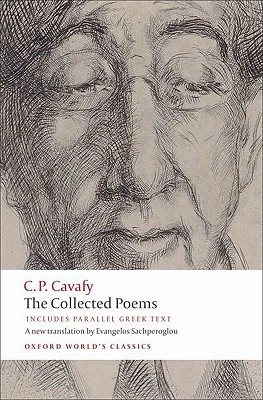

The Collected Poems of C.P. Cavafy (Book Review)

There are a handful of authors whose works have the feeling of being sui generis. I have in mind El Greco’s psychedelic paintings, Mervyn Peake’s gothic flights of fancy, or Italo Calvino’s post-modern fairy tales as examples. Surely C.P. Cavafy[1] deserves to be on the list as well. No description of Cavafy may begin without reference to E.M. Forster’s famous quote describing the man as:

A Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.

Cavafy belonged to that class of artist whose identity was inextricably linked to the city in which their art was produced.[2] Born in Alexandria in 1863, Cavafy would spend the majority of his life in the city of his birth. His existence would always be one on margins of society, first as a Greek Orthodox Christian living in the Muslim-majority state of Egypt, and second as a homosexual. It becomes clear after reading one or two of Cavafy’s homoerotic poems that his personal life was the source of inspiration for much of his work. Cavafy’s poems fall into two categories: Eros and Historical. The former are often sad and haunting, rife with loneliness and sexual frustration. The latter tells stories from forgotten periods Hellenistic history. Though Cavafy’s poems are easily dichotomized, similar themes and yearnings can be felt in both of them.

The Collected Poems of Cavafy from Oxford World Classics spans a little more than 200 pages, including the introduction and footnotes. This collection, translated by Evangelos Sachperoglou, also contains the original Greek running side-by-side with the English on the right-hand side of the page. The more I learn about Cavafy’s poems the more I empathize with the translator and feel sadness that my monolingualism necessitates that I miss much of its Greek subtleties. Translating poetry has always been a difficult art due to complexities around rhyme scheme and meter. Not only do Cavafy’s poems contains rhymes, which are lost in English translation, they also contain the use of both classical and Demotic Greek. According to Daniel Mendelsohn, author of Cavafy’s Complete Poems, in The Seleucid’s Displease (or The Displeasure of the Seleucid in my volume), Cavafy uses Katharevousa (i.e. classical Greek) the first time the word begging is used, and then switches to the demotic in the second, to indicate the decline in status of the Greek Ptolemy. Here is the Mendelsohn translation:

But the Lagid, who had come a mendicant

knew his business and refused it all:

…

And then he presented himself to the Senate

as an ill-fortuned and impoverished man,

that with greater success he might beg.

Contrast that to the Sachperoglou translation:

But the Lagid, who had come intent on begging,

knew his business and refused it all;

…

And later on he appeared before the Senate

as a wretched person and a pauper,

thus more effectively to beg.

While Mendelsohn tries to indicate this change in linguistic hierarchy through the English equivalent of a high-brow Latinate word (“mendicant”) in contrast to the more guttural Anglo-Saxon (“beg”), Sachperoglou attempts to change the tone through the choice of words preceding beg (“wretched”, “pauper”). Though it is impossible for me to assess the literal quality of the Greek translations, my sense is that The Collected Poems presents Cavafy’s works styled in a more traditional artistic form of poetry, more akin to Shakespeare. For example, consider this somewhat halting line from The City:

You said: ‘I’ll go to another land, I’ll go to another sea.

Another city will be found, a better one that this.

While Mendelsohn’s version comes off as much more naturalistic:

You said: “I’ll go to some other land, I’ll go to some other sea.”

There’s bound to be another city that’s better by far.

Readers will need to decide for themselves which stylistic form is to their liking. The image one has of Cavafy inevitably colours the reading of his work. This is somewhat ironic given that the author never directly refers to himself in any of his poems (even if many of the Eros ones are autobiographical). Can one still imagine Cavafy living in his squalid Alexandrian apartment above a brothel when reading the historical vignettes of the ancient Greek world? In dreaming of the melancholy wedding of Byzantine emperor John Cantazuzenus, who dons a fake crown – the real one having been sold to pay for the empire’s debts (Of Coloured Glass) – we cannot help but see a glimpse of Cavafy’s aestheticism showing through. In another, we hear of the yearning of Demetrius Soter to return to Syria only to have his kingdom once again stolen by the false pretender Alexander Balas (Of Demetrius Soter). Cavafy, living in a provincial town, once formerly the most splendid in the Greek world, can surely empathize.

For most Western readers, “Greekness” (i.e. Hellenism) is made up of two discontinuous periods: the ancient Greek world of Homer and Pericles, and then after a 2000 year gap, the revival of the Greek nation state after independence from Ottoman control. In contrast, Cavafy’s sense of Hellenism is more akin to Judaism: an unbroken cultural chain that was preserved through the Alexandrian kingdoms and the Greek colonies in Asia Minor and the Mediterranean. While Greek power went into decline after the Battle of Actium when Ptolemaic Egypt was conquered by Imperial Rome, Greek culture was preserved in the Eastern Roman Empire through the Byzantines. Even after the fall of Constantinople, Greeks continued to have a unique identity and role in the Ottoman empire, mainly as a merchant class. Greeks were also in charge of Christian spiritual affairs, with the Phanariot Greeks controlling the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Until the 1920s, Greeks were a large minority in Turkey, although the tragic “population exchanges”, more akin to ethnic cleansing, destroyed communities that were a thousand years old in the 1920s. In Cavafy’s era, the Greek community in Alexandria felt as Greek as Greeks living in Athens or the Greeks that lived in Smyrna. It is interesting to note that Cavafy only travelled to Greece once in his life, and that was to receive treatment for his laryngeal cancer to which he would eventually succumb.

The City

My favourite of Cavafy’s poems, The City conjures up that delicious feeling of inexorable decline, mercilessly dictated by the three sisters of fate. For a city like Alexandria which conjures up the glories of the past – Alexander the Great, the Ptolemies, Caesar and Cleopatra, the eponymous library – its decline is especially poignant. Cairo had long since displaced Alexandria as the administrative capital of Egypt after Ottoman annexation. Much like Venice today, those living in Alexandria had to compare the banalities of their daily life to the imagined splendour that others had of their city’s existence.

You said: ‘I’ll go to another land, I’ll go to another sea.

Another city will be found, a better one that this.

My every effort is doomed by destiny

and my heart–like a dead man–lies buried.

How long will my mind languish is such decay?

Wherever I turn my eyes, wherever I look,

the blackened ruins of my life I see here,

where so many years I’ve lived and wasted and ruined.’Any new lands you will not find; you’ll find no other seas.

The city will be following you. In the same streets

you’ll wander. And in the same neighbourhoods you’ll age,

and in these same houses you will grow grey.

Always in this same city you’ll arrive. For elsewhere–do not hope–

there is no ship for you, there is no road.

Just as you’ve wasted your life here,

in this tiny niche, in the entire world you’ve ruined it.

Perhaps Cavafy found this inescapable geographic identity as somewhat of a relief given his personal circumstances: confined to his Alexandrian prison he could live in the past. And not just the triumphant past of Periclean Athens or Imperial Rome but on the margins of antiquity; of forgotten Byzantine emperors and Syrian kings.

Political organization

For readers with a more analytical mindset, Cavafy’s poems have a surprising political sophistication to them. Cavafy appears to have read history, not only with an eye to the pathos which artists are naturally inclined towards, but to those subtle forms of political organization and power. In one of my other favourite poems, Waiting for the Barbarians, Cavafy captures a Gibbon-like decline in institutional capacity that renders the state paralysed to handle an external military threat. We learn that the emperor, senators, and praetors have already resigned themselves to be conquered by the barbarians. Yet at the end of the poem, when all are made aware that the barbarians are no longer coming, the rot is revealed as coming from within:

And now, what will become of us without barbarians?

Those people were some sort of a solution.

The Khedivate of Egypt which Cavafy grew up under was nominally independent, but overtime it became more akin to a puppet state of the British. Ismael Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt from 1863 to 1879, undertook a massive campaign of public spending that eventually bankrupted the country. The British and French restructured debt payments, but in turn took control over the country’s finances. One wonders whether Egypt’s financial embarrassment may have influence Cavafy’s delightful poem In a Large Greek Colony, 200 B.C.

That the affairs in the Colony are not going well

not the slightest doubt remains,

and though somehow or other we are moving along,

perhaps, as many believe, the time has come

to bring in a Political Reformer.But the obstacle and the difficulty is,

that these Reformers make

a great issue out of everything.

(A blessing it would be if nobody

ever needed them.) They examine

and inquire about the slightest little thing,

and they set their mind immediately on radical reforms,

demanding that these be executed without delay.And when, in good time, they complete their assignment,

and having specified and reduced everything down to the last detail,

they depart taking away their rightful wages,

then let us see what else is left

after such surgical dexterity.Well, possibly the time may not, as yet, be ripe.

Let’s not be hasty; rashness is a hazardous thing.

Untimely measures foster regrets. To be sure,

there is, unfortunately, a lot that’s out of place in the Colony.

But is there anything human devoid of imperfection?

And, well, one way or another we are moving along.

Classical signalling

Some of Cavafy’s more light-hearted poems were those that took place during eras in which the use of Greek culture was a signalling device for the elites. In Philhellene, the king of some backwater Greco-Persian kingdom dictates to an engraver to ensure his love of Greek culture is preserved for posterity.

See to it the engraving be skilfully done.

The expression serious and dignified.

The diadem preferably rather narrow;

those broad Parthian ones are not to my liking.

The inscription, as usual in Greek;

nothing excessive, nothing pompous–

lest the proconsul, who always pokes around

and reports to Rome, take it the wrong way–

but nonetheless, of course, honorific.

Something very special on the other side;

some handsome youth, a discus-thrower

Above all, I bid you pay attention

(Sithaspes, in god’s name, don’t let this be forgotten)

that after the words ‘King’ and ‘Saviour’

be engraved in elegant lettering: ‘Philhellene.’

And now don’t start your witticisms on me,

like: ‘where are the Greeks’ and ‘where is Greek used

around here, this side of Zagros, way beyond Fraata.’

Since so many others, more barbarous than we,

write it, we will write it too.

And finally, do not forget that on occasion

there comes to us sophists from Syria,

and poetasters and other pretentious pedants.

Thus, we are not lacking in Greek culture, I do believe.

The last line is particularly amusing as the king is sufficiently ignorant to know whether or not his Kingdom’s claims to Grecian sophistication are true or false. In For Ammones, Who Died Aged 29, in 610, a fictitious Alexandrian by the name of Raphael is asked to compose a poem, in Greek, for another fictitious poet name Ammones. Though Raphael is not a native Greek speaker, it is believed that he is the most skilled at constructing poems in a passable Greek manner. The title of the poem also hints at the linguistic politics of the Byzantine empire, as this was the year that the emperor Heraclius changed the language of the court from Latin to Greek.

Raphael, they want you to compose a few verses

as an epitaph for the poet Ammones.

Something polished and in good taste.

You can do it, you are the apporpriate person to write

as befits the poet Ammones, our very own.You must, of course, mention his poems–

but your should also speak about his love of beauty,

his delicate beauty we loved.Your Greek has always been elegant and musical.

But we’re in need of your entire skill now.

Our love and our sorrow pass into a foreign tongue.

Pour your Egyptian feeling into the foreign tongue.Raphael, your verses must be written in such a way

that they contain, you know, something in them of our lives,

that both cadence as well as every phrase denote,

that an Alexandrian is writing about an Alexandrian.

Other poems

Cavafy was no doubt attracted to rituals and aesthetics of Orthodox Christianity; in the same way that the Catholic church continues to hold a similar appeal to many contemporary gay men (despite the Church’s continued official homophobic doctrine). In Supplication, we imagine the solace and false comfort provided by the iconography of Mary to a distressed mother.

The sea took a sailor into its depths.–

His mother, unware, goes to lighta tall candle before the Virgin Mary,

that he return soon and meet with fine weather–all the while turning windward her ear.

But as she prays and supplicates,the icon listens, solemn and sad, well aware

that he’ll never come back, the son she awaits.

The style and texture of this poems actually reminds me of Tennyson’s Canto VI of In Memoriam.

O mother, praying God will save

Thy sailor,—while thy head is bow’d,

His heavy-shotted hammock-shroud

Drops in his vast and wandering grave.

It is completely conceivable that Cavafy had read Tennyson’s poems, the former being fluent in English after living in England for several years, and the latter being one of England’s most famous poets during the Victorian Era. Though the icon of Supplication is mute and sympathetic, the dark demon in Kleitos’ Illness is not.

Kleitos, a likeable young man,

about twenty-three years old–

with excellent upbringing and first-rate Greek learning–

is gravely ill. He caught the fever

that swept through Alexandria this year.And an old servant woman who had raised him

is trembling too for the life of Kleitos.

Deep in her terrible distress,

an idol comes to her mind, which she worshipped

as a girl, before she entered there, a servant

in the home of prominent Christians, and converted.

She discretely takes some unleavened cakes, wine and honey.

She puts them before the idol, intoning those chants

of supplication she still remembers: bits and pieces. The fool!

She doesn’t realize that the dark demon couldn’t care less

whether a Christian were to get well or not.

Several of Cavafy’s poems are set in the theologically liminal space of early Christianity. In the case of Kleitos’ Illness, the old pagan gods retain a spiritual hold on the world; their curses still having some effect on the well-being of mankind. I found Myres: Alexandria, A.D. 340 to be one of the best examples of the mixture of Cavafy’s Eros and Historical poems, although it formally belongs to the latter. Similar to the previous poem, it takes place in a time when Christian and pagan cultures lived together, although the latter had sown the seeds of its ascendency through its hostility to traditional customs. Not only does the narrator mourn for the loss of his friend, he now sees a chasm between himself and a Christian world he is unable to cross over to. Like many of Cavafy’s Eros poems, the poet mourns of the loss of a “beautiful youth”.

We knew, of course, that Myres was a Christian.

We knew if right from the start, when

he joined our group of friends two years ago.

But he led his life exactly as we did.

More given to sensual pleasures than any of us,

squandering his money lavishly on amusements.

Oblivious of his reputation in society,

he threw himself readily into nocturnal street-brawls,

when our group of friends chanced

to encounter a hostile company.

He never spoke about his religion.

As a matter of fact, we told him once

that we’d take him with us to the Serapeum,

but he appeared displeased

with this little joke of ours: I remember now.And suddenly I was overwhelmed by an eerie

awareness. Vaguely, I felt

as if Myres was drifting away from me;

I felt that he, a Christian, was being united

with his own kind, and I was becoming

a stranger, a total stranger; I could already feel

a certain ambivalence closing in: was it possible I’d been misled

by my passion, that I had always been a stranger to him?–

I hastened out of their dreadful house;

I left in a hurry, before their Christianity could snatch away,

before it could distort the memory of Myres.

The last poem I will make a highlight of, Come Back, captures the erotic nostalgia of Cavafy’s long-ago encounters. For the poet, love is a past that can be resurfaced through the right repetitions, like an incantation.

Come back often and take hold of me,

beloved sensation, come back and take hold of me–

when the memory of the body is aroused,

and past desire flows into the blood again;

when the lips and the skin remember,

and the hands feel as it they are touching again.Come back often, and take hold of me in the night,

when the lips and the skin remember.

Reading this hauntingly sad poem reminded me of the beautiful Canto L from In Memoriam.

Be near me when my light is low,

When the blood creeps, and the nerves prick

And tingle; and the heart is sick,

And all the wheels of Being slow.