Gulliver's Travel by Jonathan Swift (Book Review)

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, or more commonly Gulliver’s Travels, is considered to be Swift’s best book,1 which was unsurprising to discover after finishing this great work. The book tells of four distinct journeys made by Lemuel Gulliver to fantastical lands inhabited by giants and miniature humans, flying islands, and an enlightened horse species known as the Houyhnhnms. The book is a delight to read as it mocks the pretensions of human nature by using other imaginary peoples as a mirror unto our own absurdities. Additionally Gulliver’s sycophantic reminisces about the foreign governments he encounters is a perfect parody of the travel literature at the time in which critical judgement is suspended for the host nation of the traveler.

Throughout the novel, Gulliver desperately wants to convince each of his host nations of the merits of his native England and enlightened Europe. Yet each time he fails to convince the people of the land he is staying in that he has any useful information for their local polity or insight into philosophical or scientific issues. Of course, being the expert satirists that he is, Swift uses these four imaginary lands as parodies on the cultural, religious, political, and scientific failings of European civilization. Like any great work of fiction, the book has aged extremely well, and is equally applicable to the deficiencies of the 21st century. Criticisms about human nature and politics tend to hold true throughout the ages as the latter is ultimately a reflection of the former.2

The First Journey: To Lilliput

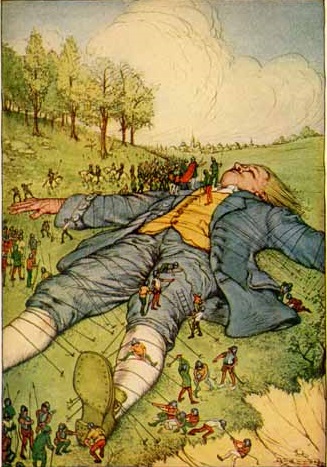

The character of Lemuel Gulliver is a surgeon by training who after years of sailing as a doctor on various ships, seeks to retire from the seas but is forced to return for pecuniary reasons. On voyage to the South Sea aboard the Antelope, the ship is rent asunder near Van Diemen’s Land (i.e. Tasmania), and Lemuel is luckily washed ashore on the island of Lilliput. Upon waking, Lemuel finds his arms and legs bounded to the ground and soon finds himself surrounded by miniature humans of about six inches in height. Already Mr. Gulliver displays his ingratiating tendencies by praising the design and exactitude of the constraints that were used to bind him to the ground:

These people are most excellent mathematicians, and arrived to a great perfection in mechanics, by the countenance and encouragement of the emperor, who is a renowned patron of learning.

Easily removing himself from the improvised fetters, he makes peace with the Lilliputians and agrees to return to their capital city of Mildendo in their confinement until an agreement can be reached as to his status within the kingdom. Another utterly charming feature of the Travels is the summary heading of each chapter. Consider Chapter V:

The author, by an extraordinary stratagem, prevents an invasion. A high title of honour is conferred upon him. Ambassadors arrive from the emperor of Blefuscu, and sue for peace. The empress’s apartment on fire by an accident; the author instrumental in saving the rest of the palace.

Despite explaining he is a normal-sized human from Europe, the emperor is skeptical to believe him and states:

For as to what we have heard you affirm, that there are other kingdoms and states in the world inhabited by human creatures as large as yourself, our philosophers are in much doubt, and would rather conjecture that you dropped from the moon, or one of the stars; because it is certain, that a hundred mortals of your bulk would in a short time destroy all the fruits and cattle of his majesty’s dominions: besides, our histories of six thousand moons make no mention of any other regions than the two great empires of Lilliput and Blefuscu. (bold mine)

As the Travels was published in 1726, the recent discoveries by Galileo and the unraveling of old scientific order must have been on Swift’s mind. The obstinacy of the emperor and his court philosophers to apprehend the visual evidence right in front of their eyes no doubt perfectly captures how dogma can blind men to their common sense. What’s further interesting about the emperor’s rational as to why Lemuel cannot actually come from a race of large men, is that he lists several reasons, consistent with what we know about psychological tendencies humans employ to reject views contrary to their desired belief:3

-

“Our explanation of this phenomenon should use existing narratives (dropping from the stars/moon) because these are concepts we are familiar with.” In other words, add another epicycle to the existing model rather than come up with a new one.

-

“The consequences of this belief lead to an outcome we would rather not have.” Of course this tells us nothing as to whether the idea is any less true or false!4

-

“This would represent a paradigm shift and therefore violate our existing authorities.”5

This is what excellent satire does. Mock a set of ways of being and seeing the world that is in contradiction to other values we simultaneously wish to hold such as logic or common sense. The emperor of Lilliput soon realizes that Lemuel’s strength would be well employed in subjugating the neighbouring kingdom of Blefuscu. White Mr. Gulliver refuses to enslave any free peoples (even if they’re only six inches in height) he does crush their naval armada and thereby lead to a forced armistice.

However, Lemuel begins to accumulate enemies in both the emperor’s cabinet as well as the Empress, who is mortified that he extinguished the palace fire by urinating on the flames. After being charged with treason, the most-learned emperor seeks only a token of justice to be sought.

That if his majesty, in consideration of your services, and pursuant to his own merciful disposition, would please to spare your life, and only give orders to put out both your eyes, he humbly conceived, that by this expedient justice might in some measure be satisfied, and all the world would applaud the lenity of the emperor, as well as the fair and generous proceedings of those who have the honour to be his counsellors. That the loss of your eyes would be no impediment to your bodily strength, by which you might still be useful to his majesty; that blindness is an addition to courage, by concealing dangers from us; that the fear you had for your eyes, was the greatest difficulty in bringing over the enemy’s fleet, and it would be sufficient for you to see by the eyes of the ministers, since the greatest princes do no more.

Unconvinced by his merciful sentencing, Gulliver flees to Blefuscu and there constructs a ship to return to his native country. Another continuing joke throughout the novel is Lemuel’s exceedingly poor qualities as a husband and a father as he is eminently bored by England, despite the paeans he gives it when abroad.

I stayed but two months with my wife and family, for my insatiable desire of seeing foreign countries, would suffer me to continue no longer.

The Second Journey: To Brobdingang

This time embarking for Surat, Lemuel finds on stranded Brobdingnag after his crew flees from an approaching giant whilst he is stranded watching his vessel disembark. Soon taken hostage by this giant which turns out to be just a very large farmer, a man of about twelve times Mr. Gulliver’s height. Lemuel is adopted by this seemingly generous family, as is taken care of with much tenderness by the farmer’s daughter Glumdalclitch. However, the farmer soon realizes that this miniature Brobdignagian would have great commercial value as a curio to be displayed and gawked at by the general public. Lemuel finds his new life as a travelling freak show highly dispiriting. Furthermore, as the animals and insects are also twelve times as large as they are in his land, he immediately finds himself slaying menacing rats during the beginning of captivity.

Gulliver eventually finds himself in the capital Lorbrulgrud where the royal family has become highly interested in this abnormal creature and request him as a cabinet curiosity. Swift imagines all the perils and challenges a small human would have in the court of a twelve-fold sized humans including: music played on instruments so loud they are almost deafening, wasps the size of large birds, and a jealous thirty-foot dwarf. In this sense, the book is proto-sci-fi. This second chapter suggests that Swift was sympathetic to issues to slavery and power imbalances in the contemporary society, highlighting that oftentimes the sense of superiority comes from physical power imbalances which tell nothing of any inherent intellectual rank order.

Concerned that the king’s “contempt he discovered towards Europe, and the rest of the world, did not seem answerable to those excellent qualities of mind that he was master of”, Lemuel describes to him the judiciousness of the British political system:

The House of Lords

[P]ersons of the noblest blood, and of the most ancient and ample patrimonies… these were the ornament and bulwark of the kingdom, worthy followers of their most renowned ancestors, whose honour had been the reward of their virtue, from which their posterity were never once known to degenerate.

The House if Commons

[P]rincipal gentlemen, freely picked and culled out by the people themselves, for their great abilities and love of their country, to represent the wisdom of the whole nation.

The Legal System

[J]udges, those venerable sages and interpreters of the law, presided, for determining the disputed rights and properties of men, as well as for the punishment of vice and protection of innocence.

The adulation Gulliver displays as of the second book will be amusingly contrasted in the fourth book when his encounter with the enlightened Houyhnhnms reveals to him the inferiority of the human species. However, even at the time the king of Brobdingnag is somewhat skeptical of this account and asks:

What qualifications were necessary in those who are to be created new lords: whether the humour of the prince, a sum of money to a court lady, or a design of strengthening a party opposite to the public interest, ever happened to be the motive in those advancements? What share of knowledge these lords had in the laws of their country, and how they came by it, so as to enable them to decide the properties of their fellow-subjects in the last resort? Whether they were always so free from avarice, partialities, or want, that a bribe, or some other sinister view, could have no place among them? Whether those holy lords I spoke of were always promoted to that rank upon account of their knowledge in religious matters, and the sanctity of their lives; had never been compliers with the times, while they were common priests; or slavish prostitute chaplains to some nobleman, whose opinions they continued servilely to follow, after they were admitted into that assembly?

Concluding:

My little friend … you have made a most admirable panegyric upon your country; you have clearly proved, that ignorance, idleness, and vice, are the proper ingredients for qualifying a legislator; that laws are best explained, interpreted, and applied, by those whose interest and abilities lie in perverting, confounding, and eluding them. I observe among you some lines of an institution, which, in its original, might have been tolerable, but these half erased, and the rest wholly blurred and blotted by corruptions. It does not appear, from all you have said, how any one perfection is required toward the procurement of any one station among you; much less, that men are ennobled on account of their virtue; that priests are advanced for their piety or learning; soldiers, for their conduct or valour; judges, for their integrity; senators, for the love of their country; or counsellors for their wisdom.

These long quotations only begin to do justice to Swift’s masterly exasperating writing style which brings such utter delight.

The Third Journey: Laputa the Flying Island and the Academy of Lagado

While waiting two months before setting off on the previous journey, Lemuel finds a new offer for adventure in less than ten days and once again leaves his family. After being attacked by pirates this time, he finds himself rescued by a flying island known as the Kingdom of Laputa. However, on this airborne fortress, only mathematics and music are considered valuable pursuits, leading to some awkward practical outcomes:

Their houses are very ill built, the walls bevil, without one right angle in any apartment; and this defect arises from the contempt they bear to practical geometry, which they despise as vulgar and mechanic; those instructions they give being too refined for the intellects of their workmen, which occasions perpetual mistakes. And although they are dexterous enough upon a piece of paper, in the management of the rule, the pencil, and the divider, yet in the common actions and behaviour of life, I have not seen a more clumsy, awkward, and unhandy people, nor so slow and perplexed in their conceptions upon all other subjects, except those of mathematics and music.

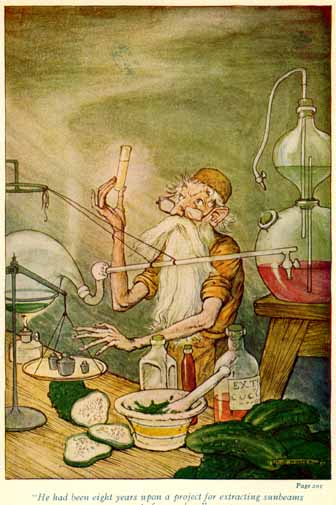

Additionally we find that flying island subjugates the kingdoms below by either “… keeping the island hovering over such a town, and the lands about it, whereby he can deprive them of the benefit of the sun and the rain, and consequently afflict the inhabitants with dearth and diseases…” or “… letting the island drop directly upon their heads, which makes a universal destruction both of houses and men.” Mr. Gulliver is invited to see the capital city of one of kingdoms Laputa rules, Lagado, where the scientific method has become a deranged pursuit of the nonsensical intellectual concoctions in the eponymous Academy:

[i] He has been eight years upon a project for extracting sunbeams out of cucumbers, which were to be put in phials hermetically sealed, and let out to warm the air in raw inclement summers.

[ii] His employment … was an operation to reduce human excrement to its original food, by separating the several parts, removing the tincture which it receives from the gall, making the odour exhale, and scumming off the saliva.

[iii] There was a most ingenious architect, who had contrived a new method for building houses, by beginning at the roof, and working downward to the foundation; which he justified to me, by the like practice of those two prudent insects, the bee and the spider.

[iv] We next went to the school of languages, where three professors sat in consultation upon improving that of their own country. The first project was, to shorten discourse, by cutting polysyllables into one, and leaving out verbs and participles, because, in reality, all things imaginable are but nouns. The other project was, a scheme for entirely abolishing all words whatsoever; and this was urged as a great advantage in point of health, as well as brevity. For it is plain, that every word we speak is, in some degree, a diminution of our lunge by corrosion, and, consequently, contributes to the shortening of our lives.

The whole description of the Academy of Lagado is clearly a parody of the Royal Society and university bureaucracies of Oxford/Cambridge at the time. While perhaps seeming anti-intellectual, in many ways it highlights the concern commonly expressed today as the critique of “scientism”, that is we need to separate the appearance of science (lab coats, microscopes, etc) with the practice of science (well-defined hypotheses, testable predictions, and reproducible experiments). It is an argument I am highly sympathetic to.

The Fourth Journey: The Land of Enlightened Horses

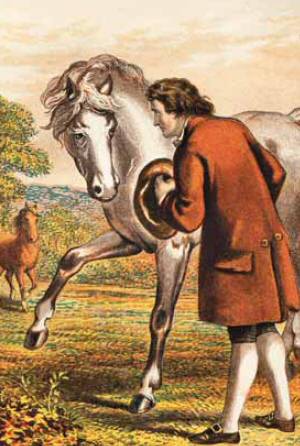

Upon his return, Gulliver this time stays at home for five months, but upon receiving a captaincy leaves “my poor wife big with child”. This time a mutiny forces Lemuel off the ship and his small boat reaches the Land of the Houyhnhnms where he initially meets a group of savage looking creatures called Yahoos.6 He initially fights one off for getting to close, but “they began to discharge their excrements on my head”, at which point a horse comes and chases the Yahoos off. After a second horse comes he notices what appears to be a dialogue between them conducted in neighing and hoof stamping. Astonished at their seeming intelligence, he follows them assuming that some human intelligence must be responsible for their training. However, after being let into their home he realizes that these horses, the Houyhnhnms, are their own enlightened species, and that the Yahoos are actually humans (the original Morlocks!), which have degenerated from the use of speech.

As time goes by, Lemuel learns to speak to the Houyhnhnms and become enamored by their way of living as these noble creatures display none of the vices of men. Indeed, he struggles at length to explain corruption, lying, wars, etc, to the morally unimpeachable horses. The whole chapter is worth reading multiple times, and once again I will cite the most amusing expatiations (note the comparison to the descriptions in the second voyage):

Casus Belli

He asked me, “what were the usual causes or motives that made one country go to war with another?” I answered “they were innumerable; but I should only mention a few of the chief… Difference in opinions has cost many millions of lives: for instance, whether flesh be bread, or bread be flesh; whether the juice of a certain berry be blood or wine; whether whistling be a vice or a virtue; whether it be better to kiss a post, or throw it into the fire; what is the best colour for a coat, whether black, white, red, or gray; and whether it should be long or short, narrow or wide, dirty or clean; with many more. Neither are any wars so furious and bloody, or of so long a continuance, as those occasioned by difference in opinion, especially if it be in things indifferent.

Lawyers and the Legal System

I said, “there was a society of men among us, bred up from their youth in the art of proving, by words multiplied for the purpose, that white is black, and black is white, according as they are paid. To this society all the rest of the people are slaves. For example, if my neighbour has a mind to my cow, he has a lawyer to prove that he ought to have my cow from me. I must then hire another to defend my right, it being against all rules of law that any man should be allowed to speak for himself. Now, in this case, I, who am the right owner, lie under two great disadvantages: first, my lawyer, being practised almost from his cradle in defending falsehood, is quite out of his element when he would be an advocate for justice, which is an unnatural office he always attempts with great awkwardness, if not with ill-will. The second disadvantage is, that my lawyer must proceed with great caution, or else he will be reprimanded by the judges, and abhorred by his brethren, as one that would lessen the practice of the law. And therefore I have but two methods to preserve my cow. The first is, to gain over my adversary’s lawyer with a double fee, who will then betray his client by insinuating that he hath justice on his side. The second way is for my lawyer to make my cause appear as unjust as he can, by allowing the cow to belong to my adversary: and this, if it be skilfully done, will certainly bespeak the favour of the bench. Now your honour is to know, that these judges are persons appointed to decide all controversies of property, as well as for the trial of criminals, and picked out from the most dexterous lawyers, who are grown old or lazy; and having been biassed all their lives against truth and equity, lie under such a fatal necessity of favouring fraud, perjury, and oppression, that I have known some of them refuse a large bribe from the side where justice lay, rather than injure the faculty, by doing any thing unbecoming their nature or their office.

It is a maxim among these lawyers that whatever has been done before, may legally be done again: and therefore they take special care to record all the decisions formerly made against common justice, and the general reason of mankind. These, under the name of precedents, they produce as authorities to justify the most iniquitous opinions; and the judges never fail of directing accordingly. In pleading, they studiously avoid entering into the merits of the cause; but are loud, violent, and tedious, in dwelling upon all circumstances which are not to the purpose. For instance, in the case already mentioned; they never desire to know what claim or title my adversary has to my cow; but whether the said cow were red or black; her horns long or short; whether the field I graze her in be round or square; whether she was milked at home or abroad; what diseases she is subject to, and the like; after which they consult precedents, adjourn the cause from time to time, and in ten, twenty, or thirty years, come to an issue. It is likewise to be observed, that this society has a peculiar cant and jargon of their own, that no other mortal can understand, and wherein all their laws are written, which they take special care to multiply; whereby they have wholly confounded the very essence of truth and falsehood, of right and wrong; so that it will take thirty years to decide, whether the field left me by my ancestors for six generations belongs to me, or to a stranger three hundred miles off. In the trial of persons accused for crimes against the state, the method is much more short and commendable: the judge first sends to sound the disposition of those in power, after which he can easily hang or save a criminal, strictly preserving all due forms of law.

Prime Ministers

[F]irst or chief minister of state, who was the person I intended to describe, was the creature wholly exempt from joy and grief, love and hatred, pity and anger; at least, makes use of no other passions, but a violent desire of wealth, power, and titles; that he applies his words to all uses, except to the indication of his mind; that he never tells a truth but with an intent that you should take it for a lie; nor a lie, but with a design that you should take it for a truth; that those he speaks worst of behind their backs are in the surest way of preferment; and whenever he begins to praise you to others, or to yourself, you are from that day forlorn. The worst mark you can receive is a promise, especially when it is confirmed with an oath; after which, every wise man retires, and gives over all hopes. There are three methods, by which a man may rise to be chief minister. The first is, by knowing how, with prudence, to dispose of a wife, a daughter, or a sister; the second, by betraying or undermining his predecessor; and the third is, by a furious zeal, in public assemblies, against the corruption’s of the court. But a wise prince would rather choose to employ those who practise the last of these methods; because such zealots prove always the most obsequious and subservient to the will and passions of their master. That these ministers, having all employments at their disposal, preserve themselves in power, by bribing the majority of a senate or great council; and at last, by an expedient, called an act of indemnity” (whereof I described the nature to him), “they secure themselves from after-reckonings, and retire from the public laden with the spoils of the nation.

Public Health

I told him “we fed on a thousand things which operated contrary to each other; that we ate when we were not hungry, and drank without the provocation of thirst; that we sat whole nights drinking strong liquors, without eating a bit, which disposed us to sloth, inflamed our bodies, and precipitated or prevented digestion; that prostitute female Yahoos acquired a certain malady, which bred rottenness in the bones of those who fell into their embraces; that this, and many other diseases, were propagated from father to son; so that great numbers came into the world with complicated maladies upon them; that it would be endless to give him a catalogue of all diseases incident to human bodies, for they would not be fewer than five or six hundred, spread over every limb and joint—in short, every part, external and intestine, having diseases appropriated to itself…

Doctors

… To remedy which, there was a sort of people bred up among us in the profession, or pretence, of curing the sick. And because I had some skill in the faculty, I would, in gratitude to his honour, let him know the whole mystery and method by which they proceed. Their fundamental is, that all diseases arise from repletion; whence they conclude, that a great evacuation of the body is necessary, either through the natural passage or upwards at the mouth. Their next business is from herbs, minerals, gums, oils, shells, salts, juices, sea-weed, excrements, barks of trees, serpents, toads, frogs, spiders, dead men’s flesh and bones, birds, beasts, and fishes, to form a composition, for smell and taste, the most abominable, nauseous, and detestable, they can possibly contrive, which the stomach immediately rejects with loathing, and this they call a vomit; or else, from the same store-house, with some other poisonous additions, they command us to take in at the orifice above or below (just as the physician then happens to be disposed) a medicine equally annoying and disgustful to the bowels; which, relaxing the belly, drives down all before it; and this they call a purge, or a clyster. For nature (as the physicians allege) having intended the superior anterior orifice only for the intromission of solids and liquids, and the inferior posterior for ejection, these artists ingeniously considering that in all diseases nature is forced out of her seat, therefore, to replace her in it, the body must be treated in a manner directly contrary, by interchanging the use of each orifice; forcing solids and liquids in at the anus, and making evacuations at the mouth.

Shrinks and Quacks

But, besides real diseases, we are subject to many that are only imaginary, for which the physicians have invented imaginary cures; these have their several names, and so have the drugs that are proper for them; and with these our female Yahoos are always infested. One great excellency in this tribe, is their skill at prognostics, wherein they seldom fail; their predictions in real diseases, when they rise to any degree of malignity, generally portending death, which is always in their power, when recovery is not: and therefore, upon any unexpected signs of amendment, after they have pronounced their sentence, rather than be accused as false prophets, they know how to approve their sagacity to the world, by a seasonable dose. They are likewise of special use to husbands and wives who are grown weary of their mates; to eldest sons, to great ministers of state, and often to princes.

Conclusion

The Travels is a masterful book that will require re-reading throughout ones life to remind oneself that in the farcical procession of the human display has always been so since time immemorial. Whilst Lemuel seeks nothing more than to live amongst his enlightened horse masters, their Assembly decides to banish him lest he organize the current lot of Yahoos into brigands. Distraught, Gulliver constructs a craft and is picked up by a Portuguese captain where he returns a somewhat bitter man to his native land disgusted by the perception of humans as as little more than hairless Yahoos.

At the same time, his new-found cynicism makes him not the least “provoked at the sight of a lawyer, a pickpocket, a colonel, a fool, a lord, a gamester, a politician, a whoremonger, a physician, an evidence, a suborner, an attorney, a traitor, or the like”. And he eventually reconciles the presence of his family of Yahoos, albeit with certain precautions asking them to “… sit at dinner with me, at the farthest end of a long table; and to answer (but with the utmost brevity) the few questions I ask…” Nevertheless, Lemuel’s philosophy remains forever wedded to the enlightened equine empire of reason he once glimpsed:

But the Houyhnhnms, who live under the government of reason, are no more proud of the good qualities they possess, than I should be for not wanting a leg or an arm; which no man in his wits would boast of, although he must be miserable without them. I dwell the longer upon this subject from the desire I have to make the society of an English Yahoo by any means not insupportable; and therefore I here entreat those who have any tincture of this absurd vice, that they will not presume to come in my sight.

Footnotes

-

Swift was also known for his essays such as a A Modest Proposal, as well as his poetry. Although the poetry is not as well known, and he is not found in my copy of Oscar William’s Immortal Poems of the English Language. ↩

-

I remember an interesting analogy I once heard (although I cannot remember from where) which went something like this: imagine trying to explain to a bronze age peasant living in Palestine three modern events: the mapping of the human genome, the Syrian civil war, and the UK parliamentary expense scandal. I think most would agree that the first would effectively be impossible as the concepts that underpin its understanding (cell biology, biochemistry, computation, etc) are a bridge too far for an ancient mind to appreciate. However, war and corruption would be quickly understood. ↩

-

I mean this is the general sense: self-rationalization is something we all do. ↩

-

To use a very contemporary example of this, many left-of-center and/or persons with higher education think that merely because Donald Trump would be a bad president this is somehow a reason as to why he will not be elected. To have to down in writing four months before the election, I think Trump winning is currently the most likely outcome. ↩

-

Modern parallels of this can be seen in academic research whereby findings which make clash with existing research tend not to be published or alternative specifications which lead to statistically insignificant results are left out of papers. ↩

-

The word yahoo as an uncivilized hooligan comes from the Travels. ↩