Genome by Matt Ridley (Book Review)

I knew I would not be disappointed with Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters as I had read Ridley’s previous book The Red Queen, about the biological origins of sexual reproduction with great delight. Ridley is a well-respected journalist with The Economist, and knows how to write authoritatively on issues of popular science.[1] His specific knowledge of genetics and biology has helped him hone in on the key principals that one need appreciate to understand the central dogma behind modern biology and genetics. Do to its abstract nature, the field of genetics is prone to analogies, many of them confounding, but Ridley does a good job at finding appropriate comparisons and articulating how satisfactory the concurrence is between these conceptual shorthands and underlying reality.

The book is broken into twenty-three chapters corresponding to a given chromosome,[2] and each chapter highlights a specific gene native to that chromosome. The chapter titles range from conflict to intelligence, highlighting that the genetic landscape has a nebulous and important impact on our lives. A firm believer of the simultaneous forces of nature and nurture, Ridley has little patience for behaviorists, and stresses that genetic effects from physiology to psychology are pervasive but also complex. He likens the relationship between the limits of human choice and genes to the development of a picture: different hues can applied, the contrast can be adjusted, but regardless of the photographic developer, the image will not come out as a monkey (with human DNA that is).

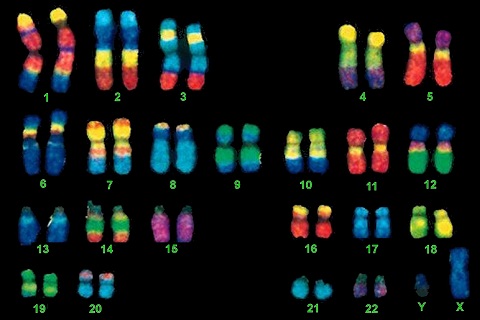

Our chromosomes in full glory

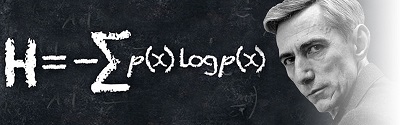

In Chapter 1, Life, Ridley provides a high level overview of the relationship between genetic information and lifeforms. As biology must have begun with some form of self-replication, the relationship between life and heredity (the link between the parent and progeny) is inseparable: $\text{biology} \leftrightarrow \text{self-replication}$. From the perspective of information theory à la Shannon, biological forms are just information. In statistical mechanics entropy measures the amount of “hidden information” contained in the position of particles (think the placement of gas particles in a room). Specifically, the link between entropy in thermodynamics and information theory is the (minimum) number of yes/no questions one would need to ask in order to determine the position of every particle in a system. In binary code there is one bit stored in each discrete position of code, as there are $log_{2}M$ bits of information in a digital code where $M$ is the number of symbols in the code. Hence, DNA stores two bits of information per nucleotide.[3] As information is the reciprocal of entropy, biological forms are a way of formatting a collection of random particles into a well-ordered machine. The concepts that underlie computer science are inseparable from the natural world.[4]

Claude Shannon's information theory has a surprising connection to biology

Upon reflection, it turns out I take almost everything I read about the world on the word of others. When I see read a news article about the use of CRISPR gene editing technology to fight against microbial resistance, I take it on (good) faith that the journalist who wrote the article has not fabricated the story out of whole cloth and that the scientists who published the research have not been fibbing about the phenomenon they observe on the molecular-level. Of course I have good reason to believe that their incentive is to be honest, but one should always remember that any information one hears has a measure of hearsay. And so it was with the number of human chromosomes, which were confidently estimated at twenty-four until 1955. The discovery that we had been over-counting our chromosome count by 4.4% told us something important about our evolutionary history: we had “lost” a chromosome since our last common ancestor with the chimps.[5] And yet, even after the merger and acquisition of one of our chromosomes, we still share 98% of our DNA with chimpanzees. To clarify the word “share”, this just means that 98% of our genes line up, but that the specific details on a nucleotide basis differ. Specifically, I “share” 100% of my DNA with you, however on a nucleotide-per-nucleotide comparison we are of course different because I have different alleles (variants of genes). In case you were wondering what the Vatican’s views are on this whole “evolution thing”, it turns out that back in 1950, Pope Pious XII said that it was probably okay:

For these reasons the Teaching Authority of the Church does not forbid that, in conformity with the present state of human sciences and sacred theology, research and discussions, on the part of men experienced in both fields, take place with regard to the doctrine of evolution, in as far as it inquires into the origin of the human body as coming from pre-existent and living matter - for the Catholic faith obliges us to hold that souls are immediately created by God.

In 1996, Pope John Paul II added the theological flourish of ontological discontinuity.

With man, we find ourselves facing a different ontological order—an ontological leap, we could say. But in posing such a great ontological discontinuity, are we not breaking up the physical continuity which seems to be the main line of research about evolution in the fields of physics and chemistry? An appreciation for the different methods used in different fields of scholarship allows us to bring together two points of view which at first might seem irreconcilable. The sciences of observation describe and measure, with ever greater precision, the many manifestations of life, and write them down along the time-line. The moment of passage into the spiritual realm is not something that can be observed in this way—although we can nevertheless discern, through experimental research, a series of very valuable signs of what is specifically human life. But the experience of metaphysical knowledge, of self-consciousness and self-awareness, of moral conscience, of liberty, or of aesthetic and religious experience—these must be analyzed through philosophical reflection, while theology seeks to clarify the ultimate meaning of the Creator’s designs.

Did you catch the ontological enjambment? As long as the soul snuck its way into mitochondrial Eve, things are doctrinally kosher.

One of the best chapters of the book is Conflict, which looks at the sex chromosome, and the battle of the sexes that it has generated. In evolution, interlocus contest evolution (ICE) occurs whenever a gene in species A interacts with a gene in species B. In a subset of cases, A can be equal to be B, and the genetic contest can occur within the genome of a given species.[6] Intersexual conflict is a perfect example of a subset of ICE, whereby the evolutionary interests of multiple genes can differ, even within the same chromosome! Just as individual Hollywood actors want to increase their lines at the expense of other actors, so too do genes. While the genes that direct the creation of a male/female human are found within the human genome, they nevertheless can develop antagonistic alleles.

Abalone mollusks: a typical sexual preditor

Examples abound in nature. Consider abalone moluscks whose sperm contain a protein which it requires to bore through the outer membrane which which encases the female egg. How “strong” should this protein be? From the male’s perspective, the stronger the better as a sperm that can bore quickly has a higher chance of winning the fertilization race. Yet the females would disagree as they would prefer slow borrowing sperm so their immune system and muscular repair can reduce the chance of infection from an “entry wound”. Evidence suggests that the potency of the male abalone sperm and the fortification of the female egg have been increasing overtime due to an evolutionary drive stemming from this example of intersexual conflict.

Three way races can also occur, because again, the fundamental unit of evolutionary selection is the gene. In mating, males have an incentive to reduce the female remating rate and to increase her short-run fecundity. Examples of this include mate guarding and, at a chemical level, proteins in sperm which reducing the female’s sexual appetite (this occurs in fruit flies). Females instead care about their long-run fecundity, and want to invest equal resources into their children. Yet the male interest is not uniform with males that have just mated and those that are trying to elicit a second round of copulation. In the later case, the develop of semen displacement adaptions increases fitness for second-round mating cycles. The shape of the human penis may be such an adaption.

A tale of two tails

The battle of the sexes also shows up in courtship, which is defined by any communication/signal between the male and female which affects the probability of mating. The theory of interlocus contest evolution would hypothesize that males have an evolutionary incentive to develop courtship signals that increase the promiscuity of females whilst females will evolve counter measures. Consider two genera of poecilid fish, the Priapella and the Xiphophorus, with the latter having developed an elongated tail that enhances their success of courtship. Interestingly, Priapella females also prefer males with longer tails (when presented with males of the other genera), even though there own males lack such ornamentation. This implies that the preference for long tails is a pleiotropic (incidental) outcome of the psychology. If intersexual conflict is occurring, and the ICE-hypothesis holds, then we should expect to see females of the Xiphophorus species having developed some amount of “resistance” to the length of the male’s tail. Observational evidence confirms that this is indeed the case, and the Priapella females are much more smitten by the gaudy displays of the other males tales. Allow me to coin this as the Desdemona effect.

Evolution gone horribly wrong

Why are babies so noisy? Blame interlocus contest evolution. Consider babies crying out for food or milk. Parents value a signal of how hungry their children are so that they can feed them appropriately (and safeguard their genes of course). Children also value a signal that they can use to mediate their dietary requirements. So will children cry at a rate which expresses their true hunger (the hidden information) or will they have incentive to cry “too much”, and if so why? Let’s imagine the following signalling game.

Suppose offspring are either hungry ($H$) or not hungry ($L$), and that hungry children need $y_H$ calories and not hungry children need a smaller $y_L$ number of calories. Next suppose that children can be in a binary state of crying ($e=1$) or not-crying ($e=0$). Suppose crying is a legitimate signal because that cost of crying in calories ($c_{i \in \{H,L\}}$) is a function of the state of hunger, such that $c_L > c_H$, which intuitively means that it’s less physiologically costly for a hungry child to cry than a child who is not hungry.[7] A stable equilibrium will occur where hungry children cry and not hungry children don’t cry when:

\[\begin{align} y_H - c_H > y_L > y_H - c_L \hspace{4pt} \label{eq:cry} \end{align}\]Equation \eqref{eq:cry} is quite intuitive: the first inequality says that there’s a higher net return from crying and being hungry than not crying and not being hungry. In other words, if you’re truly hungry, it still pays to cry and receive the larger caloric supplement than not crying and receiving the smaller caloric intake. The second part of the inequality states that the net benefit of crying when you’re not hungry and receiving a larger caloric intake is smaller than not crying and receiving the smaller caloric intake when you’re not hungry. In other words, crying is just too costly when you’re not hungry, and the cost of doing so outweighs the benefit of the higher caloric intake. This is a stable equilibrium because a parent knows that their offspring will cry when they are type $H$ and not cry when they are type $L$.

Is the end of the story? In evolutionary terms, no. Genes which reduce the cost of crying will increase in frequency, until one of the inequalities is broken. At this point, the cost of a not hungry child crying and getting a larger meal share is feasible, and the existing rule system (crying gets larger meal share) no longer works. At this point, parents may begin to base feeding decisions based on some threshold of the intensity of crying to discern whether their offspring are truly hungry. However, the intensity of infants’ crying will continue to escalate, and parents will continue to demand a higher threshold due to this arms race. What’s important to remember is that this evolutionary arms race is not occurring between cheetah and gazelle running speed genes, but on the human genome itself! Genes are selfish.

While genes code for proteins, most of the human genome is not actually made of such protein-encoding genes (only around 1.5% of the human genome). The rest is made up of: “genes for noncoding RNA (e.g. tRNA and rRNA), pseudogenes, introns, untranslated regions of mRNA, regulatory DNA sequences, repetitive DNA sequences, and sequences related to mobile genetic elements”. Transposable elements are genetic sequences which are able to cut and paste themselves onto different parts of the human genome. What is the value of many of these sequences? The answer is none, from the anthropocentric perspective that is. Millions of years ago retroviruses inserted their viral DNA into our mammalian ancestor’s genome and it has been floating around ever since. In addition to imposing a molecular burden of longer-than-necessary DNA, these human endogenous retrovirus sequences also offer a more accommodating integration platform for retroviruses like AIDS. As Ridley puts it:

If you think being descended from apes is bad for your self-esteem, then get used to the idea that you are also descended from viruses.

I wonder what Tennyson would have said if he had been told this?

No more? A monster then, a dream,

A discord. Dragons of the prime,

That tare each other in their slime,

Were mellow music match’d with him.

One other interesting theory à la intragenomic conflict is whether or not homosexuality, which is widespread in the animal kingdom, could be the result of a hormone on the X chromosome which improves some aspect of female reproductive fitness at the expense of males. It has been noted that homosexuality in humans is inheritable, and tends to occur on the maternal side of the family tree. In a population of equal numbers of men and women, two-thirds of X-chromosomes reside in females. Consequently, if, and this is purely a hypothetical example, an X-chromosome gene enhances female attractiveness but simultaneously increases the rate of male homosexuality, this gene will continue to be selected for as long as the decrease in male reproductive fitness is less than female reproductive fitness, in toto. Although this example may actually be what is happening.

Mothers and aunts on the maternal line of homosexuals had around one-fifth to one-fourth more kids than the heterosexual comparison, and also than the paternal line.

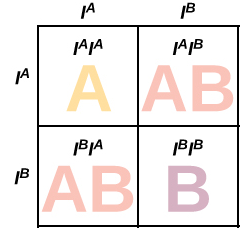

When the human genome was declared complete in 2003, one may have been forgiven for asking question, which human was the human genome sequenced from? Does it even make sense to say there is a single human genome given the staggering genetic diversity that exists? The Humane Genome Project used a collection of several individuals, although “[m]uch of the sequence (>70%) of the reference genome produced by the public HGP came from a single anonymous male donor from Buffalo, New York (code name RP11).” Could we imagine a “representative” genome, in the same way that we can think of a representative Canadian (average height, weight, income, life expectancy, etc)? The answer is no, because there are some aspects of our genome which have no stable equilibrium: their dynamics will perpetually remain in flux. Blood type is an excellent example of this. People that are blood type A (they have two A blood-type genes) have superior resistance to cholera than individuals with blood-type B. So why doesn’t the gene which encodes for blood type B die out? It turns out individuals with blood type AB have an even better resistance to disease. However, a couple with the “best” blood type (AB) will produce 25% of their offspring with blood type AA. In other words:

The very combination that is most beneficial in your generation guarantees you some susceptible children.

Never ending genetic diversity of blood types

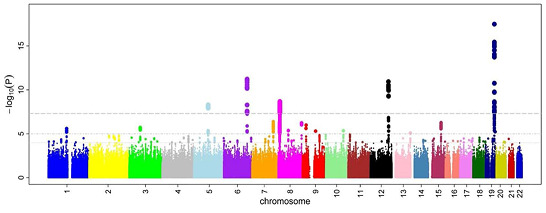

In Obama’s 2015 State of the Union speech, he announced the creation of the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI), which is aiming to sequence the full genomes of one-million Americans. This initiative will have obvious synergies with the NIH’s National Cancer institute’s PMI program. This huge data set will be sufficiently large to power many genome wide association studies.

Genome wide association studies will be powered by initiatives such as the NIH's PMI

As previous examples have shown, an understanding of our genetic history can be humbling. Humans tend to be taken aback when they find out that something unique in their physiology or psychology has a simulacrum in the animal kingdom. This initial instinct can be easily suppressed when one contemplates how cool it is that everything we see in biology operates on the same software and hardware. For example Hox genes are extremely important genes for embryological development in almost all animal species. In what can only be described as jaw-dropping, several genes in fruit flies can be replace by their human counterparts and develop normally! Even though we shared a common ancestor with Drosophila more than 700 million years ago, this embryological subroutine remains largely unchanged.

Before the human genome was sequenced, scientists had expected to find around 80-100K genes, whereas they instead found between 20-30K. Why was the estimate off by a factor of four? Partly we may have underestimated the combinatorial value of genes,[8] but more importantly we did not understand that the transcriptional potential of a cell can be affected by external or environmental factors. The study of these factors is known as epigenetics.

Using the well-rehearsed analogy of DNA to language: nucleotides are letters, codons are words, genes are paragraphs, chromosomes are chapters, and the genome is the book. Additionally, our book of life gets notes added in the column margins or yellow highlights. These ‘highlights’ on DNA are known as epigenetic tags and they affect how a gene gets expressed. We have long known that the expression of genes is governed by protein-binding regions, whereby in the presence of a surfeit of specific chemicals, certain regions of the genome will shut down. This was discovered in the 1960s by Monod and Jacob, whereby E. coli is able to switch from producing enzymes that digest either lactose or glucose, depending on the availability of either energy source. Epigenetic tags such as methyl groups are attached to specific regions of DNA and help to inhibit gene functions. This allows for the creation of differentiated cell types: skin cells than form our skin and brain cells that become a network neurons.[9]

The rest of the book is filled with vignettes about other interesting genes. A focus of many chapters is on genetic etiology, because so often news stories are driven by: “a gene found for disease X”. Of course, as Ridley points out, when we say that BCRA1 leads to breast cancer, we actually mean that people who do not have a proper version of this gene are more likely to get the disease. It would be like saying: liver organ found to cause cirrhosis or stomach organ found to cause ulcers. While any book about genetics is at risk of being dated due to the rapid progress being made in this field, Ridley’s clear prose and insight easily extends the shelf life of his writing to the present day.

Footnotes

-

It has always been my view that journalists write the best popularization books. ↩

-

Recall dear reader that we humans are genetically diploid (two matching pairs of chromosomes - male sex chromosome aside), and have twenty-two autosomal chromosomes plus one pair of sex chromosomes. Our total chromosome count is one less than our apish cousins, but nine more than a Tasmanian devil. Keep in mind that ones chromosome count tells one nothing about the sophistication of a species: barley has fourteen chromosomes but oats have fourty-two, for example. ↩

-

Alternatively one could think of each letter of DNA being coded by two one-bit binary codes: (00), (01), (10), and (11). ↩

-

While the specific details of biological life are extremely parochial to earth (the use of nucleotides and amino acids), that life is powered using digital information may have been inevitable as there is only one way to do a calculation. ↩

-

Recall we are not descended from monkeys, but rather shared a common ancestor with them. ↩

-

For a thorough review of the subject see the article The Enemies within: Intergenomic Conflict, Interlocus Contest Evolution (ICE), and the Intraspecific Red Queen by Rice and Holland (1997). ↩

-

I happen to be using calories as the unit of cost/benefit, but one could use an even more general “survival points” or “evolutionary fitness score”, etc. ↩

-

For example the average speaker knows 20-35K English words, and yet we can produce an infinite variety of works. ↩

-

Recall that each cell in our body (basically) has the same DNA sequence, but not the same epigenetic tags. ↩