Beyond Hitler's Grasp by Michael Bar-Zohar (Book Review)

King Ferdinand I and Boris III of Bulgaria both had the misfortune of having to decide which alliance to support in a world war. Despite their different personalities and motivations both men decided to back the Germans. King Boris was a naturally shy man, and unlike his father he preferred wandering the countryside over issuing orders. In the 1930s Boris made the strategic decision to place Bulgaria within the Germany’s orbit. There were several reasons for this. Bulgaria was economically dependent on Germany (which accounted for half her trade) and her military was been supplied with German weapons. Most of the country’s generals were pro-German and many were Fascists. Boris feared that if he did not ally himself with the Nazis there may have been a coup. But Bulgaria could also not afford to antagonize the Soviets too much. Russia’s defeat of the Ottomans in 1878 was what led to the creation of the country. No Bulgarian would take up arms against their Slavic liberators. Partly because he hated conflict, Boris became adept at playing for time and being a conciliator.[1] Bulgaria’s policy leading up to WWII was preserve as much independence as possible within the German sphere of influence. Beyond Hitler’s Grasp tells the story of how Bulgaria managed to prevent the deportation of its Jewish citizens to the Nazi death camps. Bar-Zohar has written a masterful and well-researched account of the forces that prevented the destruction of Bulgarian Jewry. This is a story that needs to be told.

I was amazed to discover that the rescue of Bulgarian Jews was almost completely unknown. There were publications concerning the Danish rescue, the Italian rescue, about Raoul Wallenberg, Chiune Sugihara, and Oskar Schindler, but nothing about Bulgaria. I spoke about the Bulgarian rescue at several occasions. People would stand up and say: “This is a wonderful story, but it can’t be true. If it were true, we would have heard about it.” I thought that the unique story of the Bulgarian rescue, the largest and most dramatic rescue during World War II, deserved to be told.

In modern history being a Jew in Eastern Europe has not been an easy existence. Most of the Balkan Jewry descended from the Sephardi Jews who fled to the Ottoman empire after the Spanish Inquisition. As the Russian empire began to acquire Ottoman territory and Balkan nations obtained independence, new anti-Semitic forces began to appear with bloody consequences. Bulgaria’s history of anti-Semitism was relatively mild for the time and region. Tolerance of the Jews stretched as far back as the first King Boris I who embraced Christianity in 863 but chose not persecute the Jews and even absorbed many of their practices. Many of the question Boris I sent to Pope Nicholas were clearly influenced by Jewish ritual:

What day is the day of rest? What are the proper regulations for the offering of the first fruits? Which animals and poultry may be eaten? Is it wrong to eat the flesh of an animal that has not been slaughtered? Should funeral rites be performed for suicides? For how any days after giving birth is a woman forbidden to her husband?

In March 1941 Bulgaria officially committed itself to the Axis military alliance by signing the Tripartite Pact. German troops were now free to move through the country to attack Greece, and would do so in April 1941. Though Bulgaria’s military alliance with the Axis powers was constrained and her troops would not serve outside of the country’s expanded borders (which now included parts of Greece).[2] Amazingly Bulgaria would never be at war with the Soviet Union even after the Germans invaded in June 1941. It was the only militarily-aligned country where both the USSR and Nazi Germany had functioning embassies.

Bulgaria's prime minister signing the Tripartite Pact

The political situation became increasingly ominous for the the Jews of Bulgaria after the signing of the pact. Within the government there were a triumvirate of powerful anti-Semitic forces: the prime minister Bogdan Filov, the interior minister Petar Gabrovski, and Alexander Belev who led the Commissariat of Jewish Affairs (the KEV). All three men were thoroughly pro-German, hostile to Jewish interests, and in the case of the last two, part of the Bulgarian Fascist organization the Ratniks. Gabrovski had already sent Belev to Germany to study the Nuremberg laws and he helped draft Bulgarian’s equivalent legislation: The Law for the Defence of the Nation (ZNN). The ZNN stripped Bulgaria’s Jews of their economic and political freedoms. Jews were given a special curfew, banned from owning radios, required to surrender their bank accounts, and forced to relocate from Sofia – among other injustices. Despite making up a disproportionate number of soldiers and war heroes that had served in Bulgaria’s army during the Balkan and First World War, Jews were no longer allowed to serve in the combat units of the army and were impressed into labour units responsible for road building and other infrastructure projects. Despite the denigration of status, most of Bulgaria’s Jews remained proud of the country.

Jewish labour units in Bulgaria

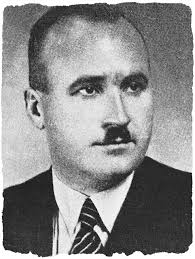

The first request for Bulgaria’s Jews to deported to German concentration camps came in February 1942. The Bulgarians dismissed the proposal as impractical and economically damaging. However the Bulgarian government accepted that any Jews living in country’s newly acquired territories of Macedonia and Thrace (in Greece) would not be protected. Official plans acknowledged that all 12,000 Jews that lived in the occupied territories would be deported by March 10th, 1943.[3] As the KEV began to meticulously plan the March deportations, Belev convinced Gabrovski to allow for an additional 8,000 Jews living in Bulgaria who were considered “trouble-makers” to be added to the list. As the date approached the modified Belev plan was leaked by numerous Bulgarians to leaders of the Jewish communities. Panic ensued. The first successful forces to coalesce occurred at Kyustendil on March 9th a day before the first deportations were to occur. A delegation of four Bulgarian gentiles led by the Dimitar Peshev left the city with haste to Sofia in order to convince the prime minister to put a stop to the deportation plan.[4] Unable to meet Filov, they instead met the interior minister who denied the existence of a deportation plan for Bulgaria’s Jews. Calling his bluff, Peshov demanded the minister call one of the district governors to see if they had received such orders. Gabrovski feigned surprise and put out an order to stop any deportations.

Dimitar Peshev helped prevent the March 10th deportations at the last minute

While Gabrovski was of course lying to Peshev and the delegation, the minister had already consulted with the King and Prime Minister and was ready to cancel the order. Gabrovski had no love for the Jews, but he was convinced that Bulgaria’s Jews could only be deported if the public remained unaware. He feared that public knowledge would lead to political backlash from the Palace, senior politicians, and a large share of the Bulgarian population who had no antagonism to their Jewish neighbours. Bar-Zohar’s meticulous research shows that when Gabrovski and Filov first heard word that a delegation from Kyustendil was on its way they conferred with the King and agreed to prepare an exit strategy. Gabrovski was ready to cancel the order before Peshev had even arrived. Everyone else remained in the dark. As news of impending deportations spread the country, the leadership of the Bulgarian church responded immediately. This was exemplified by the Bulgarian Patriarch (leader of the church) who was head-quartered in Plovdiv.

In the early morning, the news reached the head of the local church, Metropolitan Kyril. Strong-willed, ambitious, passionate and courageous, Kyril fearlessly and repeatedly had criticized the government’s policy towards the Jews. Back in 1938, he had written a brochure called “Faith and Resolution,” condemning anti-Semitism. A born leader and an independent man, he was among the leaders of the Bulgarian church’s opposition to the anti-Jewish policy; but in addition to signing the Saint Synod statements, he also issued his own letters of condemnation again that policy. He now acted immediately. He sent a telegram to King Boris, asking him to show mercy towards the Jews. He then went out into the streets. At the railway station a special train was to pick up the Jews. According to certain sources, Kyril threatened that if a train loaded with Jews tried to leave the city, he would lie across the rail road tracks… The rebellion by one of the heads of the Church caused great concern in Sofia. This was the first time in Bulgarian history that a prince of the Church had announced his refusal to obey the laws of the country.

Kyril responded immediately to help the Jews during the March deportation crisis

The courage and moral leadership displaced by the Bulgarian church presents an especially poignant contrast to the timorous approach taken by the Catholic church during the holocaust. While the deportations had been cancelled, Peshev pushed ahead and hoped to cement his gains by gathering 43 signatures from legislators who were part of ruling party in order to protest against the government’s Jewish policy. The tactic backfired and Filov was able to remove Peshev from his role of deputy speaker and reduce the influence of one of the most Jewish-friendly parliamentarians in the Sobranie.

Less than a month later, Boris was summoned to a meeting with Hitler at his Eagle’s Nest bunker in Berchtesgaden on April 1st. The Germans wanted to ensure that Bulgaria remained firmly aligned to the Axis cause. The country’s aborted deportation may have indicated to the Germans a weakening resolve. Hitler did not bring up the topic of the deportation with Boris and instead left the subject to be discussed in a private meeting with von Ribbentrop. The King to the Nazi foreign minister that his country had political constraints that prevented him from carrying out Germany’s deportation request. One was that the his countrymen were not intrinsically antagonistic to their “Spanish” Jews. Another being the need for Jewish labour units in the Bulgarian war economy. On April 13th Boris cemented the “labour” play as the final insurance policy against Jewish deportation: The Jews and the road construction became King Boris’ biggest bluff during the war. Oddly enough the one Nazi who did understand Boris’ motivation was the German ambassador in Sophia Heinz Beckerle.

The Bulgarian society doesn’t understand the real meaning of the Jewish question. Beside the few rich Jews in Bulgaria there are many poor people, who make their living as workers and artisans. Partly raised together with Greeks, Armenians, Turks, and Gypsies, the average Bulgarian doesn’t understand the meaning of the struggle against the Jews, the more so as the racial question is totally foreign to him. I am convinced that the Prime Minister and the entire Cabinet desire and aspire to a final and total solution of the Jewish question. But they are tied by the mentality of the Bulgarian people, that lacks the ideological enlightenment that we have. The Bulgarian doesn’t see in the Jews any flaws justifying taking special measures against them. The majority of the Bulgarian Jews belong to the working class, and unlike other workers, are often more diligent.

Despite the March cancellation and the King’s “labour” insurance policy in April, Belev would mount one more deportation attempt in May 1943. A political assassination carried out by a Jewish communist was used as a pretext for the need to bolster Bulgaria’s internal security. Belev drew up a meticulous plan that would be able to deport 16,000 Jews a month starting on June 1st. Once again though the plans were leaked and the Jewish leadership began to frantically lobby key influencers in the government. Metropolitan Stefan would lead the public protest throughout the month of May. He spoke directly to senior Bulgarian leaders during the Saint Kyril celebration day telling them to end Jewish persecution and also wrote and called the Palace on numerous occasions. Former ministers, writers, poets, and friends of the King (like Elin Pelin) volunteered to lobby the Palace to plead for clemency. One of the reasons Beyond Hitler’s Grasp is so compelling is that even though I knew that the deportations were going to somehow be cancelled I was completely at a loss as to how the impending tragedy was going to be avoided and I was desperate to finish reading the book to find out!

Stefan lead the Bulgarian Church's resistance to the deportations in May 1943

As the end of May approached the Jews and the their allies were becoming increasingly panicked. The King had not been seen for weeks and no responses were being heard from any government ministers. Stefan was even being threatened with prosecution. Belev once again believed he was on the verge of victory. But like the March 10th deportations, the Palace had already intervened behind the scenes. While Gabrovski had approved of Belev’s plan, he presented the King with two options: deportation of Bulgaria’s Jews to the Nazi concentration camps (plan A), or expulsion of the Sofia Jews to the provinces (plan B). The King categorically rejected plan A. Gabrovski was more cautious than Belev and was likely influenced by his correspondence with German architects of the Holocaust like Dennecker who at this point did not think the Bulgarians had the political will to carry out the act. The interior minister likely inserted this back-up option as a face saving exercise. On May 30th the government announced that the Jews would be forced onto the trains, but they would not be taken out of the country. They had been saved from destruction, but had lost most of the personal possessions and dignity.

As Russian forces began to drive the Germans back and the Allies landed in Normandy it became clear that Germany would be defeated. Aspects of the ZNN were rolled back throughout 1944 and the Soviets took control on the country in September 1944. Communist justice was mixed. Death sentences and severe punishments were given for many senior members of the Bulgarian government, civil service, and the Palace. The new communist government held numerous trials in a “People’s Court”, some of which focused on the crimes against the Jews. Peshev received a light sentence after a significant intervention from the Jewish community. Unfortunately no government official was held responsible for the deportation of the Macedonian and Thracian Jews. Belev never received a trial and was assumed to have escaped. However historical research shows that he was caught and executed by partisans as he tried to flee to either Serbia or Greece. In future years Communist Party history would credit their minimal role as being the decisive factor in saving the Jews and ignore the contributions that the Church, Palace, and Jewish community played in averting catastrophe. Such historical re-imaginings included planting in Todor Zhivkov into rallies he was never a part of.

Beyond Hitler’s Grasp one was one the best books I read this year. It is an excellent historical study of the power of both institutions and personalities. As Beckerle pointed out: the Prime Minister and the entire Cabinet desire and aspire to a final and total solution of the Jewish question. How could the Jews have survived such a powerful coalition of forces? The Jews of Bulgaria were completely assimilated, organized, and had numerous friends and sympathizers from the Pelin to Queen Giovanna. Much of the Bulgarian intellectual elite was especially proud of their constitution which guaranteed minority rights and political equality. Many were concerned that deportations would leave a “stain” on their country and threaten their aspirations of becoming an enlightened and modern polity. Because their opponents were fanatics but not madmen they were not willing to expend all of their political capital on the deportations. Bulgaria’s constitutional monarchy and the King’s personal popularity also ensured that the Palace would be able to check the prime minister and his cabinet.

The intellectuals, the academics, the writers, the doctors, the lawyers, launched a fierce crusade against the Law for the Defence of the Nation and deportation. It had no equal in any European country within the Nazi sphere of influence. The princes of the Church fought with total dedication against the anti-Jewish measures, confronting the government over and over again. The elder statesmen, the Communist Party, the opposition members of Parliament, struggled with tenacity and courage against the Jewish policy of the government

The Macedonian and Thracian Jews died because no one was interested, no one stoop up and fought for them. Thus, they became easy prey for the Holocaust machine… Their memory was erased, as if they had never lived on the sunny shores of the Aegean Sea and in the green valleys of turbulent Macedonia.

While Boris was not willing to do everything he could for the Jews, he still made four key decisions that proved critical.

- Reversing the policy allowing the non-Bulgarian Jews to be deported on March 9th after the last-minute intervention of the Peshev delegation prompted by the Kyustendil Jews.

- Denying von Ribbontrop his request that Bulgaria deport its Jews at the April 1st meeting in Germany.

- Pushing for all Jewish men to be put into labour units on April 13th.

- Informing Gabrovski that it would be option “B” and not “A” on May 20th.

Boris III -- the last King of Bulgaria

The fate of the Jews in Bulgaria presents an especially sad contrast to those of the other Balkan nations in 1944 when it had become clear that Axis powers would eventually be defeated. The Sztójay government took power in Hungary in March 1944 after a Nazi coup and began mass deportations. Pogroms occurred in Romania and a hundred-thousand Jews died in Romanian-operated death camps. After Mussolini’s regime collapsed, Italy’s Jews were rounded up. The Vatican was unable (or unwilling) to fully intervene to stop the atrocity. It should be noted that unlike the Catholic or Protestant churches, the Bulgarian Orthodox church reacted with complete moral clarity and openly threatened to disregard the government’s directives.

There is no doubt that in the entire history of the Holocaust, the Bulgarian church stood high above any other Pravoslav, Protestant or Catholic church, in her old and unyielding struggle to rescue the Jews.

After the war almost every Bulgarian Jew left the country to Israel between 1948 to 1952. Today Jews make up 0.03% of the Bulgarian population and there were more Jews in Plovdiv in 1800 than 2000. While the Bulgarian Jews who came to Israel were model citizens and Zionists, their community maintains a strong sense of pride and patriotism to their homeland. As Nora Madjar put it: “There are four types of Jews: Orthodox, religious, secular, and Bulgarian”.

-

Hitler dubbed Boris the “Fox” (which he meant as a complement) due to the King’s ability to leave a meeting on good terms while simultaneously having avoided the promise to do anything in specific. ↩

-

This arrangement would be similar to that of Finland’s whose troops would not leave the country’s pre-invasion territorial boundaries even after having pushed out Soviet forces. ↩

-

In fact every person in the newly occupied territories except Jews would be granted Bulgarian citizenship. ↩

-

Peshov would be one of twenty Bulgarians to be given the honorific title the “Righteous of Among Nations” by the Israeli state. ↩