Dialogue with Christian Bök and Anthony Etherin (Transcript)

Christian Bök is one of my favourite poets. I first became aware of his work with Eunoia, which is a critically-acclaimed collection of univocalic poems: each chapter uses only a single vowel. The work is a masterpiece and took Bök many years to write. Each chapter manages to focus on a theme. For example the “E” chapter is mainly about Helen of Troy. Not only does antilipogrammatic constrained writing demonstrate the flexibility and robustness of language it also reveals an otherwise hidden characteristic of vowels. The vowel “U” is shown to be crass, “E” is elegant, “I” is sharp, “O” is monastic, and “A” is delicious.

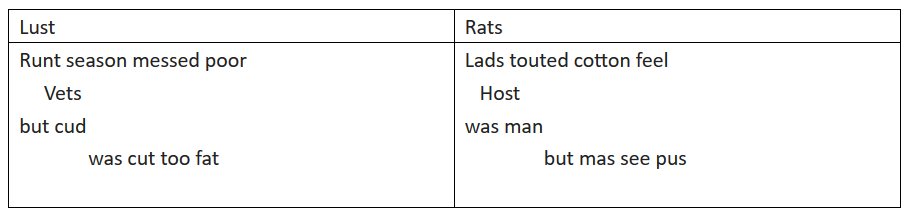

Bök’s newest and ongoing project is the Xenotext which seeks to encode a poem into DNA (under an amino acid to to letter mapping). Due to the complementary property of DNA, during transcription a second poem will be created in the mRNA (and possibly a protein in translation). The English part of the Xenotext poem therefore has an encipherment that maps every letter in the English alphabet to another letter to permit the genetic poem to maintain a meaning in both DNA and RNA.

Because Bök’s work is so interesting I decided to transcribe a podcast interview he had with Anthony Etherin on March 6th, 2020. Etherin is himself another well-known constrained poet and helped to found Penteract Press which publishes constrained poetry. The interview covers a wide range of topics including the origin of Bök becoming a poet, poetry’s failure to achieve commercial success, whether poets are deluded and naive, a significant discussion on the success of Rupi Kaur, how the internet and social media are changing poetry, and the philosophical approaches of the egotistical sublime and negative capability in poetry.

I’ve taken several editorial liberties in the transcript below including interpolating sentences, deleting repeated phrases, adding words where their meaning was evident, and deciding where to establish sentences. There are a few places where I have added links. As much as I like Bök he does seem to have a tendency for grandiloquence. For example he says I’ve explored eight trillion different worlds and in only one world does poetry exists. I know this statement to be erroneous as my partner was able to come up with a conceptual poem of the constrained type that Bök used in the Xenotext in a few hours.[1] I am confident that there are other mappings that would permit poems to emerge.

Nevertheless the conversation is an excellent elucidation into the avant-garde and constrained perspective. Bök argues, as he has elsewhere, that poetry’s failure to embrace and learn from science means that there are many avenues of poetic expression that have been left unexplored. After centuries of separation the fine arts and sciences no longer have a language by which to speak to each other. This is a shame, and hopefully Bök’s work will begin to start a reconciliation.

The Bök bio

AE: When did you first become interested in being a poet?

CB: I always knew that I would probably be a poet. I have an unusual origin story though. When I was about 4 years old, I was taken to a shopping mall at Christmas to meet with Santa Claus for the first time in order to ask for my very first Christmas gift. I didn’t know what to expect on this occasion, I just thought that it was quite miraculous that I could be escorted to this palace in a shopping mall and sit on the knee of a rotund guy in a red suit and he might grant me a wish. The very moment he asked me what I wanted for Christmas I said, somewhat spontaneously, a typewriter. I had of course no clue what a typewriter was, but I had heard that word, and I had asked for one promptly. Santa Claus, to his credit, attempted to talk me out of this particular wish and asked me whether or not I would prefer to have a teddy bear or a jet. Instead I got frustrated with Santa Claus and expressed my outrage that he wouldn’t offer me a typewriter.

To the credit of my working class parents they actually purchased a green plastic typewriter designed for children. I got this machine on Christmas day and I was taught very quickly how to use it. I promptly scrolled a sheet of paper in the platen and opened up my favourite book, an encyclopaedia of machines, that my dad had on his shelf. I was a weird kid who really enjoyed this strange book that showed exploded views of ordinary devices like toasters and fire extinguishers and had an explanation of them besides these diagrams. All I did was look at the glyphs on the page, find the shape on the keyboard and then hit the key. Even though I was illiterate, I’m only four years old, I would nevertheless sit there for hours typing out this encyclopaedia of machines. I would show each page to my mother and say “Look I’m a writer” because I had transcribed a page of written text from an encyclopaedia. I think that’s how I became a writer.

Now oddly enough, nearly two decades later I ended up in participating in the founding of an avant-garde literary movement in which we actually spend time retyping page from books and publishing them as works of poetry.[2] I think that the origins of my life as a poet begin when I was given that green plastic typewriter for Christmas and proceeded to pretend that I was a writer by typing out glyphs and marks from what was at the time my favourite book. When I was at university in my undergraduate days I took classes in writing and I was a very responsible as a student – I did everything that the teacher told me to do, and I wrote poetry that was merely okay. It was mediocre lyric poetry. I could get the occasional poem published, but at the time I recognized that I wasn’t going to be very good as poet. And it was only when I entered graduate school and learned something about the history of the avant-garde in poetry that I think I came to my full fruition as a burgeoning poet. I learned that I was attempting to become the type of poet I could be, not the kind of poet I should be. I think that that’s the nature of avant-garde poetry: to be the kind of poet you can be rather than the one you must be or have to be because someone tells you that’s how you have to be.

Being successful as a poet today

AE: You’ve said in the past that people become poets because they can’t be anything else.

CB: People who become poets get demoted to that job. You become a poet because you are incapable of becoming something else. If you actually had the capacity to be something else you would do that instead, because it would be an undoubtedly much more rewarding, more exciting profession that would grant you greater honour and more reward. In my experience, poets have found themselves in the position of “poet” in part because they feel they can’t do anything else. It becomes a kind of priestly calling that is the best reflection of their aptitudes because they have failed at everything else. I think that I became I poet in part because I failed at everything else.

AE: That’s quite negative isn’t it?

CB: I am being facetious I think. I’m remarking that there’s something about poetry that seems absurd as a choice of career. I’m always amazed that people think that they can make a productive life as a poet when there’s so much evidence to the contrary.

AE: But that’s why it’s amazing when someone actually does make money from poetry and more importantly acquires a fan base. And a fan base that isn’t just other poets… which you have done.

CB: My poetry made me money, yes. A very good supplementary income, and by most modern standards I’m among the most successful poets alive. But I’m far outclasses by the likes of Rupi Kaur who was most recently declared the poet of the decade; the poet of the 2010s. I’m very interested in her success in part because it’s so difficult to imagine any poet acquiring a small fortune. She must be a millionaire by now, she’s certainly sold millions of copies of her books. She’s at least outsold me, a fellow Canadian poet, by multiple orders of magnitude and I think that that’s a kind of avant-garde achievement because I think so few people have achieved it in the history of poetry. I’ve joked that Rupi Kaur is an avant-garde poet because unlike most poets she has made more money than you. She is a gigantic success compared to most of us, who are by comparison failures.

AE: It’s a remarkable story. There’s a poet selling millions of books. Much of her success if not all of it, is down to her use of social media, which is having a fascinating effect on poetry. I personally owe my own relatively very minor success to relentlessly posting poems of twitter. Although I don’t know to what extent I’m trying to become the constraint-based Rupi Kaur.

CB: There may be some truth to that! I wish that there were millions of dollars that could fall on you as a side effect of being so successful at social media. Certainly the advent of social media has altered the landscape for success. It’s now possible to route around many of the pathways to publication through the platforms available to everyone. For that reason I think it makes success a little more galling if not difficult because now everyone has access to the same tools to promote themselves, to achieve fame and glory, and there’s no excuse now for not being able to do so other than your own inability to find an audience.

AE: The poetry world seems to have a very uneasy relationship with social media. It’s amazing to see how many poets have Twitter accounts, but never tweet their poems. So they have an audience there, but no desire to take advantage of that.

CB: I think that there’s probably a split between those kinds of poets who are happy to publish their work on Twitter or Instagram and enjoy the creation of an audience in response to it. I think that if you have a growing audience of people who are constantly joining your team of followers and who are taking an interest in your work, there’s some incentive to satisfy demand by continually adding poetry to that forum. If however your work is relatively unrecognised, no matter what you do, you still have the same follower count, you don’t seem to be growing your audience quickly, I suspect that there is some anxiety about publishing. And I think that most people want to make sure that their work actually counts when it shows up in the world, they want to see that it’s had at least some modicum of impact. For some poets that might mean getting paid. They might want to see that there was some financial incentive that came with the publication.

I come from a clan of avant-garde poets who give everything for free. Some of us have gone onto much renown, in fact world-wide renown, and some of us have become best sellers and have earned money by selling poetry of all things. Nevertheless all of us have given it away for free. We’re probably the only movement in the history of the avant-garde that have actually made our entire oeuvre available online for anyone to read or download. I think that that’s unprecedented to make available work without mediation. That’s an important innovation in the distribution of poetry. But it hasn’t had much of an influence in the way people write poetry. Poets still write as though the internet and its social dynamics have not been invented. They still work as though this thing doesn’t exist. Whereas Rupi Kaur has figured out how to confabulate poetry in such a way that it would appeal to a broad audience within that milieu, with this platform, she has done something that provides permission for others. It would be lovely to recreate that formula. If you’re a young poet I could imagine you thinking this could be a wonderful way to start a career.

AE: Staying on the subject of Rupi Kaur. We know that social media has helped her find fame. That clearly doesn’t explain it all. Since not every poet with an Instagram account is famous. Is there some reason why the type of poetry she writes has become so popular that’s completely independent of the platform that people have seen it on?

CB: Let me put it this way. There’s lots of poets who have complained about the merits of her poetry. Perhaps I’m among those who might not find a great deal of interest in it for myself. It doesn’t appeal to my tastes necessarily. But I’m still impressed by the reach of it and the quantitative success of it. Because that’s difficult to achieve. Whatever formula she’s managed to figure out to acquire that kind of attention seems to me so far unreplicable for a lot of people. I would just simply say that if people are complaining about the merits of the poetry, you might want to ask yourself why your own work goes unread. Is it because your work is better or worse than hers? Is it because it fails to meet what might be regarded as a kind of poetic need among a potential readership? I think it’s harder now to complain about the success of others when everybody has access to this platform and can figure out how to use it for their own benefit in whatever way seems suitable to them. It’s one thing to complain about the success of others when there are lots of gatekeepers, when there is limited access to a limited number of poets. And publishers, when your audience is highly constrained. There’s no excuses now because of social media. If you haven’t figured out how to find favour with your audience it’s no longer the fault of the audience or the restrictions and constraints of publication and distribution, now it has a lot more to say about the merits of your own achievement.

AE: Whether we’re talking social media or traditional media, one undeniable fact is that poetry is hard to sell. And in many ways it’s not just neglected it’s not respected.

CB: Yes I love to quote a comment made by Charles Bernstein who is himself re-quoting someone else. My mentor Charles Bernstein once famously said that a blank sheet of paper with a poem written on it is worth less than a blank sheet of paper. As cynical as that joke is, I think it’s a funny thing to say if only because a blank sheet of paper has a tremendous amount of potential including laundry lists and shopping lists, all of which are probably more important or pragmatic for a sheet of paper than being used for a poem.

Again I’m surprised that there are poets who imagine that their contribution to culture will matter or that by simply writing poetry that it’s possible to change the world or become famous in part because of what you say on a sheet of paper. It’s evident that people would prefer to read stories and be given narratives about people rather than to hear the expressive thoughts and meditative thinking out loud of a person who has probably not accomplished much. That’s the weird thing that poets themselves are people who I think have sociologically accomplished very little, but nevertheless think they have much to say that would be an important contribution to culture. I’ve had many poets who say I want to be a poet because I really have an important insight. And yet I would say if you have something that is so important to communicate to the world, if it’s really so earth-shattering and news-worthy, then the proper venue is a press conference, not a poem. You put ideas and write down things in poems so that they can be forgotten or dismissed or discarded without much attention.

The audience for poetry is already pretty small and the means by which we measure for success are somewhat petty and tawdry. I’m considered a successful poet myself and yet I’ve only published over the course of my career something like 70K copies of my books. My entire oeuvre is outclassed by the sales of Rupi Kaur or any other bestselling author. And yet I’m considered an important personality because I’ve sold, by the normative standards poetry, a lot of books. And yet that’s not a lot of sales if you ask me. It’s a small town.

AE: But you’re the mayor.

CB: I just don’t think its a tremendous number of people.

AE: Going back to what you said about poets feeling they have much to say, we both agree I think that there is an absurdity in trying to spread a political message through such a neglected art form. But to give poets credit, I think most poets know this, and yet you still get a lot of political poetry. And there must be a reason for the prevalence for the political rhetoric in poems other than from delusions in its efficacy.

CB: We imagine that poetry is a place to go when you need to rejuvenate an otherwise dessicated language. A language that’s been abused by power. A language that has undergone travesties of its meaning. We look to poetry to resuscitate it, to reinvent it, to make it new again, to enliven it from an otherwise moribund state. Whether or not a poem can have much impact upon the world of thought and culture especially a time of turmoil seems to me unproven. Seamus Heaney once famously said no poem has ever stopped a tank. I think that that’s an insightful thing to say, but I also think that it neglects to imagine that no one has ever tried to stack the unsold backlist of Seamus Heaney in front of one. If you want to stop a tank all you have to do is stack enough books in front of one and there are a lot of books of poetry right? You could build a pretty big barricade of publications that go unsold. Poetry could probably stop a tank if it was put in one spot.

My own avant-garde attitudes are around the nature of form. The job of poet is to figure out what to do with language. It’s a kind of alien technology that we barely understand. Poets attempt to reverse engineer it for human purposes. Language is there to communicate things, to communicate ideas to each other, and yet it doesn’t do that very well. Or at the very least it does it in a cumbersome and inefficient way. Poetry seems to short-circuit some of the inefficiency. It does something unusual and strange and undermines or subverts these normative function of languages. In some sense I don’t know what poetry is for. I think every definition of poetry is correct because they all have something insightful to say about what poetry could be for. That’s why I don’t subscribe to any particular aesthetic attitude around the purposes of poetry. I’m sceptical around the political import of poetry. I think politics should be in the service of poetry rather than the other way around. It’s fashionable to think now that the job of the poem is to somehow take an activist agenda to say something that needs to be said in the face of power. I’m not so sure that that’s the primary function of poetry. Certainly it seems to have undermined the other functions to which poetry could be mobilized.

The poetic dichotomy

AE: Let’s talk about some of the different ways that poetry can be written. Some things that you and I have discussed in the past is the dichotomy between negative capability and the egotistical sublime. Would you mind briefly explaining these terms?

CB: These two ideas are important features in the romantic moment in the history of poetry. I think that most poets, especially young poets when they first start out, start from a romantic vantage that all of us, no matter what our interests as poets, probably begin from some sort of romantic standpoint. Who doesn’t want to be a romantic at heart in the world of poetry, especially if you’re young? But I do think that if you choose to be a poet you pick your weapons. Most poets are going the path of Wordsworth – they choose the egotistical sublime. They think of poetry as a kind of cognitive expression in which the poets speaks on their own behalf expressing their sentiments aloud, thinking out-loud, recollecting emotion and tranquillity, or finding some spontaneous outburst of feeling that is supposed to testify to the authenticity and sincerity of the poets personae. Certainly that trajectory has a long tradition throughout the history of poetry leading to all manner of confessional outpouring of feeling.

That’s not the only route that you can take from the romantic perspective. You could also take up the position of John Keats who suggested that the job of the poet is to adopt an attitude of negative capability not to express the self so much as to negate the self, and to allow forces to speak on their own behalf through the poet. This is the model of the poet as a kind of oracular visionary personality in the service to powers that are beyond them. That is the trajectory that leads through the wandering mazes of the avant-garde in the 20th century. You get two channels, two kinds of poetry that owe a debt to the history of romanticism, one of them is effectively lyrical in its attitudes and the other is effectively non-lyrical in its attitudes. And there are analogies in the histories of art. If you are artist after the 20th century you pick your weapons. You choose to follow in the footsteps of a Pablo Picasso and you adopt the lamp of expression. Or you choose Marcel Duchamp and you pick up the mirror instead. In the case of Pablo Picasso we’re indulging in the case of the egotistical sublime whereas in the case of Marcel Duchamp we’re dealing in the world of negative capability.

I’ve noted now that in the history of poetry, certainly recently, there is something in the egotistical sublime that wants to wipe out negative capabilities. That regards negative capability as treacherous to the self, that it forestalls activism; that true political sentiment can only be expressed through the authenticity and sincerity of the individual psyche, that there is nothing that can be activated in negative capability except a kind of self-serving vision of art for its own sake. In my case I picked up negative capability, that’s my weapon of choice, not the egotistical sublime. I’ve typically preferred poetry that doesn’t address the self, that doesn’t think out loud about itself, but instead performs other kinds of experiments – attempts to figure out what can be said. Something that’s not expressive so much as it’s generative. That the job of poetry might be to make things possible rather than to say things sincerely. I’ve probably oversimplified this dichotomy in the history of writing, but it’s one that characterizes the ongoing controversies in the world of poetry.

AE: Well let’s get to those controversies. Why does the egotistical sublime want to wipe out negative capability, and specifically why now?

CB: That’s a good question. There are many reasons that vary over the course of history. If you imagine that a poem’s job is to testify, then obviously being able to speak truth on behalf of an otherwise marginal experience probably has power and advantage. People want to know that their voice counts. That’s certainly implicit in the idea of the egotistical sublime. That every voice counts, that everyone speaks from a position of authority of their own experience, and that they can testify to it, and that there is value in confession. There’s an investment in self hood embodied in that, that thinks that truth can only be found through the avenues of sincerity, through the avenues of authentic expression.

There’s less of a notion that fundamentally language is something foreign to us, that we shouldn’t speak on our own behalf, that we shouldn’t adopt our own voice, because that’s what we already know. The job of poetry is actually to make discoveries, to generate possibilities to figure out what language could do if it was freed from the necessity to mean things, to say things that make sense. The job of a poem suddenly becomes to make music or to provide a lovely artefact that’s pretty to look at and hear, but says nothing. There’s some model of treachery in all of that because it doesn’t privilege experience. And experience is something that people value. They don’t want to see themselves denied. They equate that with being silenced or marginalized or bracketed. When if fact it could be that you have to get out of your own way; you may have to imagine being somebody else. What’s marvellous about literature is that people are obliged, at least in the best literature, to be something else, to imagine themselves in experiences that are not their own, to not write what they know.

In most creative writing classes we’re told to write what we know. I would caution poets not to do that if only because poets don’t know much. They’re not physicists or astronauts or business people, they’re not billionaires, they haven’t accomplished a lot, and yet they demand that we express what we know. It seems to me that if we were to examine the human condition very carefully, we might say that we know a lot when we actually don’t know very much. The job of a poem is to figure out what we could say rather than what we already know how to say. I’m not dissing William Wordsworth and his legacy, I think there is lots of cause to celebrate the lyric voice, it’s just that it’s the dominant one. And because it’s the dominant one it tends to suppress competing varieties of expression.

AE: Of course the best way we have of determining truth is science. And science does everything it possibly can to ignore the subjective voice. And the subjective voice of even scientists.

CB: I think that there is an element of the scientific at play in something like negative capability. If only because it aspires to what 19th century novelists would have appreciated as objectivity. They would have looked upon experimental literature at the time as an objective assessment of human relations. That required imagining yourself outside of yourself. It required thinking about the material relations between people and attempting empathically to create convincing psychological profiles that are not ourselves. In addition there’s an experimental and speculative dimension to that kind of work: we suppress ourselves on behalf of forces larger than ourselves in order to find out what they might want to say.

In that case I think there is a kind of experimental attitude or speculative attitude that we see in those moments of science when it daydreams. There’s something cool and objective in the artwork of Marcel Duchamp that has the kind of sinister clarity of a flat mirror, and it has no affect. It’s seems emotionless. It appeals to an intellectual attitude in art. By contrast if we look at a work by Pablo Picasso it’s infused with a kind of human warmth that is illuminating and reassuring in its sensible attitudes towards the world. It’s not something we’re supposed to greet as alien and strange, it’s something that greets us with recognition as a kind of wonderful expression of the human concerns. In the history of poetry there’s an attitude that is primarily humane in its understanding of language, and another in comparison, that is alien in its understanding of language. It simply greets the world with a detachment rather than an engagement.

Science and poetry

AE: I’m sure that most people listening will has some familiarity with the Xenotext project where you are actively combining science and art. I hope that’d you be happy talking about that for a little while, and also if you would say something about the current state of the relationship between science and poetry.

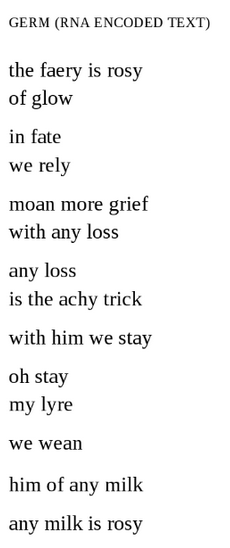

CB: The Xenotext is an ongoing experiment. I’ve been working on it since 2002 everyday. I have generated quite a lot of material as a side effect of this speculation. It requires me to write a short poem and then through process of encipherment I translate it into a sequence of genetic nucleotides and then with the assistance of a laboratory we build this gene and then implant it into the genome of a microbe replacing part of its genetic code with my poem. So the organism now becomes the living embodiment of this text. Moreover the organism can actually read this poem, it interprets this set of instructions for building a protein in its molecular structure, which is in itself an encipherment of a completely differently poem. So in effect I have engineered a bacterium so that it can not only become an archive for storing my poem, it also becomes a machine for writing a poem in response.

While I’ve managed to get this project to work successfully in a colony of microbes and I’m the first person of science to actually have gotten a microbe to do this, ideally I’d like to get this project to work properly in an un-killable bacterium capable of surviving in all kinds of hostile environments. An organism that can even survive in the vacuum of outer space, that can survive in nearly any kind of environment you can imagine. By putting my poem into this organism I would effectively be writing a book that could conceivably outlast terrestrial civilisation and might be on planet earth when the sun explodes. So in effect I’m trying to write a book that could last forever.

And of course I am responding to the technological-sociological circumstances of the 20th century. I think that of all cultural activities science is probably the most important, second only maybe to the economy, in human activity. Certainly our long-term survival as a species depends on our ability to get the science right, to solve problems with scientific detachment and an objective assessment of evidence and rational argument on behalf of these ideas that we learn. I think our ability to function within the universe really depends on our ability to get the science right. And yet despite the enormous advances in the history of science poetry does not spend much time thinking about it. And I lament that, for example, that there are no canonical poems in the history of literature for something as important as the moon landing. Probably the greatest technological achievement of our species, probably of any living thing in the history of life on the planet. It’s one of the most important evolutionary events of life of earth, and yet there are no epic poems about this event, nothing canonical, nothing even worth remembering 50 years after the staging of that expedition.

There’s something in the history of poetry that greets science with much suspicion. Ever since again the romantic era there’s a great deal of scepticism about the merits of science and I think some anxiety that science has a discourse of truth has displaced poetry from its prior supremacy. That we would count upon a poem to communicate the truth up until the Industrial Revolution. Most truths were probably conveyed in the form of poems, like for example, the Bible. We could go to religious texts to find what we would think of as a kind of cosmic truth about our condition and the Bible is a really beautiful book of poetry. But nowadays the poem does not speak much truth. Most poets prefer to write about their personal experience, their divorces, even though there are robots on the moon Titan taking photos of orange ethane lakes; the most surreal types of environments you could imagine, the most wondrous mythical milieu that goes ignored by poetry.

I don’t want to be one of those poets who ignores something so important. Lot’s of poets could address this particular discourse because not many do and it’s new un-ski’d snows. There’s lots of room for poets to make a contribution in that milieu. But it ranges very far from the catechism of most people’s literary training. You not only need to learn how to be a poet you need to learn how to understand the discourse of science and that requires a great deal of expertise. Nevertheless it’s possible to bridge these two divides. I’m a poet interested in brining together radically disparate discourses, put them into conversation with each other, and hope that there is something generative as a side effect it – that something unusual arises in these experiments. I had to learn how to do all of this genetic engineering and proteomic engineering myself. I taught myself a whole new battery of skills including computer programming and genetic engineering that have proven to be useful and interesting skill sets for a poet. The project is still ongoing. I’m doing my best to get it to work in the target organism, but so far I haven’t been able to hit all of the benchmarks for success. I’ve managed to hit many of them and have probably accomplished a lot more than many scientists and poets could do in my stead. Nevertheless I’m that I’ll find a pathway to success.

Teaching poetry

AE: Of course in addition to being a poet you teach poetry. How do you find younger poets respond to the idea of bringing in more rules to poetry or to the idea that poetry has its own objective rules. It occurs to me that younger poets in the grip of the egotistical sublime would be extremely resistant to the idea.

CB: Well I do think that creativity can be taught. I also think that there are a set of almost mechanical rules that if you follow will permit you to be competent as a poet. There’s in fact a handful of principles that always work, that are part of the tool kit of getting good at something. What’s unusual is that when you convey that, they imagine the purpose of a poem is to be authentic and sincere and they’re surprised that most of what makes a poem good has nothing to do with those attitudes. It’s possible to say something amazing and wonderful and beautiful that outclasses an inborn sentiment simply by doing something that is rule-bound and that functions almost mechanically. The students are often surprised that it’s possible to write something of merit by doing something that seems so automatic.

I’m saying this about expressive work and about lyrical poetry, I’m not saying this about avant-garde poetry which has its own set of procedural constraints and forms of weirdness that can be taught. For lyric poetry it’s actually possible to follow rules of expression that always work. Part of learning how to be a poet is mastering that tool kit as quickly as you can because it’s a short route to success. You get better by adopting these principles. And then of course you want your students to figure out how to apply them in a unique way. What I’ve learned about poetry in the course of teaching it for decades is that all poets write badly in exactly the same way. They all seem to make, collectively, the same kinds of mistakes. There’s a handful of recurrent errors that everybody who is terrible makes. But when people get good, when they overcome these handful of bad practices, when they get out of those terrible habits they all write well in their own unique way. They become fantastically wonderful in their own unique way. Everybody has an idiosyncratic pathway to success if they abandon these habits.

What I dislike about many contemporary creative writing programs is that they’ve become so formulaic in their attitudes to the workshop that they end up eroding some of the idiosyncrasies of style and produce a relatively homogeneous clan of lyric voices. If on the one hand we’re supposed to teach people to find their voice, it’s a cliché of pedagogy, and yet everybody who comes out of the programs sounds the same. The have many of the similar ticks, many conventional habits that are not necessarily poor, they’re just merely official. They become so normative that they are now boring, they don’t contribute to the idiosyncrasies and obliquenesses of a person’s form of expression.

The Christian Bök production function

AE: One question I want to ask everybody who comes on this podcast, is how to do you personally go about writing a poem. For example I would pick a topic, say for example the “moon”, then I would choose a constraint, or a set of constraints, for example I might decide to write a palindrome, and then I’d put those two things together and see where the language leads me. Just see what happens. Of course I appreciate that’s not how everybody else does it. I imagine that’s not how Rupi Kaur does it. We don’t know, I don’t imagine she’d ever come on this podcast. What do you do?

CB: Well you should invite Rupi Kaur I’d be curious to know how she writes. I would love to know how she composes her work. That would be very interesting because it’s a successful formula for reaching an audience. Every poem is an experiment. I don’t know what the outcome will be, and I don’t know what I’m saying in the course of saying it. I’m trying to find out what will happen in the course of writing the poem. I start with as series of experimental conditions. As you’ve said, I’ve got a topic, and I establish a series of constraints, of compositional rules. And you follow them out of curiosity, just to see what might happen as a side effect of doing this.

That’s often why I write a poem, I don’t know what I want to say, but I’m hopeful in the act of following these sets of rules I might say something interesting. And it’s a surprise. You hope that you will feel a sense of uncanniness by the outcome. I’ve never set out to write a poem that will have a particular effect. I haven’t said I’m going to write a sad poem today about this experience. That would be atypical, I don’t think I’ve really ever done that. Mostly I’ve come up with a really good idea for a procedure, for something I’m curious about, something that inspires speculation and interest, and I adopt it as a generative procedure. It’s not an expressive attitude towards work, I’m curious about what might happen as a side effect as adopting a principle and then I follow it’s composition to fruition and then I judge it’s result. If I’m surprised and feel amazed by it then it gets out to the world.

Sometimes I will give myself a challenge that I know will be difficult, I want to test my athleticism, my virtuosity as a poet, so I might set for myself a really difficult task that I know will be unprecedented and will be very difficult. And I hope that I can accomplish it as a stunt. To see if it is possible for language to be resilient enough, to be plastic enough to conform to this strange set of rules, which have been imposed upon it. I’ve tried to test my merits.

AE: Oh I’ve been there. It’s very exciting when you start, and then you get about half way through and you just want to kill yourself.

CB: Well I’ve written many poems where I’ve gotten about half-way through and not known yet what the outcome will be. Or whether it will be possible to finish a poem. I’ve gotten very far into the work with no hope that it might be actually be completable. I still don’t know if I can finish it. I have had occasions where I was writing a poem for someone and it was written to a whole variety of different constraints, and the person was asking what’s the poem about. And I said I don’t know. And she saying you’re down to the second last line, and I said I still don’t know what the poem is going to say. It’s like watching a flower germinate or unfold I don’t know what the actual bloom will look like until it’s fully unfolded and I can’t say with much trustworthiness how it will finish. I don’t even know if it can be finished, if it will actually complete. And she found that rather odd, that I wouldn’t know even though I was very close to finishing. And I still couldn’t figure out what I was doing. I said I wouldn’t know until the last word is on the page what it says.

AE: And this is true of your Xenotext poems, the Orpheus and Eurydice enciphered poems which are very important to your entire project, but you didn’t know if you could actually do it, if it was even possible to do it.

CB: Yes those two poems that I wrote for the Xenotext actually took about four years of effort to write. And I worked on no other poetry for four years. I worked on only those two little poems. The reason I spent so much time on them is that they are written to a whole variety of biochemical constraints that make saying something meaningful very difficult. And I’m proud of the work because I managed to discover them out of this rich potential: about eight trillion different possibilities I could explore, none of which generated anything but nonsense. And being able to find something meaningful in that welter of insensate statements, was a tonic for me, it was a big revelation to find these works. But I wouldn’t encourage other poets to do something so stupid to spend many many years working on two poems just to prove that it might be possible to do it. It wasn’t pleasant working on something for that long without much promise for success.

The reason I spent so much time on this was was that a lot of effort had already been invested and I had sunk a lot of money and time and effort already into the project and I couldn’t afford failure, I couldn’t afford giving up. I really wanted to be sure that the language was capable of doing it. And as it turns out, my faith in the language has been rewarded. Frequently at those moments when I thought for sure it was impossible, this particular task cannot happen, I’ve managed to make it happen. I’m proud of those achievements, when I felt that something was impossible but I accomplished it. I like to think I’m the poet does impossible things, who does something that no one else is willing to do because it’s already dismissed as simply impossible that it’s not conceivable that it can be done. Yet nevertheless I do it. And I hope that my career will testify to that virtuosity, and say look I’m the athlete. By contrast I look upon your own work with much wonderment. There’s a witchcraft in your work because I can see it would be extraordinarily difficult do it, and you do it with much aplomb. You’ve done it very quickly, faster than I could do it. That’s what amazes me about much of your work.

AE: Well thank you. But this is about you. So you have the encrypted poems.

CB: Sure I can read them aloud if you like?

The Xenotext explained

AE: Yes please, and could you also explain the rules behind the poems?

CB: Sure. When people ask me how these poems work, I say, imagine one of those cryptographic puzzles you see in a Sunday newspaper where you’re given a coded message, and if you analyse the letter patterns and letters frequencies of this meaningless message you could substitute for those letters alternate letters that produce a meaningful message. That you can decipher this encrypted message. And I would solve these puzzles as a young kid out of curiosity, they were just a form of entertainment, but I wondered at the time why the designer of the puzzles didn’t design them so that we would be given a meaningful message, something that made sense, but by analysing the letter patterns and frequencies we could substitute letters for those meaningful strings of letters and discover what the intended message was. It would be like encoding a meaningful message in yet another meaningful message. Most codes when we see them are meaningless messages the encipher a meaningful message. I used to imagine why wouldn’t you give me a meaningful message the encodes an alternative but equally meaningful message.

What I’ve done here is something analogous. To understand why it’s so difficult to do that imagine pairing off all the letters of the alphabet so that they are mutually encoded to each other. So that if you were to assign A to T, you would assign T to A, if you assign N to H, you assign to H to N, if you assign Y to E you assign E to Y, etc. Pair off the letters so they are mutually encoded. Now imagine that of all the possibilities you can pick one (there’s about 8 trillion different cyphers that conform to that constraint) such that if you write a poem and then substitute the letters in your poem with the letters from your cipher you produce another poem that also makes sense and is just as beautiful as the original. So that’s effectively what I’ve done, I’ve written a poem through a substitution cypher encodes yet another poem, and these two poems are mutually correlated, they refer to each other and are embedded within each other.

The letter pairing in the Xenotext

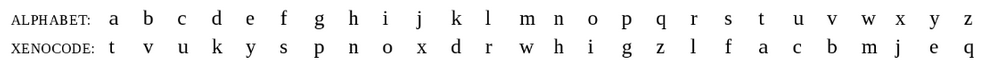

I had to learn some computer programming to design a piece of software that would permit me to explore these 8 trillion possibilities. I had to come up with potential vocabularies from these cyphers and figure out if it was possible to say mutually meaningful sentences and as it turns out, it’s not very easy. In fact it’s almost impossible. I spent years just trying to find even two phrases that would speak to each other sensibly. It just so happens that after four years working through vocabularies that were pretty small, I think the largest of the 8 trillion cyphers that I could find had about 700 words and it proved to be useless, I couldn’t make anything out it. So the particular poem I’m about to read is from a vocabulary that is only 120 words long, its not a very big vocabulary but it was sufficiently robust enough for me to be able to write these two poems. The first poem is entitled Orpheus, its the poem that’s written by me that gets enciphered into the bacterium.

Orpheus

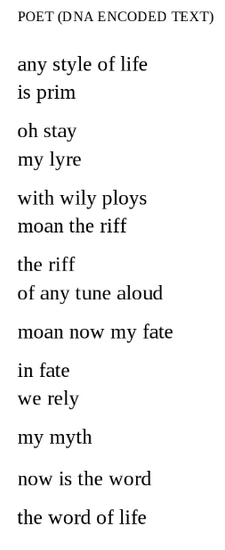

Now the organism can actually read this poem, it understands this poem as a set of genetic instruction and in response it builds a protein whose sequence of amino acids enciphers the following poem that I’ve nicknamed Eurydice, that’s in dialogue with the original. This is the poem that would be written by the organism in response to my text, and the poem Eurydice reads:

Eurydice

What’s unusual about these two poems is simply that they are the only ones that can be, I think, generated from this constraint. They conform to a style of poetry from the 15th-16th century in which a herd boy addresses a nymphette, and the nymphette rejects the advances of the herd boy. A kind of pastoral tradition of dialogue between two lovers.[3] Hence the nicknames Orpheus and Eurydice. There’s an infernal dimension to this work because they’re enciphered into an organism capable of surviving in all types of hellish environments. And the two works seem to allude to each other. The first is a kind of masculine statements about the artistic creation of life, the second is a kind of woebegone feminine statement about the artistic de-creation of life. I think there’s a bit of uncanniness in this discovery, it’s not immediately obvious that this would be the outcome of that constraint. I didn’t expect these poems to be the result of this particular exercise and yet out of the eight trillion worlds I explored these are the only poems that arise. In some sense that’s what makes them interesting an fragile to me as works of art. That they’re only poems that exist out of eight trillion possibilities. I’ve explored eight trillion different worlds and in only one world does poetry exists. There’s only one world where you might find life. It says something about the metaphorical fragility of our own existence in the cosmos. That there are trillions of potentially habitable worlds and yet only one of them seems to bear life as we know it.

AE: It’s always wonderful to discover these things. These happy coincidences that just jump out of the language. The uncanny is so important to constraint-based poetry and all experimental poetry.

CB: You’re hoping to solicit the uncanny. There has to be a kind of oracular dimension to the work, a spookiness if you like that arises as a side effect of it. That’s the kind of value in negative capability that it arrives at a kind of spookiness. That’s a totally different artistic value from authenticity or sincerity. Those are different. It’s not that it discounts those ones, it’s just that the standards of success are different, you know the poem is good because it instilled in you this sense of weirdness of the uncanny.

AE: And fun, it’s so much fun.

CB: Well you hope it’s fun. You also hope that you take pleasure in that experience. That it’s something which amuses you as a side effect.

AE: So finally, what are you working on now? The Xenotext is of course ongoing.

CB: It’s always the Xenotext. I have other subsidiary projects that are always on the go. They’re minor achievements, but the major task is still the Xenotext. And I’m hoping that I’ll be able to continue to accumulate resources necessary to continue doing the experiment. I’ve been fallow lately because I’ve not been able to re-secure access to a laboratory where for about 5-6 years a few years back I had a relatively consistent access to some expertise. That hasn’t been the case lately and as a consequence I haven’t been able to experiment with the constraint. I haven’t been able to sit in a laboratory and actually build the thing. Whereas as before I was able through trial and error do some play and work on this in the lab.

Nevertheless I’m hoping that I can transcend some of these difficulties and hit the benchmarks of success that would make me feel that I’ve done what I promised to do. Once that happens I can publish the remaining features of this work. I’ve already published half of it. Most of it is a kind of reflection upon the history of the precedents that inform my work. Things that have influenced this exercise. The forthcoming volume would be about the kind of futuristic implication of this work and how it might speak to the kind of science fiction horror of our future. I’m hoping that it will say something about our relationship to technology and contemplate our anxiety around our own extinction and the extinction of other species on the planet. At the moment when we have a big existential dilemma facing us. To me those are crucial concerns and the poetry that I care about seems to address them pretty directly. Science features pretty prominently in the work. Certainly invention and innovation and speculation feature prominently in the work that I like. It doesn’t seem to presume in advance how the world should be. It’s first priority is not so much political as it is aesthetic.

AE: A great sentiment to end on. As always it’s great to talk to you. I hope you’ll come back again.

CB: Yes of course I’d be delighted to carry on our conversation and do so via podcast. It was a great pleasure to be able to talk about my work. I hope that your listeners appreciate the merits of our conversation. Thanks a lot for letting me be your first speaker.

-

The mapping is: p:f, n:d, x:j, b:w, z:g, q:y, t:s, i:k, e:o, c:m, r:l, a:u, h:v. ↩

-

Bök is, I believe, referring to himself, Darren Wershler (a fellow Canadian), and Kenneth Goldsmith. ↩

-

See for example The Passionate Shepherd to His Love by Marlowe and Raleigh’s response in The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd. ↩