The Gene by Siddhartha Mukherjee (Book Review)

Introduction

The Gene is Siddhartha Mukherjee’s second book following The Emperor of All Maladies[1], which won the Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction in 2011 for chronicling the history of cancer. Like his first book, The Gene seeks to tackle the whole history of the subject, which in this case means parsing the state of genetic knowledge from homunculus to the human genome project. Both books are written in the same style with the chapters broken up into small vignettes. As an oncologist Dr. Mukherjee had the added benefit of being able to link the theoretical issues and concepts of cancer to his actual patients in the first book. In The Gene, Mukherjee maintains a similar level of intimacy with the reader by describing the various mental health issues that have run throughout his father’s side of his family. From a writer’s perspective, it is interesting that one would write about a specific genetic disease first, and then about genetics second, as one may assume that conceptual specificity follows generality. However, for the Mukherjee oeuvre, the ordering is well suited. Mukherjee’s knowledge of oncology stood on the shoulder of genetics and it is only fitting he play the reductionist in this second work after gazing over the landscape from his perched view.

Three ideas which underpin our understanding of the material world came to full fruition in the twentieth century: the atom, the bit, and the gene. While we had some ur-idea of each of these concepts in preceding centuries, they were only flushed out in the twentieth. These three conceptual units provided the most functionally appropriate level of study for their respective fields (physics, computer science, and biology). While modern biology needs an understanding of evolution to explain why we see the variety and frequency of biological forms that we do, even at a give snapshot in time, the gene is required to explain how biological forms work and reproduce. In this sense, even a creationist would have wondered how it was that all this ‘biological stuff’ actually works. The question of ‘what is life’ would perplex and challenge earlier generations until a modern synthesis of ideas came together in cell and molecular biology.

From the Greeks to the Enlightenment, science was largely driven by intuition and logic to unravel nature’s mysteries. With almost terrifying precision Newton was able to figure out the most important laws of physics and calculus by ruminating in a (probably stuffy) room in Cambridge. And yet, there are some problems to which ‘philosophizing’ proves insufficient. However, 19th century laid to rest that idea that human intuition and logic went hand-in-hand with the natural world. Instead science could now be based on following the implications of models which had already shown themselves to be accurate predictors of physical reality, despite the their seeming incongruity.[2] Christian Doppler, one of Mendel’s physics teachers incidentally, shocked audiences by having brass players demonstrate the Doppler effect: sound coming towards you sounds different that sound moving away from you. Ironically, the very reason that we find many physical phenomenon hard to understand,[3] is because of a concept we find hard to understand: evolutionary psychology (which tells us that our brains are wired to understand things that were important for our species’ evolutionary fitness like the parabolic arcs of thrown objects).

(i) What the ancients thought

Appearances of “likeness” between parent and sibling did provide one intuitive link between sex and genetics however. Pythagoras of Croton thought that semen carried the self-information of the male into the next generation by coursing through the body and taking note of all the body’s key attributes (on miniature papyrus no doubt). Once inside the womb, the woman would provide nourishment. Gender roles at the zygotic level were nicely segregated and matched social expectations. Pythagorean genetics were on display in Aeschylus’ Eumenides where Apollo defends Orestes for the murder of Clytemnestra.

(Chorus) He who hath shed a mother’s kindred blood,

Shall he in Argos dwell, where dwelt his sire?

How shall he stand before the city’s shrines,

How share the clansmen’s holy lustral bowl?

(Apollo) This too I answer; mark a soothfast word:

Not the true parent is the woman’s womb

That bears the child; she doth but nurse the seed

New-sown: the male is parent; she for him,

As stranger for a stranger, hoards the germ

Of life, unless the god its promise blight.

Plato believed that since children were some function of their parents attributes the possibility of good breeding (eugenics) could improve the calibre of the republic’s citizens. Aristotle rejected the previous Pythagorean idea that only the male’s attributes were germaine to genetics. He accurately noted that both the mother and father’s characteristics were present in offspring and that phenotypes can skip a generation (a phenomenon which helped Mendel to distill his thinking): “In Sicily a woman committed adultery with a man from Ethiopia; the daughter did not become an Ethiopian, but her granddaughter did”. He correctly pointed out that if the sperm collected the current attributes of the male, how did young men pass traits to their children (such a greying hair) which they themselves had not yet experienced? Instead, Aristotelian genetics posited that male’s provides the message whilst female’s furnished the material. As Mukherjee puts it:

Aristotle was wrong in his in partitioning of male and female contributions into “material” and “message,” but abstractly, he had captured one of the essential truths about the nature of heredity. The transmission of heredity …. was essentially the transmission of information. Information was then used to build an organism from scratch: message became material.

However, even attaining a conceptual framework begs the further practical question:

[I]f heredity was transmitted as information, then how was that information encoded? The word code comes from the Latin caudex, the wooden pith of a tree on which scribes carved their writing. What, then, was the caudex of heredity? What was being transcribed, and how? How was the material packaged and transported from one body to the next? Who encrypted the code, and who translated it, to create a child?

Medieval and Renaissance thought in Europe gravitated towards the idea of preformation, that is that miniature humans were to be found inside sperm. In addition to being intuitive, theologians found pleasing the implication that the material which made up our bodies could literally be traced back to the original sin, forever binding our fate to the fall of man.

Humonculus: A tidy idea of heredity

(ii) The modern age of genetics

Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian Friar and amateur scientist, single-handedly determined that genetic information in sexual reproduction was inherited in two discrete genes. The idea that genetic information was that, pieces of information, was essential to understand not just genetics (of course) but evolution and biology as well. Darwin had struggled with explaining the “variability of organic beings in a state of nature” with his idea of pangenesis, essentially a riff on Pythagoras’ idea that the sperm collects information from each part of the body, except Darwin had replaced “body” with “cells”. However, pangenesis was also an endorsement of the Lamarckian view of genetics which held that transformations to the adult body could be passed onto their children.[4] In 1883 however, the German embryologist August Weismann performed the grimly methodical experiment of removing the tails of 901 mice and measuring the tail lengths of their offspring. There was no difference: Lamarckian genetics was dead.

This needn’t have been a problem as Mendel had already discovered an alternative set of laws of heredity which accurately described the relationship between inherited characteristics in pea plants. Unfortunately, in a truly heartbreaking episode of scientific history, Mendel was ignored by his colleagues and his groundbreaking paper Experiments on Plant Hybridization was confined to the dustbin of the Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn in 1865. Not only was genetics set back at least thirty-five years (Mendel’s findings would be rediscovered at the turn of the century), but Darwin was deprived of a theory at exactly the time he needed one to explain the variability of natural forms within and between species.

The rebirth of genetics was lead by a handful of figures including the Dutch botanist Huge de Vries. In his 1897 paper Heredity Monstrosities de Vries identified that the inheritance of traits in his data could only be explained by a “single particle of information”. But de Vries went further than Mendel is describing a feature of inheritance that was not found in either of the parents genetic information: mutants (a term coined by de Vries which means ‘change’ in Latin). In other words de Vries showed that:

\[\text{Child's traits} = f(\text{Mother's traits}, \text{Father's traits}) + \text{mutation}\]This was the piece of the puzzle that Darwin was missing. Giraffe’s necks did not get longer over time because they continued to stretch their necks, but rather because those animals who had mutations which led to larger necks had enhanced evolutionary fitness.[5] While Darwin was struggling to pin down a theory which could synthesize evolution by natural selection and a genetic mechanism for propagating traits, his cousin Francis Galton was looking for statistical evidence that human characteristics were actually being passed down. Galton was undoubtedly influenced by Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian Statistician who pioneered ‘social physics’,[6] and showed that many social and physical phenomenon (crime rates or chest size for example) followed statistical distributions in the population as a whole. Galton wanted to show that genius was hereditary,[7] and he found that:

[A]mong the 605 notable men that lived between 1453 and 1853, there were 102 familial relationships … If an accomplished man had a son, Galton estimated, chances were one if twelve that the son would be eminent. In contrast, one one in three thousand “randomly” selected men could achieve distinction… Lords produced lords–not because peerage was hereditary, but because intelligence was.

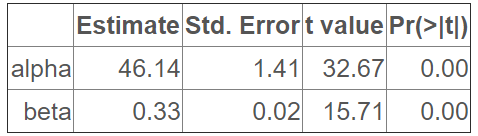

Of course, Galton understood that this may be because of social advantage and coined the expression “nature versus nurture”. However, he sided with nature in the case of the peerage. While most of what Galton said was wrong he helped us understand the nature of statistics and genetics better by the mistakes he made. Galton also coined the term regression because he found that only a ‘fraction’ of the height of the parents in their offspring. Using a data set which had the height of 934 children and their parents, (he converted the height of the female children to the 1.08 times their height which was the ratio of the of difference in the sex-specific height means he found in the sample),[8] he ran the following regression and found:

\[\text{offspring} = \alpha + \beta \cdot \text{parent} + u\]

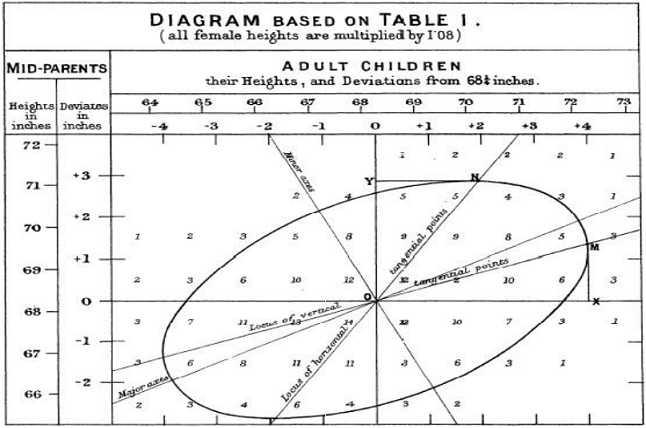

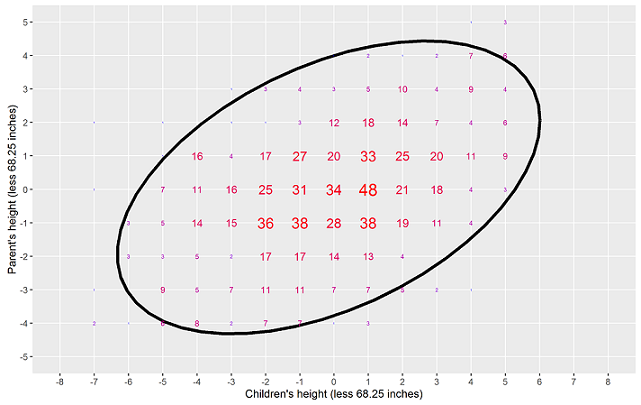

As anyone with knowledge of infinite sequences knows, $ \lim_{t \to \infty} { \text{offspring}_t } = \frac{\alpha}{1-\beta} $ which means that Galton’s model suggested in the long-run (sex-adjusted) height will return to 68.4 inches, the same mean height of the parents in the sample. Further evidence for the ‘reversion’ phenomenon was by plotting a confidence ellipse on the bivariate data and to notice that the 45 degree line intersected it a ratio of around two-thirds of children to parents height, as shown in Chart 1 in Galton’s original paper.

Chart 1.A: Galton's original figure

Chart 1.B: Replication of Galton's data

Galton possessed an impressive amount of intellectual zeal, but his impatience led him to overgeneralize his findings and seek to describe the most complex phenomena whilst even systems remained conceptually obscure. As noted above, Galton found the logic of infinite series appealing and posited that the inheritance of features resembled the following geometric series: $ \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + … $. In other words Esau begat half of Reuel who begat half of Zerah and so on. To reinforce his putative achievement he jumped straight from a hypothesis to Galton’s Ancestral Law of Heredity. Whilst data from the Basset Hound Club Rules on the color of dog’s coats initially lent credence to Galton’s views, a more rigorous inquiry into other sources provided by William Bateson, an early geneticist, proved that Galton was wrong and Mendel was right.

[H]ereditary instructions were carried by individual units of information, not by halved and quartered messages from ghostly ancestors. A child was an ancestral composite, but a supremely simple one: one-half from the mother, one-half from the father. Each parent contributed a set of instructions, which were decoded to create a child.

With the conceptual idea of modern genetics firmly understood by the first quarter of the 20th century, the scientific community would begin to ask what was the actual mechanism of inheritance? Was the transmission of life a process able to be understood by science, or did biology possess a special spark invisible to lens of empirical inference?

Footnotes

-

Referred to as TEoALM from here on out. Note, TEoALM was was one best books I have ever read, one of the few non-fiction books I have read twice, and one additional spur to switch out of the field of Economics to Biostatistics. ↩

-

Although interestingly this idea of looking at only results rather than hypotheses was included in Osiander’s prologue to Copernicus’ De revolutionibus: “… it is the duty of an astronomer to compose the history of the celestial motions through careful and expert study. Then he must conceive and devise the causes of these motions or hypotheses about them. Since he cannot in any way attain to the true causes, he will adopt whatever suppositions enable the motions to be computed correctly … The present author has performed both these duties excellently. For these hypotheses need not be true nor even probable. On the contrary, if they provide a calculus consistent with the observations, that alone is enough … For this art, it is quite clear, is completely and absolutely ignorant of the causes of the apparent [movement of the heavens]. And if any causes are devised by the imagination, as indeed very many are, they are not put forward to convince anyone that they are true, but merely to provide a reliable basis for computation. However, since different hypotheses are sometimes offered for one and the same … the astronomer will take as his first choice that hypothesis which is the easiest to grasp. The philosopher will perhaps rather seek the semblance of the truth. But neither of them will understand or state anything certain, unless it has been divinely revealed to him … Let no one expect anything certain from astronomy, which cannot furnish it, lest he accept as the truth ideas conceived for another purpose, and depart this study a greater fool than when he entered.” ↩

-

Very small things (i.e. bacteria), very large things (i.e. galaxies), very fast things (i.e. light), and very slow things (i.e. evolution). ↩

-

For example, Lamarck thought that the long necks of giraffes had evolved because some giraffes which had stretched their necks were more successful and had passed on this trait. However Lamarckian genetics confused phenotypes with genotypes, assuming that the former drove the latter, rather than the other way around. From a utilitarian perspective though, the belief in Lamarckian genetics may be a positive motivating force for individuals to apply physical and intellectual exertion in the belief that their achievements will be passed onto the next generation. ↩

-

Fitness in the evolutionary sense refers to the propensity of certain genetic traits to increase the change of offspring. ↩

-

A term which now in use again thanks to an MIT Lab of the same name which hopes to use Big Data to explain… everything? ↩

-

Galton was related to Charles and Erasmus Darwin… coincidence? Francis thought not! ↩

-

Note, a very similar relationship is found is one takes average of the individual family ratios of average male to female height. Such a check may be useful in case say shorter families have fewer girls (possibly for epigenetic reasons). ↩