government controlled the radio and the distribution of newsprint, whilst the ACC, in effect the Soviets, had the right to sanction the import of foreign films and printed material; thus the FF [the government] had a virtual stranglehold over the media, but should a fail-safe be needed opposition newspapers could always be muzzled by the communist-dominated unions in the printing and distributing sectors… For the communists, the problem was that the local intelligentsia and political establishment had not been decimated by the Gestapo or its local equivalent, and therefore the potential pool of opposition was greater than in other states; the Bulgarian intelligentsia and political classes were paying now for their relative ease in the war.

The biggest headache for implementing a Red takeover were not just the abundant number of untainted elites (see above) but the fact that the rural peasantry made up more than 80% of the country.

The communists were in a difficult position. They could not, as they had done in Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and eastern Germany, win over the peasants by offering them confiscated aristocratic or émigré land; there were no aristocrats or émigrés and the vast majority of peasants had enough land anyway. All the communists could do was launch a front assault on agrarian institutions and personalities.

By 1947 the communists had grown weary of political opposition and began to arrest their opponents. By 1949 most civil institutions had either been destroyed or converted into Marxist-approved ersatz versions of their former selves. Unlike some of its Eastern European neighbours, Bulgaria would have no internal uprisings of the type seen in Budapest or Prague. Indeed Bulgaria tracked both a period of Stalinization and De-Stalinization under Todor Zhivkov who would run the communist party from 1954 to its collapse in 1989.

[Bulgaria’s] main feature remained an almost total obedience to the Soviet Union, especially in foreign policy; in September 1973 Zhivkov remarked that Bulgaria and the Soviet Union would ‘act as a single body, breathing with the same lungs and nourished by the same bloodstream’. On issues such as the Vietnam war, the third world, the Middle East, and Latin America there was not a hair’s breadth of difference between Sofia and Moscow. So far did Zhivkov’s devotion to the Soviet Union go that we now know that on two occasions he proposed that Bulgaria should be incorporated in the USSR. Krushev turned him down because he thought Zhivkov saw in such a union easy access to higher living standards; Brezhnev rejected the offer because he knew it to be impracticable in diplomatic terms.

Perhaps the reasons why Bulgaria avoided internal strife during its communist era helped to explain why it had one of the smoothest transitions out of totalitarian rule. In 1989 with neighboring Romania plunging into mayhem and the Berlin wall being dismantled, the BCP ousted Zhivkov and wisely agreed to go into coalition with now-legalized opposition parties which had coalesced into the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF). Elections were held a year later and the reincarnated Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) managed to win a slender majority; a testament to how rebranding and seeing the writing the on the wall is always a good strategy for maintaining power. However the UDF would win the subsequent election and Zhivkov would be successfully prosecuted and sentenced to seven years in prison. A relatively light sentence for a man who had robbed and crushed the flourishing of his country for almost half a century. His lenient treatment was a sign of Bulgaria’s relative political maturity. Many other former communists were punished through the loss of jobs or lands in a period of lustration.

Zhivkov was the first of Eastern Europe’s former leaders to be tried and convicted but he was to be allowed to serve his time under house arrest rather than in jail.

Like all other former Warsaw Pact countries, Bulgaria’s economic transition from state planning to free markets was a difficult one. In 1997 Bulgaria adopted the harsh economic policy of pegging the leva to the Deutche Mark in an attempt to control spiraling inflation. A country which adopts a currency peg loses the ability to set domestic interest rates and control its money supply effectively tying itself to the mast of a foreign economy. Because German monetary policy is conservative the growth of the money supply in Bulgaria to effectively flat-lined. Unsurprisingly inflation fell from 243% to 1.7% within two years.[10] By showing it could swallow some bitter medicine Bulgaria had ingratiated itself with its European allies and would begin its road to EU accession.

By 2001 the Kostov’s administration was considered a model student by the EU, NATO, and the IMF, but it was having a harder time with the electorate due to a series of corruption scandals. In what amounts to the most fascinating political reversals of fortunes in dynastic history, the former deposed King of Bulgaria Simeon Borisov von Saxe-Coburg-Gotha had returned to Bulgaria in 1996 and by 2001 had established a party that would win a decisive victory in the country’s election that year. Just as in 1878 when the nation of Bulgarian felt it needed a hereditary monarchy to ensure itself international credibility, more than 120 years later Bulgarians felt that the regal touch would help their country build connections to the outside world and help to remove the associations of graft and gangsterism.

Unlike all previous leaders in post-totalitarian Bulgaria, [Simeon] had never been part of the pre-1989 system, and had no associations with either of the two main groups which had dominated political affairs since the fall of Zhivkov. But his greatest electoral asset was that he was absolutely free from any suspicion of personal corruption.

Simeon’s policy built on the Kostov regime and continued to push for admission to the EU and membership of NATO (which would happen in 2002). A fascinating interview with Charlie Rose from the time suggests a man who is worldly, thoughtful, and reticent. A year after Borisov left office Bulgaria was accepted into the EU. The accession was built on many politically ‘courageous’ decisions that took place under the former King’s rule. Reforms to energy markets, mothballing nuclear reactors, and selling off former state-owned industries were particularly challenging. Naturally these economy drives tended to have disproportionate and negative effects on the low-skilled part of the labour force, many of whom had voted for Simeon’s party.

Return of a King

By taking a step back Bulgaria’s history can be seen as one of amazing swings and cycles.

In the political arena decisions on whether to align with Russia or its adversaries could and did prove critical. In 1913 and 1915 and again in 1941 Bulgaria chose to defy Russian interests with ultimately catastrophic consequences for Bulgarian aspirations towards full national unification. After 1944 Bulgaria’s rulers opted for close relations with Russia at enormous cost to the political liberty of the Bulgarian citizen, as well as to the long-term economic and environmental well-being of the country. In the immediate aftermath of the changes in 1989, Bulgarian foreign policy swung around full circle. Close associations with the EU became the ultimate goal of Bulgaria’s foreign policy-makers and there was a wave of intense pro-American feeling. Bulgaria was reintegrated into the western world during the Afghan and Iraqi wars and the politicians of Sofia showed considerable skill in ensuring that their commitment to helping the US-led wars did not seriously or lastingly impair their standing in the EU… The economic revival of Bulgarian communities in the 19th century was based mainly on the expansion of trading relations not with central and western Europe but with the rest of the Ottoman empire, that is with European Turkey and Anatolia. Liberation in 1878 meant exposure to what the Bulgarians of the day would have called ‘European’ competition, bringing widespread economic dislocation and the destruction of much of the existing manufacturing system: and here is another obvious parallel with the post-1989 situation.

Many of the great and tragic decisions by Bulgarian leaders has been in regards to irredentist policies towards Macedonia. Bulgaria’s numerous defeats during the second Balkan war were caused by a vain attempt to prevent Serbia and Greece from annexing Macedonia. The prospect of winning back these lost territories was what convinced King Ferdinand to back the Germans in the first world war. And in 1941 “when King Boris came to the conclusion that Bulgaria could no longer be neutral he sweetened the bitter pill by swallowing most of Macedonia”. However it is a promising political development that the issue of ‘greater Bulgaria’ has largely disappeared from contemporary Bulgarian politics.

Bulgaria’s main challenges today come from a stagnating economy driven by poor demography. A combination of low fertility rates and outward migration to other EU states has led to a shrinking population. Shockingly Bulgaria’s population is 2 million fewer today than it was in 1989. A long-standing cultural critique of the country has been that its legacy of bogomilism and monastic introspection has caused its people to be relatively apathetic to politics. For example during the crucial negotiations that took place during the Treaty of Berlin, Bulgaria did not have a single representative in the German capitol and instead relied on the Russians to advocate on their behalf. The future of Bulgaria may be a positive one if its parties and politicians deliver public policies that are in accordance with the economic trends of the 21st century. If there is instead a retreat to a shabby nationalism that has taken hold in the likes of Hungary or a Putinesque cronyism based on oligarchic entrenchment, then the future may be bleak.

The dichotomy between an eastern and a western orientation has been an inevitable consequence of Bulgaria’s geographic position and her historical development. These two factors have dictated that Bulgaria, occupying a nodal position between Europe and Asia will always be on the edge of both the east and the west.

-

Coronovirus obviously put paid to these plans. ↩

-

Three of five stars is still better than most people would rate the Bulgarian Communist Party. ↩

-

The Letts evoke no strong emotion in me other than their being referred to in Cole Porter’s classic line: In Spain the best upper sets do it; Lithuanians and Letts do it; Let’s do it, let’s fall in love”. ↩

-

For example the Bulgaria Orthodox Church would play an important role in protecting the country’s Jews from deportation to Nazi death camps, making it the only Axis or invaded power to do so. ↩

-

The image of Krum the fearsome, Khan of Bulgaria drinking his wine from the skull of the (former) Byzantine emperor Nikephoros I suggests the height of Bulgarian martial prowess. ↩

-

Of course the United States broke free from British rule, but contemporary emphasis has very little to do with British Colonialism per se and more with the establishment of uniquely American institutions: a constitution and a federalist republic. Turkey was also occupied when Ataturk managed to evict foreign forces, but again Turkish independence has very little to do with foreign Italian troops and is instead celebrated with the creation of a secular republic and ethnic Turkish state. Furthermore, the legacy of British rule in the United States, or Western occupation after WWI are not used in the US or Turkey for arguments about current political challenges. In contrast, contemporary arguments are made about the economic and political dysfunction in modern Bulgaria and India with respect to their colonizer: …after 500 years of being under the Ottoman yoke… or …how Britain stole $45 trillion from India…. ↩

-

Most economic guilds in the Balkans conducted commerce and kept their records in Greek. Emblematic of the growing linguistic tension was when the aba (a type of rough wool) guild in Plovdiv, Bulgaria’s long-historic capitol before Sofia, split into separate Greek and Bulgarian sections. ↩

-

Britain’s primary reason for joining the Crimean War in 1853 in alliance with France was to prevent Russia from absorbing most of the Balkans and possibly taking Constantinople. ↩

-

A fact that Ha-Joon Chang would likely enjoy pointing out! ↩

-

Milton Friedman once famously said that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. ↩