Empty Planet by Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson (Book Review)

I have always been skeptical of proclamations concerning natural the world’s inevitable resource depletion. The loss of Paul Erlich’s $10K to Julian Simon in their famous wager has stayed with me. Most people think of resources in an engineering sense: if a car has an X gallon tank it will run out of fuel in Y hours if you drive it at Z-km/hr. Or on a planetary scale: if humanity drives X cars with Y fuel efficiency, we will run out of oil within Z years. While this type of thinking makes sense for closed mechanical systems, like a car engine, it is an inappropriate framework for thinking about scarcity in economic systems. The use of prices in a market economy ensures that the cost of natural resources will scale to their relative scarcity.[1] In an internal combustion engine, there are no internal prices and the car will use the same amount of gasoline whether the tank is full or nearly empty. But in economic systems, prices will continue to increase as the availability of a resource goes down. So there will always be gasoline available for sale, the question is at what price.

A simple retort to the point that prices ensure some availability of a resource is that in practice this is highly problematic. If our standard of living collapses because oil costs $300 a barrel, who cares if some rich motorhead can afford to drive his Maserati on the weekend while the majority of humanity starves. But this misses another important point about resources in an economic rather than an engineering paradigm: that the value of a given product is relative to all other products and the state of technology. It is true that there must be some finite amount of oil in a molecular sense on planet earth currently. However suppose a new engine technology is developed so that the fuel efficiency of all motor vehicles were to double. Has the physical amount of oil reserves increased? No–not at the atomic level. Has the effective amount of oil doubled? In the sense that we care about it–yes. Herein lies the point: the amount of resources for an economic system is ultimately determined by human ingenuity and not by the quantity of atoms.

While human population growth may not deleteriously effect the level of available resources for the reasons discussed above, it will surely increase the level of pollution. While per capita carbon emissions are a fair metric for basing treaties on, the ozone does not care about relative carbon output, and the aggregate number is what will ultimately determine whether the worst effects climate change can be stymied. The development of carbon-reducing technologies and the number of carbon-producing humans (and livestock) matters for the future of planetary health. The UN population division in their most recent report projects that the world population will grow from 7.7 billion today to a peak of 10.9 billion by 2100. In Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson’s new book Empty Planet the two Canadians take issue with the UN population predictions and suggest that humanity’s population will more likely peak at 8.5-9.5 billion and decline rapidly thereafter. In the report cited above, this approximately corresponds to the UN’s “momentum scenario” in which fertility rates (the average number of children a women will have in her lifetime) falls to 2.1 (the replacement rate) for high-fertility countries and population peaks at around 9.2 billion in 2060 and holds steady.

Bricker and Ibbitson acknowledge that the UN’s population predictions have been spot on up-to-now. For example the agency’s prediction in 1980s as to when the earth would hit 7 billion humans was remarkably accurate. Unlike other prediction problems, demography is largely destiny. Errors in global population predictions can arise from unexpected changes in either the input flow (i.e. fertility rates) or the output flow (i.e. life expectancy). Empty Planet focuses on errors on the input side: how many humans are born each year. The Population Division uses a simple backward-looking method to determine a country’s fertility rate change over time: the fertility trajectory of country A will look like the fertility trajectory of country B, when country B had the same fertility of country A (but now has a lower fertility). The variation around this trajectory is embodied in the UN’s high, medium, and low-variant fertility projection. Bricker and Ibbitson suggest that the medium (expected) trajectory is too high optimistic and that the low variant is more likely to materialize.

Where exactly does the disagreement between the book and the UN predictions come from? There are two areas of contention: first whether countries that have reached or dipped below the replacement rate will hold steady and second whether countries with fast-growing populations will gently decline towards the replacement rate. I think it would come as a surprise to most people that the fertility rates in countries like Brazil (1.8), Mexico (2.3), Malaysia (2.1), Bangladesh (2.1), Iran (2.0), India (2.3) and Thailand (1.5) are all near the replacement rate (and all are falling). These countries are now contributing to future population growth through the aging of their societies rather than through more babies (i.e. the inflow remains the same or smaller but the outflow is falling even faster for now). While Bangladesh and Iran have had surprising successful family-planning campaigns,[2] how can fertility rates be low in the favelas of Brazil or the slums of Calcutta? In these countries women are having birth control done through sterilization since this is often provided for free by the government. In Brazil this practice is known as fábrica está fechada or shutting down the factory. Women will pay a little extra to have tubal ligation done when performing a cesarean section during childbirth. In countries where sterilization is common, baby booms from positive economic growth are now close-to-impossible.

As K.S. James tells us, it’s typical for an Indian woman to be sterilized immediately after he second child, at around twenty-five years of age.

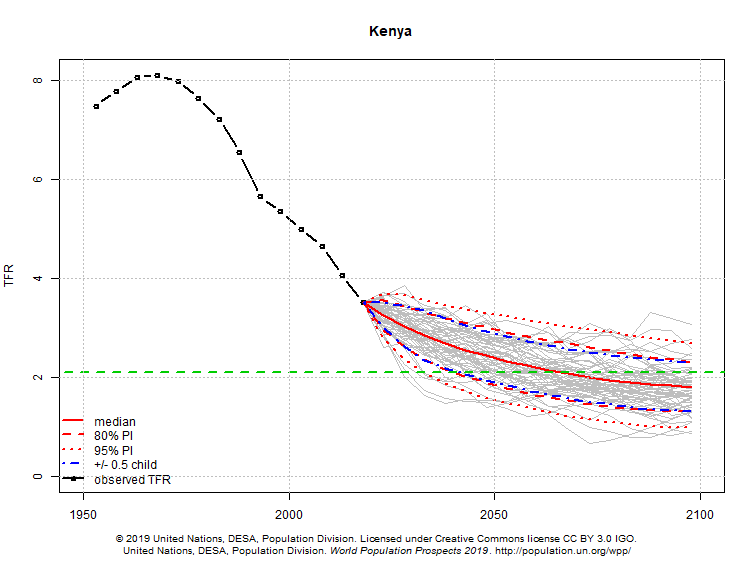

As Jorgon Randers points out “… in an urban slum it does not make sense to have a large family.” The fertility drop-off in these middle-income countries is without precedent. It took Western countries like Canada almost two centuries of fertility rate declines to reach replacement, whereas Bangladesh has done it in two generations. The second issue is whether countries that have high fertility rates, like Kenya (3.9), will slowly decline to the replacement rate. The figure below shows that the UN expects Kenya to reach this point at around 2060. Will this process take four decades? Bricker and Ibbitson don’t think so.

Figure: The UN's Total Fertility Rate Projects for Kenya

There are two key forces that cause fertility rates to plummet: urbanization and female education. Living in a city removes the economic incentive to have a large family. Children are another mouth to feed, cloth, and pay schooling fees for. Parents may want to have children for personal reasons, but unlike living on the farm, another child does not provide more net economic output for the household. Furthermore the social arrangements in urban areas are radically different from those of the country side. The power of the nagging grandmother and firebrand preacher hold more sway in rural areas where everyone knows everyone else. In the city family and religious pressure exists of course but it is diminished by increased economic opportunities and alternative social pressures stemming from coworkers and friends. The authors use the example of the cultural changes in Belgium as a useful case study of how fast things can change in a single generation.

In Belgium, attendance at mass on Sunday was nearly universal as late as the 1960s; today about 1.5 percent of the population in Brussels show up. The Catholic Administration in Belgium, one correspondent noted, “could become little more than a heritage agency for ancient churches.”

Women will go to any lengths to be able to control their own reproduction when given the chance. Literacy, the availability of outside employment, and access to contraception are all preconditioned on girls completing school. Fertility rates fall when female education increases because men can no longer treat women like breeding cattle. How exactly this works at an individual level is probably better summarized through stories and lived experiences but the data is clear: higher levels of female educational attainment lead to fewer babies.[3] Women already obtain higher levels of post-secondary education then men do in most countries. And while there is still a gap in the number of girls attending primary school in many poor countries due to cultural misogyny (i.e. the idea that it is better to educate the boys first), this number is falling overtime.

Fine, you may say, Bricker and Ibbitson could be correct and population growth will start to fall and the number of humans will begin to decline. Isn’t that a good thing given the worries around the environment? And furthermore, won’t that mean there are more jobs and life will be become easier and less competitive for the future generation? Won’t aging societies generally be nicer and more comfortable societies to live in, even if they are a little less dynamic? The first point is probably true. In 2500 the billion humans still around may look back and be glad that we voluntarily shrunk our population to save the planet. But Empty Planet want to make it absolutely clear its readers that the economic and social effects of a shrinking population will be a massive challenge for the humans who will be alive in the coming century.

Understanding how the economy works at a macro level can be difficult because micro experiences do not scale. For example, saving money is a good thing at an individual level. It allows one to retire comfortably and weather economic shocks. Therefore it seems like the more a society saves the better that society would be. But this is incorrect. If everyone tried to save 100% of their income, no one would buy anything, the economy would collapse, everyone would lose their job, and total savings would be $0. This is known as the paradox of thrift. An individual’s ability to save is not the same as the system’s ability to save. You are able to save money because someone else is not. The optimal amount of savings for a nation state is some positive number between 0% and 100%; but it is not a linear relationship.

At an individual level having a smaller family is an economic benefit. Having one or two children may cost a lot, but it is a manageable expense for a middle-class family. Imagine a society in which every woman only has one child at the age of 30. A pair of grandparents will have two children and one grandchild. Societies are able to provide public goods because most taxpayers are not users at any one time. When that grandchild turns 30, they have to support the high medical costs of their four grandparents at the age of 90 and the growing medical costs of their 60 year old parents. This paradigm creates a dilemma: one can support universal healthcare, pensions, and a tax level which is not crushing for the middle class or one can support having low fertility rates but not both. Anyone who is seriously concerned about spending cuts to healthcare must also be terrified of demographic trends.

For libertarians the aging population pyramid seems like a useful mechanism to cut government spending and reduce social transfers by forming new political coalitions with young voters. But an aging population will have consequences outside of government spending and even a libertarian’s idea of a paradise is unlikely to materialize. The reason that stocks and housing increase in value (on average) is because of population growth and productivity improvements through technology. Corporations are valuable because of the future goods they will sell. Land is valuable because of the future individuals who want to live on that land. Interest can be earned on savings because entrepreneurs have ideas and not money. What happens as the number of people with excess capital grows relative to individuals who want to borrow? Interest rates go to zero. Or worse. On August 2nd the entire German yield curve went negative. That is insane. Investors were willing to pay the German state for the privilege of holding 1 to 30 year bonds. Yet again the macro belies the micro. The entire foundation of positive returns on financial assets is based on the assumption of a balance between savers and borrowers. A contracting population puts massive downward pressure on investment returns. Every middle-class nest egg, whether it is made up of stocks, bond, or property, is at the mercy of demographic and economic forces beyond their control.

Can government policy encourage a higher population growth rate? The evidence is that there can be an effect on the margin, but once a society has seen fertility rates fall below 2.1, all government incentives to encourage fertility will at best move the needle towards 2.1, but never above it. The best thing countries like Japan or Italy could do to increase fertility rates would be to push for cultural and policy changes that allow women to both have a child and a fulfilling career. Developed countries which are relatively more patriarchal have the lowest birth rates because women know that when they get married, and especially when they have a child, they will be expected to sacrifice their career to mend their husband’s shirt and raise the children. In contrast women in relatively more egalitarian societies like Sweden know that if they have a child the husband will pitch in with paternity leave, do some housework, and return to a job after a year.

Some of those who fear the fallout of a diminishing population advocate government policies to increase the number of children that couples have. But the evidence suggests this is futile. The “low-fertility trap” ensures that, once having one or two children becomes the norm, it stays the norm. Couples no longer see having children as a duty they must perform to satisfy their obligation to their families of their god. Rather, they choose to raise a child as an act of personal fulfillment. And they quickly fulfilled.

But some Western will not experience the full weight of the inverted population pyramid because of one policy lever: immigration. In countries like Canada, that native-born grandchild needn’t pay for all of grandma’s healthcare because a highly-skilled Kenyan doctor will also be contributing income tax to the system and their grandmother will remain in Kenya and not receive Canadian-level medical care.

One solution to the challenge of a declining population is to import replacements. That’s why two Canadians wrote this book. For decades now, Canada has brought in more people, on a per capita basis, than any other major developed nation, with little of the ethnic tensions, ghettos, and fierce debate that other countries face. That’s because the country views immigration as an economic policy–under the merit-based points systems, immigrants to Canada are typically better educated, on average, than the native-born–and because it embraces multiculturalism: the shared right to celebrate your native culture within the Canadian mosaic, which has produced a peaceful, prosperous, polyglot society, among the most fortunate of the earth.

Europe’s recent migrant crisis has shown the variation in the tolerance to immigration between countries. Some countries like Germany and Sweden have accepted a significant number of refugees relative to their population. Others like Hungary and Poland have pulled up the draw bridge. The case of Bulgaria is illustrative. The country’s population has declined by 2 million persons from a peak of 9 million in 1989 to 7 million today. First the collapse of communism led the rural population to flock to the urban centers and then the country’s accession to the EU in 2004 led to an exodus of workers to other countries. Ever year Bulgaria’s population declines and the fertility rate stands at 1.5. And yet the country refuses to take refugees or immigrants. Deputy PM Valeri Simeonov said: “Bulgaria doesn’t need uneducated refugees… They have a different culture, different religion, even different daily habits… Thank God Bulgaria so far is one of the most-well defended countries from Europe’s immigrant influx.” Other European countries that have low birth rates and have opposed refugees and migrants include Greece (1.3), Italy (1.4), Romania (1.3), and Slovakia (1.4).

These countries are already losing population. Greece’s population started to decline in 2011. Fewer babies were born in Italy in 2015 than in any year since the state was formed in 1861. That same year, two hundred schooled closed across Poland for lack of children. Portugal could lose up to half its population by 2060. The united Nations estimates that the nations of Eastern Europe collectively have lost 6 percent of their population since the 1990s, or eighteen million people.

Is it racist for a country to wish to maintain ethnic homogeneity despite the economic costs? If so, Eastern Europe is hardly alone. Countries like Japan (1.4), South Korea (1.2), Singapore (1.2), Hong Kong (1.1), and mainland China (1.6) (fertility rate shown in brackets) effectively take zero refugees. The statistics are almost comical. Canada has 4.2 refugees per 1000 persons, whereas the previously cited countries have 0.02, 0.03, 0, 0.02, and 0.2.[4] The percent of the population which is foreign born is very low for South Korea (2.9%), Japan (1.1%), and China (0.1%).

In a world where the native-born population is declining in wealthy countries and holding stable in low- to middle-income countries, immigration policy becomes geopolitical. By the end of this century, China’s population may be as low as 700 million (half of what it is today), whereas the United States is on track to exceed 400 million. Does anyone really think that China could be the global hegemon if its population halves? Countries like the US and particularly Canada will be able to draw in the world’s smartest and most socially useful migrants (think nurses) to their countries. This will both boost their national populations and help to smooth out the population pyramid. Canada could have a population of 100 million by the end of this century if we maintain or increase our yearly migration rates. Our country could have twice the population of Germany or the UK in 80 years. There is a national security argument that to protect the liberal democratic order countries that have strong civic, rather than ethnic, identities need to bolster their populations through immigration before the global population peaks and then begins to decline. If the hypothesis of Empty Planet is true then the politics of immigration will be one of the most important factors determining the global balance of power in the 21st century.

-

There are some exceptions to this rule. There may be a rare mineral that has only grams of material in the entire crust of the Earth or their could be a wartime situation where the opposing power is seeking to remove access to some resource that a warring power imports entirely. ↩

-

One does not usually think of mullahs as encouraging birth control. ↩

-

This statement is only true in countries that are at or above the replacement rate. In contrast, women with a college degree who live in wealthy countries like the United States may actually have more children because they are more likely to be married and in stable economic arrangements. ↩

-

For example Singapore had 59 refugees in 2014 out of a population of 5.6 million. ↩