Against Empathy by Paul Bloom (Book Review)

I first heard Paul Bloom’s contrarian arguments against the intrinsic moral value of empathy on Sam Harris’ podcast about a year ago. Within an hour I was sold on the idea that this a priori unassailable virtue was in need of a dressing down. I put the book on my reading wish list and someone in my family was empathic enough about my prosaic interests to have it appear under the Christmas tree this year. While Against Empathy is only around 250 pages, it lays out its case succinctly and effectively. By the end of the book the reader will likely feel the need to reassess the value of empathy, or at a minimum think that empathy, as Bloom defines it, is not the moral panacea that it is often presented as. I emphasize that Dr. Bloom stresses a certain definition because he rightly points out that in common parlance the word has come to be synonymous with many concepts, such as morality, kindness, or the ability to feel another person’s pain - concepts which can be independent of each other depending on the context. The key distinction we are presented with is the difference between cognitive empathy and emotional empathy, which is the the difference between understanding versus experiencing the emotions and desires of another conscious agent. In Bloom’s account the latter empathy, now referred to as just “empathy”,[1] leads to a great many problems.

Before outlining what these problems are, it is worth considering the argument that cognitive empathy is not really possible without emotional empathy. Consider three examples as to why this must be wrong. Case #1: A colleague at the office comes by your cubicle and asks if you want to give some money for a employee in your organization who you only briefly met but who was recently diagnosed with cancer. You think it would be nice for them to feel support from the office without even imagining their situation. You give $20 dollars. Case #2: Your child wakes you up in the middle of the night and says there is a monster in the closet. While you are quite sure monsters do not exist, you perform a ritual of getting a flashlight, making sure the coast is clear and then tucking them back into bed. You are motivated by a concern for your child’s mental health without ever actually experiencing their fear. Case #3: My cell phone bleeps a warning message that my pattern of activity and heart rate are consistent with an elevated level of stress. You realize that your phone App seems better at noticing your moods than you do. What these three cases highlight is that it is quite easy to understand a person’s state of mind without ever experiencing their emotions.[2]

So while it may not be necessary to feel someone else’s emotions in order to understand them, it is probably helpful right? Most people hold this view, including Barack Obama:

The biggest deficit that we have in our society and in the world right now is an empathy deficit. We are in great need of people being able to stand in somebody else’s shoes and see the world through their eyes.

I think that the instinct to defend empathy comes from the many seemingly obvious examples where applying empathic understanding leads to better outcomes. This could range from: “I thought about how my friend would feel opening this gift, so it prompted me to get it for them” to “I thought what it would be like to be hungry so I decided to go volunteer at the soup kitchen”. The problem with this argument is that any heuristic can lead to a series of positive behaviors. For example, consider the practice of feeling jealous. I could easily come up with examples in my own life where jealously provided a motivation to a positive outcome, such as working harder or persisting in a difficult task in order to succeed. This does not make jealously a moral principle to live ones life by though; a fact that is obvious to most people because jealousy brings many pathologies with it too.

But what possible downside could there be with empathy? Bloom lays out two devastating and, in my view, undeniable points. First, empathy is biased. Second, non-empathic people can be highly moral, such as autistic individuals. The first point should be obvious: if empathy is the ability to step in someone else’s shoes, then the more similar their shoes are to mine, the easier it will be for me to step into them. This is why, as a Canadian, many of us gave to charities when the Fort McMurray wildfires broke out in Alberta. It was very easy for me to empathise with people living near cities I had stayed in, living lives similar to mine, and who looked a lot like me. In contrast, were a devastating wildfire to break out in California I would be able to express some sympathy, but I would be surprised if I opened my wallet. Or consider this, did you know that 250,000 people died of Malaria globally last year? How does this make you feel? Now consider that I lied, and actually 429,000 died according to the WHO. Do you feel 71.6% worse? The problem is that empathy does not scale, a point that was synically noted by Stalin: “When one dies, it is a tragedy. When a million die, it is a statistic”.

Throughout Against Empathy Bloom makes great use of Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Smith had already noticed the problem with empathy, even in a thoughtful and cosmopolitan man.

Let us suppose that the great and populous empire of China was suddenly swallowed up by an earthquake, and let us consider how a humane man in Europe—one with no sort of connection with China—would be affected when he heard about this dreadful calamity. I imagine that he would first strongly express his sorrow for the misfortune of that unhappy people, and would make many melancholy reflections on the precariousness of human life, and the pointlessness of all the labours of man, which could thus be annihilated in a moment. He might also, if he were given to this sort of thing, think about how this disaster might affect the commerce of Europe and the trade and business of the world in general. And when all this fine philosophy was over, and all these humane sentiments had been expressed, he would go about his business or his pleasure… with the same ease and tranquillity as if no such accident had happened.

But note:

… the most trivial ‘disaster’ that could befall him would disturb him more. If he was due to lose his little finger tomorrow, he wouldn’t sleep to-night; but he will snore contentedly over the ruin of a hundred million of his brethren, provided he never saw them; so the destruction of that immense multitude seems clearly to be of less concern to him than this paltry misfortune of his own.

Were Smith to have replaced your own finger with that of your child’s, I believe the point would still have held. The truth is that we will never be able to empathise with the suffering of strangers in the same way that we can with our own kin. This preference is an evolutionary imperative. Genes that promote behaviors which favour my own offspring, necessarily at the expense of others (as resources are finite), will have positive selection pressures. In fact this principal is true on a broader scale, namely that saving three of my siblings will preserve more of my genetic content than saving my own life. The principal of kin selection in evolutionary biology is how we are able to make sense of the behavior of social insects such as ants or bees and maintain the theory of evolution by Darwinian natural selection.[3]

I was recently watching the movie The Martian (which I quite enjoyed), and as the astronaut Mark Watney is making his life-saving attempt to reconnect with his ship, the event is being live-streamed across the globe, with crowds watching in the world’s major cities.[4] I found this scenario to be highly plausible. Would I go to watch an amazing feat of human survival in a public forum? Absolutely. Why? Because we can all imagine being Mark Watney, left behind on Mars by accident and making a last desperate attempt to reunite with his spaceship and crew.

We can all imagine being Mark Watney

Such examples are not confined to the realm of fiction. Certain disaster situations are irresistible to our human psychology due to empathy. I use the word irresistible not to make light of tragedies, but rather to point out that there is a certain morbid fascination we have with some extreme events. Like the proverbial pink elephant, we are unable to stop thinking about some things once they have been mentioned.

Empathy can be like the pink elephant

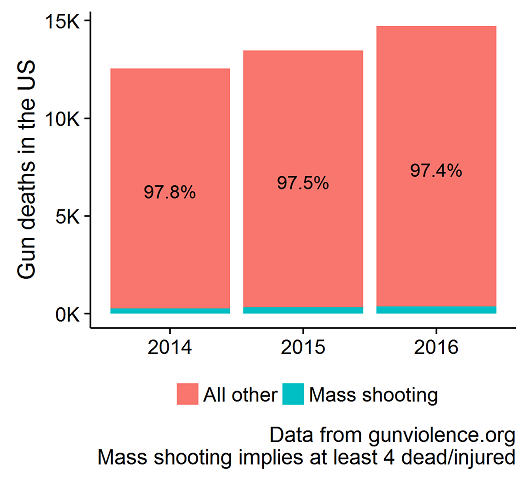

The first example Bloom makes note of in his book is the school shooting at Sandy Hook where twenty elementary students were killed by a deranged gunman. When the news first broke, many parents had the instinct to pull their kids out of school that day. A reaction that we can all relate to while at the same time understanding that it is not logical. In the aftermath, the city of Newtown was overwhelmed with gifts from people. Our ability to empathise with these sorts of tragedies skews our perception of risks. The US has a gun problem, but it does not have a mass shooting problem, if what you care about is the number of deaths. The figure below shows that mass shootings make up only a small fraction of gun homicides in the US.[5]

Figure: Empathy can skew our risk perception

Other examples of such events include the 33 miners that were rescued in Chile in 2010 or girl that fell down the well in Texas in 1989 which led to a national media circus used to excellent political effect by the Gipper himself: “… everybody in America became godmothers and godfathers of Jessica while this was going on.” We all understand why these events keep us glued to the TV, it is emotionally impossible not to feel the plight of some people in some circumstances.

The trajectory of this argument is clear: the current distribution of emotional concern is non-optimal. Instead of sending millions of dollars of plush toys to a small and wealthy suburb in Connecticut, gifts which may not even be wanted by the grieving citizens there, we should instead send money to the Against Malaria Foundation, one of the most cost-effective charities on the planet where it is estimated that every $7,500 in donations provides enough resources to prevent one premature death. There is as little certainty as there can be about the cost it takes to save a life, and these estimates come from the GiveWell foundation whose purpose is to measure the efficacy of such charitable programs. Another way to frame this problem is that empathy prevents us from equating the marginal supply of charitable donations to the marginal utility of charitable receipts, an argument that any economist would appreciate. In fact the author is quite generous to the dismal science:

I am going to say something nice about economists. This doesn’t come easy to me. As a professor, I can tell you that they are hardly the most popular individuals in a university, with their ridiculous salaries, fine suits, and repeated failures to warn us when the economy is about to go belly up. But their application of cold economic reasoning sometimes puts them on the side of the angels, as they work to be professionally immune to the sorts of prejudices and biases that most people are subject to. For instance, most economists believe in the merits of free trade, and this is in large part because, unlike politicians and many citizens, they refuse to see any principled difference between the lives of people in our country and the lives of people in others.

This rational approach to charity is at the heart of the Effective Altruism movement, to which Bloom makes positive noises about. He also allies himself with many of the points that Peter Singer has made.

Defenders of empathy may still be unmoved. Even if they agree that it would in principal be better to use compassion (i.e. cognitive empathy) over empathy (i.e. emotional empathy) in determining issues of public policy, this assumes that in the absence of empathy such emotions will be the default. Would a world without empathy have little to no charity or justice or morality? To iron man the point, Bloom notes that one of the defining characteristics of a psychopath is someone who is not able to experience empathy. However, psychopathy is always associated with other characteristics such as narcissism and lack of self control. Furthermore, a lack of empathy is not a sufficient condition for pathological behavior because individuals with autism or down syndrome also have low levels of empathy but can be extremely kind and moral.

The one area that Bloom leaves open to debate is the role for empathy outside of public policy. Would anyone want to be raised by parents who could never feel your emotions and treated you in a dispassionate and rational manner? One of the defining characteristics of intimate relationships is that we expect our partner to be partial towards us and treat us non-equally. I am myself unsure if it is ethically right to overweight those that we are most naturally empathic with in terms of friends and family. However, if the debate about the merits of empathy is reduced to this domain then the author of the book will be quite pleased with the results.

Footnotes

-

The former empathy, the cognitive one, can be thought of as social intelligence or the theory of mind. ↩

-

In fact I think all four permutations are possible: (i) emotional empathy without cognitive empathy (this would apply to narcissists: someone who feels what the sadness of others is like, but ends up feeling feeling sorry for himself), (ii) emotional empathy and cognitive empathy (I both feel your pain and understand why you have it), (iii) cognitive empathy without emotional empathy (I understand that you are sad without feeling it myself), and (iv) neither (rocks for example). ↩

-

J.B.S. Haldane a biologist who helped craft the Modern evolutionary synthesis is reported to have said to the question of whether he would lay down his life to save his brother, that he would not, but that he would do so to save two brothers or eight cousins. ↩

-

I say “live”, but the communication delay ranges from 3 to 21 minutes depending on the relative orbits of Earth and Mars. ↩

-

Another way to see the relative risks of gun homicide would be to note that if in the last three years there were fifteen times as many mass shootings, but half as many non-mass shootings, the US would have a lower homicide rate. ↩