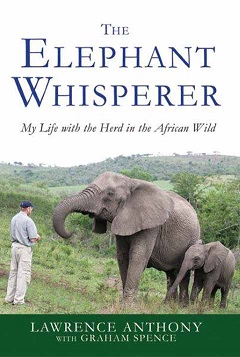

The Elephant Whisperer by Lawrence Anthony (Book Review)

The Elephant Whisperer by Lawrence Anthony is not the sort of book I would normally pick up. In fact I cannot remember the last time I got a book from the “Animals/Pets” section of any bookstore. However, one of the advantages of participating in a book club is that one inevitably reads books that would be beyond the gamut of one’s perceived literary interests. My expectations were low; I had expected a somewhat wishy-washy exploration of the emotional relationship between a African naturalist and a group of elephants. Instead, I found myself absorbed in Lawrence Anthony’s exciting story of setting up one of the largest private eco-reserves in Africa and integrating a herd of unruly elephants into his demesne.

Lawrence Anthony was born in 1950s south Africa, and has lived in Rhodesia, Malawi, and and Zambia before settling in South Africa. Hence he grew up in a time when the political power of the white-settler communities of Africa were being displaced by black-majority governments. To his credit, he was an opponent of apartheid during his life and has completely integrated himself in the the local Zulu culture, language, and tribal customs.[1]

After apartheid ended in 1994, Lawrence bought the Thula Thula game reserve with help from his partner (wife) Francois,[2] and they committed to changing it from a hunting ground to an eco-reserve. When the Elephant Managers and Owners Association called Anthony to let him know that a nearby reserve planned on killing their herd of elephants because of aggressive behavior and break out attempts, he volunteered to take them in.

As someone who is not familiar with wildlife management, this offer entailed an enormous level of responsibility and care which I would not have expected. First, the elephants had to be kept in a boma, a sort of large electrified holding cage in order to acclimatize the animals to their new area as well as to teach them to treat fences as objects to avoid. However the elephants were able to use their strength to knock over a tree which disabled the electrical system and made a dash for it. This level of inductive reasoning coming from a herd of animals was amazing. It required deducing the effects of several physical events and consequences: pushing over tree -> falling tree in this direction -> weakens fence -> break through fence.

Luckily Lawrence was able to get them back in after their break out by hiring a local helicopter pilot to dive bomb the herd and shepherd them back to the holding pen. On the Thula Thula reserve firearms are only used in the most dire situations, and since these elephants had already seen some of their family members shot, no guns were used to scare them towards the direction of the boma encampment – a very humane choice. In the subsequent months Lawrence made a herculean effort at befriending the elephants by standing by the fence everyday until they became used to presence. He credits the strength of his friendship with the herd to his use of speaking to them directly (in English), although I am sure it was the body language and tone he used that made the important difference (as in he could have been saying gibberish in Latin to the same effect).

Eventually the elephants were ready to be integrated into the large reserve. However the challenges did not end there. Thula Thula had enemies from both within and outside the reserve. Corruption is endemic throughout South Africa, including in the staff that Lawrence employs. In the first instance, Lawrence and David (his most trusted officer and a fellow white South African) had to break up an antelope poaching ring that was being carried out by the security guards, the Ovambos, who were former soldiers from Namibia. They had to build up sufficient evidence and then bring in the South African police the carry out wide scale arrests. While it all went smoothly, I can easily imagine it ending with a shoot out, all of which highlights the dire security situation in South Africa. We also are given two instances where Lawrence, David, and some of his other (non-corrupt) security staff chase down poaches and have to shoot (non-fatally) some of them. Firefights are not what I expect on an animal sanctuary, but in a desperately poor region with a chance to make significant money from meat or ivory it may be inevitable. Lawrence also has to meet with a tribal leader who wants (from cattle-ranching reasons) to have him killed and he is able to use his sheer force of presence to intimidate his opponent into submission.

Throughout the book one gets the sense that Lawrence loves his lifestyle and wouldn’t want to be doing anything else. He makes several references to having a “good but tough life”. He likes that human interactions are more honest and transparent out on the veldt. I am not totally sure what to make of his wife Francois Malby, who appears to be a Parisian out of her urban comfort zone. Her garden is destroyed by the wildlife and her picnics ransacked by monkeys. She has a French poodle and does appear to go out on the reserve that often. She and Lawrence seem to be quite culturally different and I found his jocular humor towards his wife’s missteps in the bush to be somewhat ungallant. Although he is extremely loyal towards her and no doubt loves her inimitably.

One other criticism I have is for Anthony’s belief in spiritualism. On the one hand he points out the various juju beliefs that the locals have and how this can lead to socially pathological outcomes such as burning down the houses of “witches”. Yet at the same time, Lawrence seems guilty of over-interpreting his interactions with the elephants into the realm of the mystical. He suggests that the elephants can “sense” his presence, such as being to tell when his flight has been delayed in an airport hundreds of miles away. In my view this is no service to those interested in animal rights, as he reduces the stunning displays of intellectual and emotional intelligence by the animals to mere mysticism. Animals like elephants deserve near-human rights due to their level of conscious experience being very close to ours. However, by giving them “souls” that communicate with extrasensory perception he is at risk of reducing the validity of underlying ethical rights of animals to far less sustainable claims of spiritual consonance. However, this is just a small complaint with the book.[3]

This was a page-turner for a non-fiction book and I am now interested in reading Lawrence Anthony’s other books about his rescue of animals from the Baghdad zoo (Babylon’s Ark) during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the saving of white rhinoceroses from southern Sudan (The Last Rhinos). He clearly lived an exciting life and displayed the hard-nosed realism that is needed to protect animals in dangerous countries. Reading books about animals is also a good reminder that the ethical obligations we have towards humans deserve to be applied, at least in some diminutive form, to the animal kingdom. Just as meditating on the grand and unfathomable scale of the observable universe can be cathartic for humans, feeling empathy towards other animals with a similar level of emotional development can help us to step outside of our cloistered anthropocentric perspective.

Footnotes

-

While race is an issue which is present in all social interactions in South Africa, one does not sense a strict divide between the white/black community in this area, although this may speak to the fact that there appear to be very few white individuals near the Thula Thula reserve. Aside from Lawrence and his wife, plus several of their staff, there does not appear to be a white community. ↩

-

At least this is how I understand it from reading the book. My interpretation was that they met in London, and he convinced her to come back to South Africa with him to buy the reserve together. ↩

-

The reason why all spiritual are supernatural claims are unconvincing is that they are noticed in real-time rather than being predicted. For example, if I walk into a “haunted” house and react to every time a window slams shut I am most certainly going to be attributing the presence of ghosts to gusts of wind. If instead I were to predict that the ghost always slams the windows at 8:13pm, and this happens without the least trace of wind, now we’re having an interesting conversation because a purported knowledge of supernatural forces is actually mapping onto to physical phenomenon before it actually happens. Let us return to the case of the elephants. If Lawrence were to record the position of the elephants every time he were flying back to the reserve and found that for every instance in which the flight was delayed due to forces beyond his control the herd avoided going to his house, but whenever the plane was on schedule they did walk towards his house, then we are having an interesting conversation. If on the other hand, sometimes the elephants walk towards the house and sometimes they do not, but they only notice the times this coincided with Lawrence returning home then a false pattern would be garnered by taking account of only those observations which fit a certain hypothesis. This is why supernatural phenomenon never show up in the science laboratory, because the pattern recognition systems we use on a day-to-day basis leave us vulnerable to attribute random phenomenon to spiritual forces. And such random patterns and always found to be just that in a controlled experiment, random. Apophenia (the tendency to see patterns in random data) and observation bias are well documented human tendencies that make clear thinking about causality in the natural world a challenge. ↩