A Brief History of Medicine by Paul Strathern (Book Review)

Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place. (Susan Sontag – Illness as Metaphor)

One of Sam Harris’ propositions is that morality can be derived from scientific principals if one accepts one axiom as a given: the universe in which all sentient life experiences the most extreme and tortuous discomfort during their lives is the worst universe. Working backward from this, Harris goes on to say that to evaluate states of pain or comfort we need to use science and therefore states of the universe can be morally compared through empirical deduction.[1] He often receives the retort that how can we be sure what “discomfort” or “suffering” really are? His response is that these terms are of course tricky to pin down, but that we accept definitional ambiguity in other domains of knowledge such as medicine. While health is a tricky concept to pin down too, surely we would agree from common sense that vomiting every day is less healthy than not, correct? But how did we come to understand that vomiting is a symptom of some specific underlying pathology or that swelling is an immune system response? Paul Strathern’s Brief History of Medicine tackles this topic in short and punchy chapters. Note that the title is more ambitious that the actual book, as this is really a guide up until the 20th century. While he does make mention of the discovery of genes and the possibilities of personalized medicine, this book should really be titled: Medicine: From Hippocrates to Pasteur.

Strathern attributes the beginning of modern medicine to William Harvey’s demonstration of the principals which regulate the circulatory system. It is one the first examples in the history of medicine of what I called kuhnfreude[2] (the discovery that the beliefs of the revered ancients were utter bunk) when Harvey publishes De Mort Cordis (concerning the motions of the heart) and writes: “I straightways found it a thing hard to be attained, and full of difficulty, so … I did almost believe that the motion of the heart was known to god alone.” Indeed, before Harvey we had taken Galen and Hippocrates’ word that blood was continuously created in the liver (discussion of who these men were is found below). This is one of the first of many discoveries that will slowly turn medicine away from its state of knowledge at the time of Marcus Aurelius towards something recognizable today.[3]

However, before the application of modern scientific principles to the human body, a proto set of medical knowledge was developed by the ancients. While almost all of the ideas were nonsense, they at least laid down a rational way of applying logic to building a body of medical information and provided falsifiable hypotheses that were later debunked. The ancient Greeks believed that medicine traces its origins back to Asclepius who was the son of Apollo, and he was symbolized by a staff – where we still have the symbol of the staff of Asclepius in medicine (although unfortunately Zeus killed Asclepius as he became concerned that he was raising humans from the dead).

Our first figure in the history of early medicine is Hippocrates (alive during the 4th and 5th century BCE) and well known in the eponymous oath taken by doctors to this day. While he believed that all diseases stemmed from an imbalance of ‘humors’, he also set the groundwork for modern medicine by stating that all pathologies had material causes. For example, in his time epilepsy was believed to be caused by spiritual forces taking control of human beings. However, Hippocrates believed that epileptics suffered from an excess of phlegm, and were convulsing to ‘clear out the passages’. While this was a bit off the mark, the theory laid itself open to a material disproof: a feature of enlightenment science. The political economy of the Hippocratic Oath is quite interesting too as it was an excellent example of licensing to ensure a less elastic supply of labour: “I will not cut, even for the stone, but I will leave such procedures to the practitioners of that craft”. In addition to separating the professions of ‘physicians’ and ‘surgeons’, it helped to cement a class division that practical tasks were inferior to the role of the physician which was to use only knowledge and thought (another unhelpful innovation). While it may pale in comparison to his other accomplishments, Hippocrates Aphorisms also have survived throughout the ages, with the following delight: “Life is short, art is long; opportunity elusive, experience fallacious, and judgement difficult.”

However, the early Greek physicians were not just laying important groundwork for empirical discovery later in time whilst attributing everything to a surplus of phlegm, they were also discovering actual properties of the human body by asking novel questions and actually analyzing the human body. Take Herophilus, often ascribed as the father of anatomy. He was the first person to record the dissection of the eye and document the retina as well as the small intestine and the prostrate! He may have also been the first to record the pulse of the human heart using a water clock. His pupil Erasistratus was also the first person to identify the nervous system and identify the difference between sensory and motor nerves, as well as performing brain dissections to see that the large cerebrum encloses the smaller cerebellum. It’s amazing what happens when one has the intellectual curiosity to open up the human body and ask: what’s going on in here?

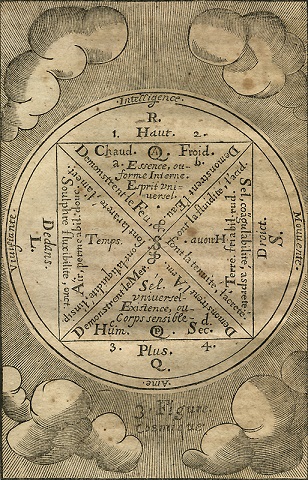

The man who did more than any person in history to establish the tradition of medical knowledge was Galen, a Greek born in Pergamum that moved to Rome where he become a medical celebrity (Marcus Aurelius described him as “primum sane medicorum esse - first among doctors”). Galen’s genius was to map Hippocrates’ four humors with Aristotle’s four elements[4] to a simple compass-like schematic (see below) which explained all diseases. The intellectual success of the schema was why, for example, blood-letting was common into the 19th century as a surfeit of blood was believed to cause certain conditions. Galen’s impact of the intellectual history of medicine cannot be understated, and he was such as prolific writer that over 20,000 pages of his works survive to this day.

Like most of other works of antiquity, the writings of Galen and Hippocrates were kept in safe keeping and even expanded upon by the Arab world throughout the European dark ages. At the height of the Islamic enlightenment, the religious view was that Allah does not create a disease that there is not a subsequent cure to discover (an optimistic theology). Al-Razi was a doctor who trained in Baghdad’s bimaristan – “a home of the sick” where he eventually published the Comprehensive Book of Medicine. While a great fan of Galen, al-Razi was able to show that some of Galen’s principles were unsound (such as a human body can only get warmer is a hot liquid is drunk) by an improved understanding of chemistry.

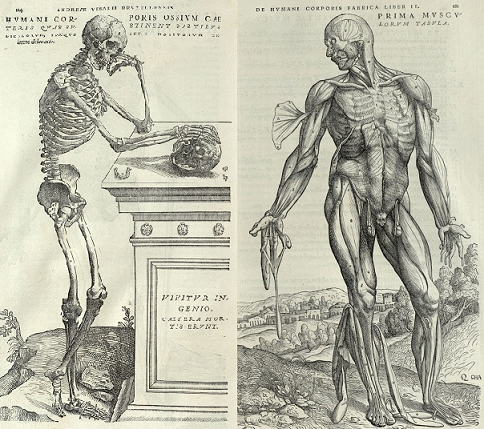

The survival of Greek and Roman medical works through Islamic scholarships allowed their rediscovery during the enlightenment at which point men like the Flemish physician Vesalius would help draft the layout for a new science. His masterwork, De Humani Corporis Fabrica contained 200 folio illustrations from bone to muscle layers. Even today the illustrations by Johannes Stephanus are beautiful to look at (see below), and we have the inhabitants of the Cemetery of Innocents in Paris to thank for their posthumous contribution. Like so many important persons who advance science, their legacy extends to their pupils, and Vesalius’ student Gabrielle Fallopius was the first to take a detailed undertaking of the study of female generative organs. Indeed fallopian tubes, the placenta, and the vagina are all terms Gabrielle provided us with. Unlike cartography where discovers use the names of friends and family members to label every shoal and rock, Vesalius mainly stuck to using Latin and Greek words to title new medical discoveries.

Some beautiful sketches by Stephanus

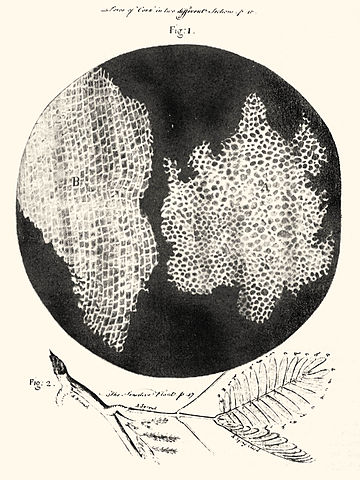

It seems likely that the initial burst of medical discoveries could be attributed to the “low hanging fruit” grown from a cultural taboo on actually opening up the human body for almost 1500 years. However, since the biological kingdom is united by a functional unit, the cell, it would require a further level of reductionism for medical science to continue to advance. The development of modern optics that helped Copernicus and Galileo explain the heliocentric reality of the universe eventually spilled over into the development of microscopes, such as the ones built by Robert Hooke (an English physicist) that let our eyes first see the microscopic. Just when humanity believes it has gotten hold of the principals which govern the natural world, it suddenly dawns on us that we actually know nothing. Indeed, looking at a slice of cork (see below) Hooke believed he saw small “cells” - the term we still use today. The initial discoveries of Hooke were followed up by the indefatigable Anton van Leeuwenhoek[5], who coming from a commercial background dedicated himself the development of more and more powerful instruments and communicated the results of his microscopic investigations he found to a wider audience. What Leeuwenhoek found was that there appeared to be ‘animalcules’ on most surfaces he analyzed, and indeed he was the first man to see bacteria with his own eyes. Strathern describes of Leeuwenhoek justly:

Leeuwenhoek’s very lack of scientific learning proved to his advantage. He simply described what he saw, with the minimum of speculation. Only the most basic of principles were applied to his observations. If a thing moved under its own propulsion, he judged it to be alive – no matter how minuscule or curious the object might be.

Leeuwenhoek’s “cells” seen in cork

Leeuwenhoek’s own words are quite amusing too:

… some animalcules were the most wretched creatures that I have ever seen; when they hit upon any particles of filaments they stuck entangled … and then pulled their body out into an oval, and did struggle, by strongly stretching themselves, to get their tail loose; whereby their whole body sprang back toward the pellet of the rail, and their tails then coiled up serpent-wise …

The discovering of animalcules and bacteria in general paved the way for the understanding that diseases ultimately derive from cellular activity, which forms the modern basis of modern biology and medicine. The effects on the public imagination were of course shocking, and not to be fully absorbed for quite some time. However, Swift was inspired enough to pen this gem:

So, naturalists observe, a flea

Has smaller fleas that on him prey;

And these have smaller still to bite ’em,

And so proceed ad infinitum

Just as parasitic activity will have some evolutionarily stable frequency in the gene pool, it seems that all medical discoveries inevitably lead to a new generation of medical quacks. If there was need for another line of evidence that there exists some common human psychology it is that people will pay for false hope and confirm their desires by seeing patterns where there are none. Strathern does a good job at presenting the various “alternative medicine” that became available with the decline in the belief of witchcraft and old wives remedies. The current nonsense-du-jour is that vaccines can lead to autism, so it was refreshing that Strathern provides a detailed summary of the life of Edward Jenner, the father of modern immunization.[6] His initial idea came from noticing that milkmaids seemed immune from getting smallpox. Indeed, we get the term vaccine from vacca meaning cow in Latin. Jenner’s publication of An Inquiry into the Cauess and Effects of Variolae Vaccinae was an instant success and Thomas Jefferson had vials of the vaccine shipped to America to have his family immunized (did that include Sally Hemmings I wonder?). But surely Jenner’s renown reached it pinnacle when Jenner wrote to Napoleon (who had the entire French army vaccinated) asking that two of his captured friends be released Napoleon declared “Ah, Jenner, je ne puis rien refuser a Jenner”.

In his book Strathern makes not that there is absence of one of the gender’s in the history of medicine, a sad fact that bespeaks the nature of sexism rather than women’s abilities, of course. Nevertheless, he does cover several important women in the history of medicine including Florence Nightingale and her rival (?) Mary Seascole in the development of nursing, Clara Barton (whose exceptional work during the American Civil War was purposely ignored), and exceedingly interesting Miranda Stewart who became a well-respected surgeon by pretending to be a man (something straight out of Shakespeare!).

One of the most discussed persons in Strathern’s book is Louis Pasteur, a man fascinating both for his intellectual discoveries (the germ theory of disease) and his ambitious nature. The book describes his personal agenda as such: “… Pasteur entered the fray with his own agenda, determined to protect the world against atheists, materialists, and Germans”. His first insight came from finding the solution to the spoiling of French wine during the process of fermentation. How come some batches went bad? Pasteur suspected (correctly) that if bacteria were able to get inside the casks they would feed off the fermenting sugars and eventually spoil the batch. He showed that heating the wine to a certain temperature would ensure that no bacteria could survive (i.e. pasteurization). In a series of now classic experiments, Pasteur showed that exposure to air could speed up fermentation, which he suspected contained bacteria. He should that different amounts of air exposure would lead to the spoiling of meat, proving that bacteria were also responsible for the putrefaction of food. His theory was subsequently applied to the French silk industry where he demonstrated that the only way to wipe out a certain disease was to kill the current generation of silk worms. A short summary demonstrates the shear magnitude of his life’s success: (i) proof that fermentation was driven by microbes (rather than merely chemistry), (ii) demonstrated the origin of microbes (rather than the current belief of ‘spontaneous generation’, (iii) showed that the role of microbes was the same in fermentation as in disease, (iv) demonstrated that microbe-induced disease could be cured by inoculation, and (v) applied this body of knowledge to treating rabies in humans.

The book continues with many other interesting characters in the history of medicine such as Paul Ehrlich (development of chemotherapy – treatment of infection by drugs), Sir Harold Gillies (founder of modern plastic surgery), and Alexander Fleming (discoverer of penicillin). While the book is written at a very general level and is a bit short on references and footnotes, it made for an enjoyable read and is a good introduction to the major persons and developments in the history of medicine. I would summarize this book as an introductory text that makes one want to go and acquire further information on many of the above subjects discussed.

Footnotes

-

I am merely paraphrasing his argument, see The Moral Landscape for a full elucidation of Harris’ ideas. ↩

-

Freude of course meaning joy in German and Kuhn for originator of the theory of paradigm shifts. ↩

-

Interestingly, history seems to show that doctors who discover any breakthrough are always rewarded with court positions presumably due to the belief by royalty that if anyone was aware of the elixir of life it was the person who found the most recent medical breakthrough. This of course still happens today and with different professions. Take economists, Nobel prize winners often find themselves as advisors to hedge funds (even if the track record of LTCM suggests this is perhaps not the best idea). Harvey himself was Charles I appointed “physitian extraordinary”. ↩

-

The four humors were: yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood (at least two of them exist!) with the corresponding elements of fire, earth, water, and air. ↩

-

Pronounced Lay-van-hook for the inquiring minds. ↩

-

Jenner also had other scientific interests and was the first to notice the cuckoo bird would deposit its egg in other birds nest and that young cuckoos would eject the other eggs out of the nest too (hence the male’s fear of being made a “cuckold” out of!). ↩