Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance (Book Review)

Why didn’t our neighbour leave that abusive man? Why did she spend her money on drugs? Why couldn’t she see that her behavior was destroying her daughter? Why were all of these things happening not just to our neighbour but to my mom? It would be years before I learned that no single book, or expert, or field could fully explain the problem of hillbillies in America. Our elegy is a sociological one, yes, but it is also about psychology and community and culture and faith.

I still remember calling my mother late in evening on November 8th, 2016 telling her that Trump was poised to take the electoral college as it became increasing clear that Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania were careening towards a Republican majority. That I registered this news with some slight relish stemmed from the feeling that I was relaying history in the making as well as that troubling aspect of human nature that savours getting to bear the tidings of bad political news. It is worth reflecting on how unanticipated the results were relative to popular media’s expectation at the time. Consider this headline from The Washington Post on October 24th:

Donald Trump’s chances of winning are approaching zero

Or from The Independent on November 5th:

Survey finds Hillary Clinton has ‘more than 99% chance’ of winning election over Donald Trump

More reasonable forecasts from Nate Silver’s 538 blog gave Clinton a 71.4% chance and the NYT’s Upshot blog gave her an 85% chance of victory. As many of the “lean Democratic” states were coming in red, a disheveled Nate Silver would appear on CNN and warn that the existing predictions are meaningless because the swings across States were likely to be correlated: if Clinton’s vote share was lower-than-expected in Michigan it was also likely to disappoint in Ohio, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, etc, because these states had a similar demographic profile. In other words, the white working class voters who voted for Obama once, or even twice, were not showing up for HRC. The Rust Belt refers to a geographic area mainly along the Great Lakes that contains the aforementioned states (along with some others) that have seen a precipitous decline in economic activity since the 1960s. This region once contained some of the wealthiest and most progressive (not necessarily politically) cities in the United States such as Detroit and Pittsburgh. Cities where African Americans moved to escape poverty and the Ku Klux Klan starting at the turn of the century and where many economically poor whites from the Appalachian region moved to after the end of the Second World War.

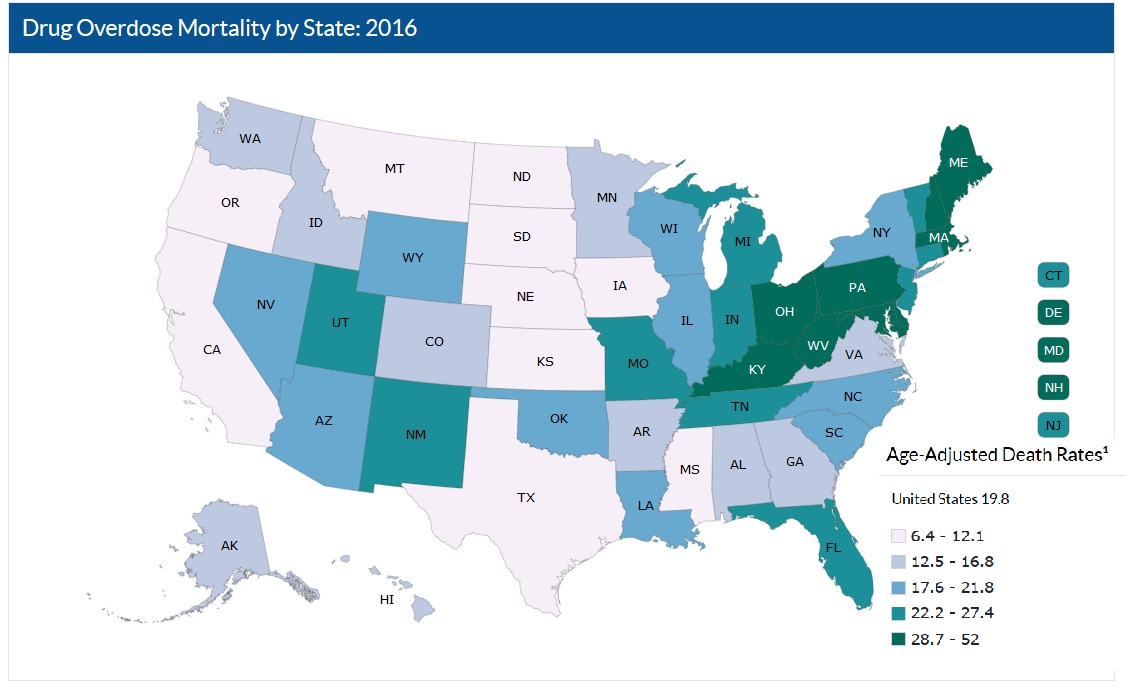

These places that once offered career opportunities and communities that matched the aspirations of families seeking the American Dream have evaporated and have been replaced by strip malls, unemployment, and some of the highest rates of opioid overdoses in the country. Research has shown a correlation between Trump’s vote share and the chronic use of prescription opioid drugs. Other research by Case and Deaton has shown that middle-aged non-Hispanic whites in the U.S. with a high school diploma or less have experienced increasing midlife mortality since the late 1990s… The combined effect means that mortality rates of whites with no more than a high school degree, which were around 30 percent lower than mortality rates of blacks in 1999, grew to be 30 percent higher than blacks by 2015. Declining life expectancy is totally unheard of in any Western country in the post-era for almost any demographic group.

Figure: Drug overdoses are concentrated in the Rust Belt

Source: CDC

The timing of J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy was a publishers dream coinciding in the same year that Trump’s electoral victory stunned many of the liberal pundits. In this beautifully written book Vance gives us a vignette into his family’s troubled past and present history–a story of a briefly held spell of American prosperity followed by a tragic decline. Vance’s grandparents (affectionately referred to as Mamaw and Papaw) left Kentucky in hurry in the early 1950s due to a teenage pregnancy (that ultimately resulted in a miscarriage). The couple ended up in Middletown, Ohio, where Papaw found a good paying job with Armco Steel. While the family income of Vance’s grandparents was at a level unimaginable to their Kentucky relatives, they found their cultural heritage was ill-at-ease (to put it mildly) with the traditional white suburban culture of Ohio. The Scots-Irish hillbillies of the Appalachians, to which Mamaw and Papaw definitely belonged, more closely resembled the violent and irascible behaviors of the 17th century highlanders than the ideal American family à la I Love Lucy.

Behaviors such as blood feuds, extreme domestic violence, and unadulterated profanity as well as a strong honour culture shocked the local Ohioans who resented having 20th century Hatfield and McCoys in their midst. To give a memorable example, in retaliation for Vance’s father being scolded by a store clerk for playing with the toys, Papaw decided to trash the store. After the episode the family continued to peacefully shop as though this behavior were normal and constituted an uneventful day. In another case of shocking casual violence, Mamaw doused Papaw in gasoline and set him on fire for failing to keep sober and was lucky to only suffer minor burns due to a quick response from his children. While Vance’s grandparents clearly had their share of social ills including alcoholism and matrimonial disputes they remained thrifty and hardworking throughout their lives. Their children did not fare so well. Vance’s mother went through four marriages before J. D. had finished high school, went to rehab several times, and repeatedly lost her job as a nurse. His father was mostly absent throughout his life.

We learn that the hillbilly culture is one that is full of contradictions. An especially pernicious type of double think is seen in their attitude towards work. While there is no lack of complaining about moochers and welfare queens, his brethren have perfected the art of living on the dole for themselves. Anecdotes of friends who railed against the Obama economy but also left their jobs in order to avoid having to wake up too early are given. Part of the honour culture means never admitting to weakness. Studies or media reports which report socioeconomic ills in white working class neighbourhoods are seen as personal attacks. By casting the problems of white working class in terms of exogenous forces (Chinese trade practices, Islamic terrorism, Obama’s preference for non-Whites, illegal immigration, etc) rather than endogenous cultural problems, Trump’s political entrepreneurship paid huge dividends. Trump was the first politician in decades to whom poor whites felt attached to because he didn’t seem to despise them (or possibly the attachment stemmed from a transitive assumption that since the people who despised Trump also despised them he must onto something).

As a culture, we had no heroes. Certainly not any politician–Barack Obama was then the most admired man in America (and likely still is), but even when the country was enraptured by his rise, most Middletonians viewed him suspiciously. George W. Bush had few fans in 2008. Many loved Bill Clinton, but many more saw him as the symbol of American moral decay, and Ronald Reagan was long dead. We loved the military but had no George S. Patton figure in the modern army. I doubt my neighbors could even name a high-ranking military officer. The space program, long a source of pride, had gone the way of the dodo, and with it the celebrity astronauts. Nothing united us with the core fabric of American society. We felt trapped in two seemingly unwinnable wars, in which a disproportionate share of the fighters came from our neighborhood, and in an economy that failed to deliver the most basic promise of the American Dream–a steady wage.

At the beginning of the book Vance notes that there is nothing particularly special about his life. His greatest accomplishment (before writing this book anyways) was to graduate from Yale Law School. But this is an accomplishment shared by around hundreds of living alumni. What makes this book special is that it describes the journey of someone who statistically almost never makes it to an Ivy League university. Vance acknowledges that his success in life is owed to many lucky breaks and that his biography is not much different from the young men he grew up with who are now high school dropouts. Even his sister who has ended up with a stable and loving family missed the opportunity for a college education because she became pregnant as a teenager. Despite an absent father and an addict mother, Vance had his grandparents. While they were highly flawed individuals, they did everything they could to help him to get into college and provide a (relatively) stable home life. After graduating from college Vance spent four years in the Marine Corp. This stint taught him life skills including personal finance, diet and exercise, hard work, and self-respect: i.e. the personality traits that are required to have a successful middle-class life and career.

In addition to the financial resources and stable home lives that middle-class families provide to their children, there are also subtle cultural skills that are often unwritten but essential for advancing in American society. These include manners of speech, cultural references, how to dress to interviews, what sort of questions to ask, and what goals to aspire to. Most kids from Middletown Ohio would not know that in-state college may be more expensive than private schooling after bursaries, or that finance is a career, or that becoming a doctor or a lawyer requires studying specific subjects in advance.

Vance doesn’t think that public policy will be able to do much to solve the economic plight of poor whites in the Rust Bust and Appalachian states because their challenges are mainly cultural. That is not to say that there are no policy prescriptions that could make an impact on the margin. Rather, since only cultural forces can explain why these disadvantaged whites have faired so poorly in contemporary American society where many other social groups have faced the same external pressures but done much better, it seems reasonable to assume that only countervailing cultural forces can undue them. This book is essential reading to understand when culture trumps economics (pun not intended) and how populist political posturing will likely continue to hold purchase in the United States.